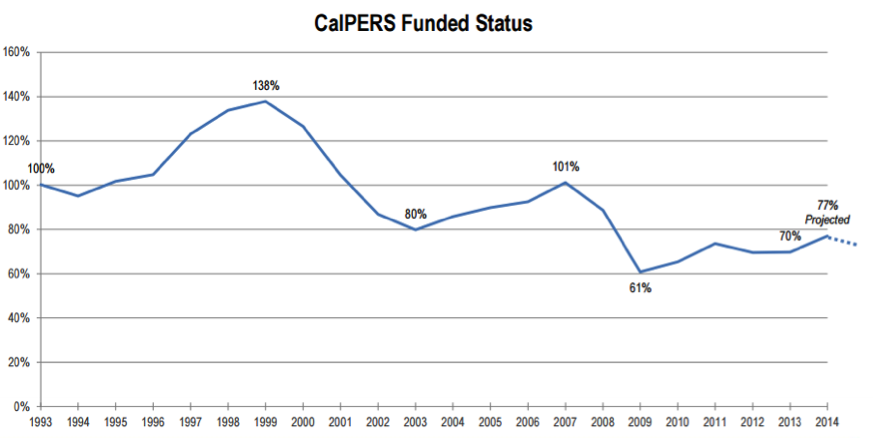

The biggest fiscal challenge facing California remains underfunded pensions. Ed Mendel’s Calpensions.com site featured a great chart showing how CalPERS’ current 75 percent level of funding has failed to repeat two previous restorations of value to above 100 percent. That article comes shortly after the fund reported its lowest gains since the Great Recession.

The biggest fiscal challenge facing California remains underfunded pensions. Ed Mendel’s Calpensions.com site featured a great chart showing how CalPERS’ current 75 percent level of funding has failed to repeat two previous restorations of value to above 100 percent. That article comes shortly after the fund reported its lowest gains since the Great Recession.

Why is this happening? I think there are two reasons.

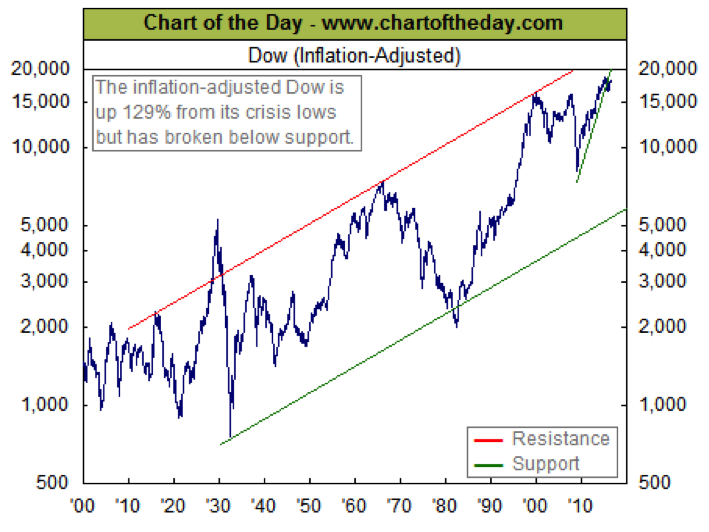

First, check out this new chart from the Chart of the Day site (to the left):

It shows, adjusted for inflation, the Dow Jones Industrial Average since 1900. The site notes that, since December 1999, “A decade and a half later, the inflation-adjusted Dow is up a mere 12%. That is not altogether an impressive performance considering that over 16 years have passed.”

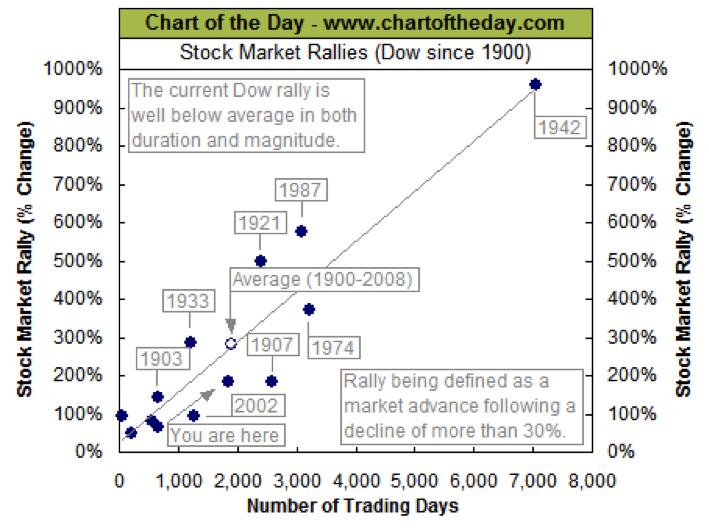

This is emphasized in another chart from two weeks ago:

It notes, “The current Dow rally is below average in both duration and magnitude.” The current tepid recovery is the dot in the lower left labeled, “You are here.” Notice the second and third best recoveries: 1987, after Reagan’s tax cut program; and 1921, after Harding’s post-World War I tax and budget cuts (described in “The Depression You Never Heard of: 1920-21”; the punch line is: because there was a boom instead.)

Of course, CalPERS invests in many other sectors of the economy than those tracked by the Dow. But the point is the Dow is one indicator that the whole U.S. economy is not performing well at all. At the recent conventions, not only Donald Trump and other Republicans decried the sluggish growth of recent years.

Hillary Clinton and other Democrats also noted, as she said in her acceptance speech, “We’re still facing deep-seated problems that developed long before the recession and have stayed with us through the recovery. I’ve gone around the country talking to working families. And I’ve heard from many who feel like the economy sure isn’t working for them. Some of you are frustrated—even furious. And you know what? You’re right. It’s not yet working the way it should.”

Let’s finally look at Mendel’s chart, which was provided by CalPERS:

It shows the funding level soared above 100 percent in the late 1990s, as the dot-com economy boomed. Then it slid below 100 percent, I believe, for two reasons: The dot-com economy went bust (shown as well in the first chart, above). But that also was the period of pension spiking, such as by SB 400 in 1999. I wrote numerous editorials in the Orange County Register at the time warning this would become a disaster. Which it now has.

CalPERS last inched above the 100 percent funding level in 2007. That was the height of the fake real-estate boom, which soon crashed into the Great Recession, slamming not just real estate in California, but everywhere; and taking down the stock markets as well. If you look at the chart, the last “normal” year before the boom, 2003, saw CalPERS funded at 80 percent. And since 2011, when the recovery began, it’s been at around 75 percent. That 75 percent to 80 percent funding during recoveries is the “new normal,” with the fund dipping even lower during recessions.

CalPERS also would help its investments if it would stop inhaling PC fumes, such as its ban on holding tobacco stocks. Reported the Wall Street Journal, CalPERS “missed out on up to about $3 billion in net investment …by not investing in tobacco shares.”

A commentator on the Calpension site also noted, “The primary reason pension funds can’t meet the 7.5% target is because of QE [quantitative easing]. QE has pushed interest rates to near zero making it impossible for pension funds to get returns on bonds. Back in 2000, you could load up on 10-year Treasuries all day yielding 6%. Add some dividend yielding stocks and making 7.5% was a walk in the park. If we had 6% rates on government bonds today pension funds would be in great shape.

“It seems to me that since a Federal policy – Quantitative Easing – is a large contributor to the pension shortfalls, the federal government should provide assistance in the form of payments to pensions to mitigate the problem they helped create.”

Actually, QE was the inflationary policy of the late 2000s. The commentator actually is referring to ZIRP – the zero interest rate policy, which indeed has hurt bonds. However, this is not a “federal policy,” but a Federal Reserve policy; and the Fed is supposed to be “independent,” at least on paper, and so far has resisted attempts by some in Congress, such as former Rep. Ron Paul, for a decent auditing. Moreover, ending ZIRP would mean U.S. taxpayers would have to pay much higher interest rates on the $19 trillion national debt. This is the problem that ensues when governments run up huge debts.

ZIRP is supposed to be a short-term Fed policy to shock the economy into recovery. But it now has lasted seven years. Japan’s central bank has pursued a similar policy since the late 1980s, causing three “lost decades.”

Although more sensible, Reaganomic-style economic growth policies by the Fed and the U.S. government obviously would help, the pension spiking remains the major reason CalPERS is underfunded. In the end, you know who will get hit for the expense: the taxpayers.