(A longer version of this posting will be appearing in the journal of the California State Library, which houses the collected papers of Mr. Bernick).

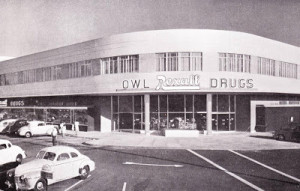

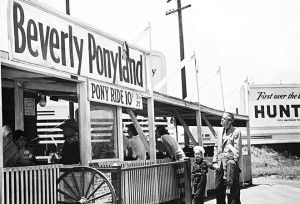

Over the past few months, I have been researching the job world in 1950s California for an essay in our California State Library journal. As part of the research, I set out to track the employment of adults on the street that I grew up on: the 8400 block of Fourth Street—between Orlando and La Cienega– in the Fairfax District of Los Angeles (neighborhood period photos included).

Most of us in our youth know little about the employment of adults in our neighborhood. When I started my research I had only vague idea of the occupations or work histories of the adults on this block. But I was able to find three of my former neighbors, all current Californians, who helped with research: Asa Baird, the retired winemaker in the Napa Valley, Peter Davison, the composer now living in Santa Monica, and Jeff Siegel, who is known to many F&H readers as the former horse racing analyst for the Los Angeles Times and other publications and commentator since 2002 on HRTV.

The conventional narrative of 1950s employment in California is one of job abundance and security. To a great extent this narrative is accurate. As EDD labor market analyst, Brandon Hooker notes, the unemployment rate in California for most of the 1950s was under 5%, and usually under 4%. Payroll job growth jumped from 3.4 million jobs in January 1951 to over 4.5 million by the end of 1957—the largest 7 year percentage gain the state has experienced in the post WWII period.

Further, in the period literature and popular culture, 1950s California is characterized by job security: employment with a single employer for a work life or at least a long period of time. Though we see little of Ward Cleaver’s work life in the six seasons of “Leave It to Beaver” (1957-1963), he and neighbor Fred Rutherford are said to be employed in secure positions with the local branch of a trust company. So too other adults on television during this period (“Father Knows Best”, “My Three Sons”) are in secure white collar positions. While there is little data on job stability in 1950s California, social histories of the period similarly portray forms of long term, stable employment.

Further, in the period literature and popular culture, 1950s California is characterized by job security: employment with a single employer for a work life or at least a long period of time. Though we see little of Ward Cleaver’s work life in the six seasons of “Leave It to Beaver” (1957-1963), he and neighbor Fred Rutherford are said to be employed in secure positions with the local branch of a trust company. So too other adults on television during this period (“Father Knows Best”, “My Three Sons”) are in secure white collar positions. While there is little data on job stability in 1950s California, social histories of the period similarly portray forms of long term, stable employment.

Yet, as is usually the case with narratives of employment, there is greater complexity. My one block of Fourth Street in the Fairfax district was not a cross sample of 1950s Los Angeles—its adult population was heavily Jewish, mainly second generation immigrants. However, the employment findings suggest the diversity of employment during this period.

I was able to obtain employment information on 9 adults. 8 of the 9 are men: the adult women on the block were not then in the paid work world—though they would be by the 1960s. Among the 9 adults, only 2 were employed throughout the 1950s in a long term employment situation with a single, large employer. The rest were self-employed or in small businesses.

I was able to obtain employment information on 9 adults. 8 of the 9 are men: the adult women on the block were not then in the paid work world—though they would be by the 1960s. Among the 9 adults, only 2 were employed throughout the 1950s in a long term employment situation with a single, large employer. The rest were self-employed or in small businesses.

1. Johnny Baird: A former boxer (he fought under the name “Kid Baird”); Self-employed through the 1950s as a produce/meat middleman.

2. Sidney Davison: A college graduate from New York who came to Los Angeles in 1930 and for the next two decades was a Communist Party organizer—sometimes operating under the name “Sydney Martin”. After the Party declined in the late 1940s and early 1950s, he found employment for a few years in the early 1950s in a meat packing factory, and in 1955 purchased and subsequently operated a Laundromat in Venice. In the 1960s he became chief purchasing agent of a company producing aluminum sliding doors in North Hollywood.

3. Manny Stevens: Studio musician and trumpet teacher.

4. Mr. Sherman: Plumber.

5. Isidore “Blackie” Samuels: Bar owner.

6. Polia Pillin: A ceramicist who worked out of her garage; she was not well-known in the 1950s but achieved notoriety in later decades, and her pottery and other art continue to sell today.

7. Mr. Zycher: The shipping manager for a clothing wholesaler in the 1950s, he would move from the block in the late 1950s and start his own small retail business.

8. Herb Siegel: A printer; one of the two adults with long term employment; worked for one employer, Reynolds and Reynolds, for over 35 years before retiring.

9. Sol Bernick: A faculty member at USC; the second of the two adults with one employer; stayed at USC from 1949 to 1986.

The degree of employment in entrepreneurial ventures and small businesses was surprising, though perhaps it shouldn’t have been. Most of what we “know” about 1950s California—whether it be race relations, or protest movements, or culture—proves when examined to be a simplification.

As I look back today, though, what is most striking is how wrong the government leaders, business leaders and commentators of the time in California were about our employment future. Nobody questioned that the job abundance would continue into the future. We were not many years removed from World War II (the assistant librarian in our local West Hollywood library had a concentration camp number on her arm). But the prevailing view: world wars and economic depressions were the past. In California, we could expect that the future would bring continued economic growth, driven by our dominant banks and financial institutions, aerospace and defense contractors, and agribusiness giants.

Of course, this perspective proved to be inaccurate on so many levels. What we took to be our economic birthright proved to be a small window in history, that closed by the mid-1970s.