The Air Resources Board adopted its 2030 Scoping Plan late last year. The 2030 goal – a 40 percent reduction in greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions below 1990 levels – is mandated by state law. This is the state’s contribution to what the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change says the planet must achieve to avoid catastrophic climate change.

But, is an emissions reduction target the right goal?

UC Berkeley energy economist Severin Borenstein has weighed in on this question. His analysis merits our attention.

Borenstein identifies four interconnected state climate policy goals:

- Reducing California’s GHG emissions to a specific target.

- Demonstrating to the world that California can significantly reduce GHG emissions without significant economic cost.

- Creating new technology that lowers the cost of reducing GHGs globally.

- Reducing local pollutants, particularly in disadvantaged communities.

State law requires us to focus on the first goal. Politicians like to tout the second.

Borenstein says we should focus on the third.

First of all, climate change is a global emissions problem. California only produces about 1 percent of global emissions, so meeting the 2030 target really won’t make a difference to the climate.

Developing countries like China and India will produce most of the future emissions. So, Borenstein says, “If we don’t solve the problem in the developing world, we don’t solve the problem.”

He concludes, “The primary goal of California climate policy should be to invent and develop the technologies that can replace fossil fuels, allowing the poorer nations of the world to achieve low-carbon economic growth.”

Second, Borenstein points to a study he led that found that the cap and trade program, a major part of the state’s climate policy, likely has had little impact on emissions.

The governor and legislative leaders like to point out that market-based programs like cap and trade reduced emissions over the last decade while growing the economy.

But, Borenstein found that “…the impact of variation in economic growth on emissions is much greater than any predictable response to a price on emissions, at least to a price that is within the bounds of political acceptability.”

In other words, the great recession was the big factor in emissions reductions.

(For an example of how natural forces can affect emissions, consider the fact that 2016 emissions reductions from sources subject to cap and trade were largely due to increases in hydro-electric power after record rainfall.)

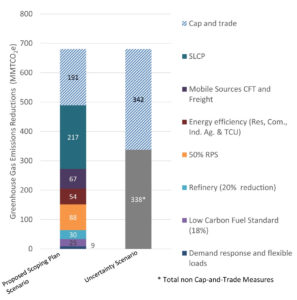

We may find out in the near future if emissions price increases under cap and trade will cause economic and political heartburn. This is because the 2030 Scoping Plan relies heavily on cap and trade as a backstop to achieve the target.

Indeed, a new report by the Brattle Group warns that, to meet our longer term target, emissions prices will need to rise substantially, which will lead to much higher energy costs.

That is, states the report, unless there is innovation in low-cost, clean-energy technology, particularly in transportation.

Technology innovation – the third goal.

Shifting to a focus on innovation becomes more compelling when you consider the following. First, global energy demand will likely increase by 30 percent between now and 2040. Much of this demand will be for renewables, including from global companies, which are committing to emission reductions as part of their risk strategies.

Second, energy innovation is shifting to Asia. A 2014 World Intellectual Property Organization study found that China and South Korea filed the most patents between 2006 and 2011 in biofuels, solar, and wind energy. The top 20 solar PV technology owners that year were based in Asia.

Third, manufacturing investment and job growth in California seriously lag behind the rest of the country.

With a focus on innovation, California would reap greater economic benefits making, using and selling advanced energy products and services to developing country markets.

The University of California has demonstrated what this focus can look like with its investment in Breakthrough Energy Ventures. The fund’s strategy is to link “cutting-edge, government-funded research to patient, risk-tolerant capital so that more clean energy innovations get to market faster.” This will allow UC to reap larger rewards from its innovation in energy storage, micro-grids, liquid fuels and other areas.

With a focus on innovation and entrepreneurship, we can be less obsessed with “bean counting” GHGs. Instead, we can count the new green technology companies spun out of our universities, the value of technology licenses, exports, and jobs created.

No doubt, California’s early climate leadership created momentum for new energy technology. But, it may be time to leave the heavy regulatory approach behind.

Consider Texas, where coal is losing out to wind, solar and natural gas. Smart energy deregulation and a modest renewable portfolio standard – not heavy regulation – were the major drivers here.

Climate change creates tremendous risks. Let’s not compound that risk with ineffective climate policy.