Everyone can see the federal shutdown is reducing some public services but California legislators are turning a blind eye to their state’s own shutdown. Public schools in Los Angeles, Oakland, San Francisco, San Diego, San Jose and other urban centers are providing just a fraction of full services, resulting in understaffed classrooms, underpaid teachers, and fewer arts, science, math, and other classroom offerings. One result is that the poor and minority students that make up a large share of those urban districts underperform poor and minority students in other states that spend much less per student.

The cause of the CA shutdown is exploding spending by school districts on pensions and other retirement costs. Because of that explosion, this year San Francisco will devote only 29 percent of its budget to certificated teacher salaries, LAUSD’s budget doesn’t qualify for a Positive Certification from the state and is headed towards diverting half of its budget from classrooms by 2031, Oakland is cutting services to erase a deficit, and San Diego is asking parents for advice about which of their kids’ services to cut. Even rich suburban districts in Marin County are shifting resources from classrooms because of rising retirement costs.

2018-19 Governor’s Budget

2018-19 Governor’s Budget

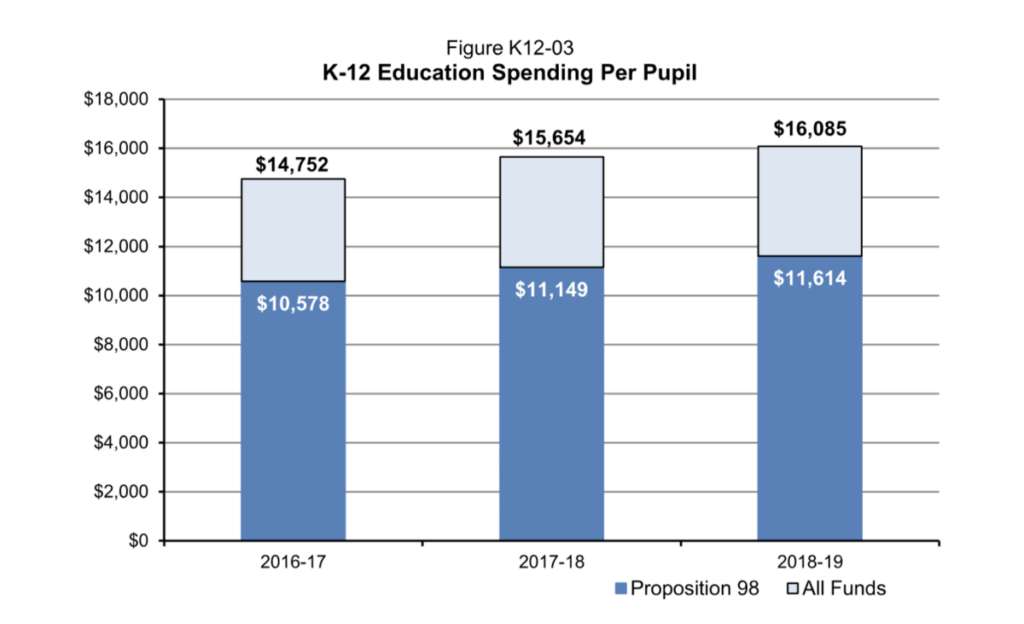

Normally California school districts hit rough financial waters during recessions but the reductions today are happening during an economic recovery and despite a bull market, 30 percent tax increase, 65% increase in spending over the last seven years, and spending per student of more than $16,000 projected in the next fiscal year. The problem is that an ever-larger share of that spending is being grabbed by fast-rising pension and other retirement costs before it can get to classrooms. Just imagine the consequences when the economic recovery takes a pause.

At his recent budget press conference Governor Brown expressed the view that the state had done its part for K-12 education by enacting the “Local Control Funding Formula” formula (see the 14 minute mark here). But that isn’t true. Local school boards cannot reform pensions without legislation approved by a majority of the legislature (62 members) and signed by the governor. Likewise, school boards cannot modify teacher tenure and dismissal rules without the approval of those 63 people in Sacramento. That’s because school districts operate in a straitjacket imposed by the state’s Education Code. One result is that school districts are unable to terminate the employment of next to none of the state’s 300,000 teachers. Needless to say, virtually every enterprise needs to terminate the employment of some number of employees each year. Not every employee is a fit for the job. But under current law, California public schools cannot do what every other enterprise — legislators and governors, corporations and unions, for-profits and non-profits — can do. The consequences of that straitjacket fall on innocent kids.

Perhaps it would help if more of California’s elected officials sent their children to urban public schools. Either way, those elected officials should recognize that they are responsible for an effective shutdown that impacts the most vulnerable students in their state. All it takes is 63 people in Sacramento to end that shutdown.