In 1993, novelist and California native Joan Didion traveled to the City of Lakewood in Southern California to report on its changing employment and culture. Her essay, “Trouble in Lakewood”, published 21 years ago this week, detailed a declining economy and troubled culture.

Lakewood was the largest of California’s suburbs built in the immediate post World War II period. As Ms. Didion describes, prior to World War II, the area that became Lakewood consisted of “several thousand acres of beans and sugar beets just inland from the Signal Hill oil field and across the road from the plant…that the federal government completed in 1941 for Donald Douglas.”

Beginning in 1949, three California developers, Mark Taper, Ben Weingart and Louis Boyar, started construction of their master planned city of 17,500 homes. They perfected techniques of mass housing production, so that these first 17,500 homes were built in less than three years.

Beginning in 1949, three California developers, Mark Taper, Ben Weingart and Louis Boyar, started construction of their master planned city of 17,500 homes. They perfected techniques of mass housing production, so that these first 17,500 homes were built in less than three years.

As Ms. Didion recounts, in the spring of 1950, thirty thousand people showed up for the first day that homes were put on the market. She goes on to describe the building and job generation: “Deals were closed on 611 houses the first week. One week saw construction started on 567. A new foundation was excavated every fifteen minutes. Cement trucks were lined up for a mile, waiting to move down the new blocks pouring foundations.”

Lakewood’s growth and employment was fueled by the defense spending linked to the growing Cold War. Decent paying jobs became plentiful at the nearby defense plants: Douglas, Hughes, and Rockwell. Added to these jobs were thousands of jobs at the Long Beach naval station and shipyard and the subcontractors who did business with these major employers.

By 1993, when Ms. Didion came to Lakewood, this defense and related aerospace industry was in sharp decline. The Rockwell plant in Lakewood closed in 1992 with a loss of 1000 jobs. Closures in the McDonnell Douglas plants throughout the area came to total 21,000 jobs—18,000 in the Lakewood area.

Ms. Didion’s essay portrayed an area not only of economic decline but also of cultural decline. Lakewood had created an artificial class of homeowners. When the Cold War ended this class was set adrift, economically and socially. Ms Didion came to Lakewood in 1993, seeing it as a transition time not only for the end of manufacturing, but for the end of a middle class built on this manufacturing.

Were these the last days of manufacturing in the Los Angeles-Long Beach region, including Lakewood? For the middle class?

Ms. Olga Hernandez is the EDD labor market specialist for the Los Angeles-Long Beach Metropolitan area and she forwards employment data for the area, spanning the period of 1990 to 2013. For this Metropolitan area, manufacturing employment stood at 813,400 jobs in 1990. By 2013, it was down to 366,500 jobs. Aerospace Product and Parts Manufacturing saw an even more dramatic decline: from 130,100 jobs in 1990 to 39,700 jobs in 2013.

Yet, manufacturing statewide is far from dead. Today, there are roughly 1,246,500 manufacturing jobs in California—down from over 1.8 million as recently as early 2000, but still a significant part of the state employment. In the Los Angeles/Long Beach/Glendale Metropolitan area, the loss of manufacturing jobs has been replaced by job growth in other sectors. The total jobs stood at 4,162,100 in the Metropolitan area in 1990 and is slightly higher at 4,198,400 in the latest EDD report.

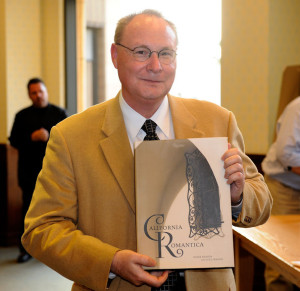

Further, Ms. Didion’s prediction regarding the demise of the artificial class of Lakewood homeowners has proved incorrect, as we hear from Lakewood native and historian Don Waldie. Waldie’s 1996 book, Holy Land, continues to be regarded as one of the most insightful of our postwar California narratives; and his on-going writing about the city and Southern California region show the rich life in Lakewood and other suburbs.

Further, Ms. Didion’s prediction regarding the demise of the artificial class of Lakewood homeowners has proved incorrect, as we hear from Lakewood native and historian Don Waldie. Waldie’s 1996 book, Holy Land, continues to be regarded as one of the most insightful of our postwar California narratives; and his on-going writing about the city and Southern California region show the rich life in Lakewood and other suburbs.

Reflecting on Lakewood today, Mr. Waldie notes that “Lakewood’s relatively large cohort of retired, long-time homeowners (because of their equity in a paid-off home) underpins the stability of Lakewood”. He adds that these long time homeowners as “habitual volunteers” bring an important social capital to the city’s wealth.

This may be the most important point of Lakewood’s experience, this July twenty-one years since Ms. Didion’s visit. The home ownership expansion of postwar California continues to bring social values, more than sixty years later.