Since Uber announced its downtown Oakland headquarters last Wednesday, a good deal of handwringing has followed about gentrification and threats to “Oakland values” and “Oakland’s soul”. So it is worth saying a few things about how tech firms in the past few years have been impacting urban form and urban economies in California.

Since Uber announced its downtown Oakland headquarters last Wednesday, a good deal of handwringing has followed about gentrification and threats to “Oakland values” and “Oakland’s soul”. So it is worth saying a few things about how tech firms in the past few years have been impacting urban form and urban economies in California.

At the start, let us note that even before the Uber announcement, Oakland has been developing a vibrant economy of internet commerce/social media firms. Susan Mernit of Live Work Oakland estimated in early 2014 more than 300 tech startups in Oakland, and the number has grown steadily since. Workplace incubators and accelerators either focused on tech or including tech entrepreneurs are multiplying: Impact Hub, 101 Broadway, The Port, Fruitvale Transit Village/Transmosis. Job training agencies specializing in tech training, especially for under-represented groups, are active, including the nationally-known Kapor Center (Freada Kapor Klein and Mitch Kapor) and Black Girls Code.

Uber, though, will bring the tech growth to another level. Aside from Oakland-grown Pandora, the City has lacked major tech employers. Uber will bring 2000-3000 new employees to downtown Oakland when it opens in the former Sears Department Store Building on Broadway and 20th. As importantly, it will bring other firms and entrepreneurs who seek to be near its engineering expertise and purchase of goods and services.

This is what has happened since 2011 following Twitter’s move to the mid-Market Street area in San Francisco. For forty years the City of San Francisco had been subsidizing redevelopment plans, seminars, community listening sessions and market analyses for this area between 6th and 12th on Market, with little or nothing to show. Then along came Twitter to locate in the largely-vacant Furniture Mart building at 1355 Market. Soon other tech firms, large and small, followed.

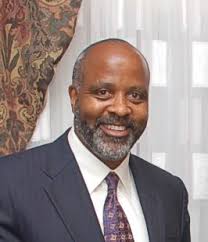

Alan Dones (pictured) is a third generation Oakland developer, whose father and grandfather were leaders in construction and development. He has patiently sought to revitalize areas of Oakland, investing his own money. He has done so through the many years in which major real estate investment has shied away from Oakland. He describes the Uber announcement as an event that should move the needle on real estate investment and business investment more generally.

Alan Dones (pictured) is a third generation Oakland developer, whose father and grandfather were leaders in construction and development. He has patiently sought to revitalize areas of Oakland, investing his own money. He has done so through the many years in which major real estate investment has shied away from Oakland. He describes the Uber announcement as an event that should move the needle on real estate investment and business investment more generally.

Further, for transit in the Bay Area the Uber move will be a positive. For the past few years, the BART planning staff, led by Van Menotti, has emphasized the reverse commute: the growth of job centers at BART as well as housing. Uber’s location next to the 19th Street BART station is one step in balancing the ridership flow, moving riders in both directions during the very crowded commute hours.

As detailed in a Forbes article published the day of the announcement, not all reaction was positive. Social media lit up with complaints about Uber’s entrance into Oakland. “The Uber-in-Oakland thing is probably great for Oakland ‘economy’, but really sucky for many people” read one, while another noted “Uber just announced its headquarters is moving to Oakland. Horrible news for Oakland renters.” The City Council President Lynette McElhaney warned that “This has got to be about two parts. The first part is Uber moving into Oakland. The second part is Oakland moving into Uber. And by that, I mean taking in our values and our ethos.”

There is no question that more will be heard about the new tech growth in Oakland and the type of city Oakland wants to be. All to the good. In California, we need ongoing discussion of what constitutes “progress” in our cities. The experiences across the Bay in San Francisco show that more and more building, “urban revitalization”, and higher and higher residential towers, may not be improving the quality of life, certainly not for the residents.

At the same time, there is a romanticizing of poverty in Oakland that often comes into the discussions of tech location. Anyone who has followed over the past two decades the attempts to generate more economic activity on the Broadway corridor in Oakland knows the many failed attempts. Here’s a recent shot of the east side of Broadway between 19th and 20th (captured on google maps here): a few non-descript and unwelcoming small office buildings, shuttered storefronts and marginal retail shops.

Finally, there is an element often missed in discussions of tech firms and urban economies: the ways that the young tech entrepreneurs are using the internet and social media to address longstanding social and economic issues in creative and effective ways. As noted a few years back in these pages (“Who Stole Bohemia“), tech entrepreneurs are finding new ways to fund small businesses and micro-busisinesses (Kiva, Kickstarter), to expand job placement, or higher education or lifetime learning.

Come to think of it, we might also include a ride-sharing firm that has used the internet to create new mobility options for individuals not able to drive, and for all of us.