California lawmakers are struggling to climb out of a deep hole. The gas tax that supports road repairs ranks among the highest in the country but the state has some of the worst roads in America.

A recent report from the state Senate said 68 percent of California roads are in poor or mediocre condition, the 44th worst record in the nation. It also said the cost for all of the unfunded repairs identified by state and local officials in the coming decade is about $135 billion.

State lawmakers are now meeting in a special session to find several billion dollars for the most urgent repairs, possibly with a higher gas tax.

If more money isn’t found, “these roads will disintegrate to the point where they’ll have to be rebuilt, which is very, very expensive,” said state Sen. Jim Beall (D-San Jose), co-chair of a special committee working on the issue. The state transportation department, Caltrans, estimates every dollar spent on preventive maintenance today averts as much as $10 in repairs later.

“When you start looking at data that says you’re paying the highest and receiving the lowest, that would mean that some analysis should be done to see where we can make improvements,” state Sen. John Moorlach (R-Costa Mesa) said at a hearing this summer.

If motorists do pay more in taxes and fees, they may be disappointed to hear that the money will do little to improve their biggest complaint about roads — traffic. The money under discussion is primarily to keep roads, bridges and related infrastructure like culverts from falling apart, not relieve traffic.

Transportation officials have identified about $57 billion in repairs needed for state roads in the coming decade in addition to about $78 billion needed for local roads, which are partly funded with state money.

Lawmakers in the special session, which was convened by the governor in June, are hoping to introduce a plan early next year that would fund at least a quarter of the total need. But reaching agreement has proved difficult.

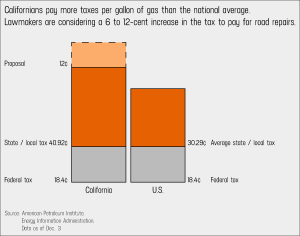

Beall has introduced a plan to raise $4.3 billion annually while costing the average motorist about $130 per year, including a 12-cent increase in gas taxes. Gov. Jerry Brown proposed a more modest plan that would raise $3.6 billion per year with an average annual cost to motorists of about $84, including six cents more in gas taxes.

For a variety of reasons, average gas prices in California are already about 25 percent higher than the nation. As of October 1, the price in California includes about 41 cents per gallon in state and local taxesand fees, the fifth highest rate in the nation, according to the American Petroleum Institute.

Republicans have been critical of tax increases, with some saying they would only be a final resort. Instead, Republican legislators have proposed to pay for the road repairs by redistributing existing state funds.

“At the end of the day, I think we’re going to have a discussion about revenue,” state Sen. Anthony Cannella (R-Ceres) said at a hearing in October. “But it’s got to be the last discussion.”

Any tax increase would require a two-thirds vote of both houses of the Legislature. Hence Democrats, who hold slightly less than two-thirds of the seats in both houses, would need Republican support. Lawmakers could also put a tax increase on the ballot, allowing voters to decide, but that would also require a two-thirds vote of both legislative chambers.

Lawmakers may also end up looking at a bond measure, said Rob Lapsley, president of the California Business Roundtable. In an election year, “it’s a whole lot easier to vote to put something on the ballot and let the people decide,” he said.

There are many reasons why the state’s transportation hole has grown over approximately the last 13 years. One is that the state hasn’t increased the gas tax since 1994, reflecting the political difficulty of tax hikes. Part of the state gas tax is also calculated as a percentage of the gas price, so when gas prices fall, so does the state’s revenue.

This year, the state gas tax fell by 6 cents per gallon. Overall, revenue from gas and diesel excise taxes has dropped from $6 billion to $4.9 billion over the last few years, Caltrans estimates.

Some of the money collected by the state is also distributed to local governments. So after revenues dropped this year, Los Angeles County is projected to receive $150 million in state gas tax revenues, $40 million less than it received a year earlier.

If the trend continues, “the county and other local agencies will be forced to significantly curtail ongoing operations and maintenance programs,” Kerjon Lee, a spokesman for Los Angeles County’s Department of Public Works, wrote in an email. The county is deferring $44 million in transportation improvements this fiscal year, Lee said.

In San Francisco, the paving budget has also been affected by the gas-tax revenue drop. “We had anticipated receiving approximately $14.6 million but now are expecting $6.1 million,” said Rachel Gordon, a spokeswoman for San Francisco Public Works, in an email. That translates, she said, to 56 fewer blocks repaved with that pot of revenue, as each block costs about $150,000.

In Stanislaus County, Public Works Director Matthew Machado said his department dropped plans to fix 85 miles of cracked and pitted roads. “I get super disappointed with our state legislators,” he said. “They know the problem. They have a solution at hand. They just can’t get together on the funding of it.”

Road funding in California is also challenged in several ways because of the state’s ambitious environmental policies.

Electric and fuel-efficient cars are proliferating, in accordance with environmental policies regarding clean air, fuel efficiency and climate change. Efficient cars use less gas and therefore pay less tax. All-electric cars pay no gas tax.

Lawmakers are considering a special $100 fee just for electric vehicles, as well as higher registration fees for all cars.

California also devotes a greater share of its transportation funds to public transit than most other states, said George Mazur, a Davis-based principal of the transportation planning firm Cambridge Systematics. And the California Environmental Quality Act raises the cost of construction by requiring environmental impact reports for road projects.

Caltrans has also come under fire for contributing to the state’s transportation funding hole. A report last year by the Legislative Analyst’s Office said a construction support program within Caltrans lacked adequate data to evaluate performance and it risked significant overstaffing, partly as a result of not cutting staff following the completion of big capital projects.

The governor wants to increase efficiency at the agency, and Republican legislators want to boost oversight of Caltrans to make sure it is using its money well.

But Caltrans Director Malcolm Dougherty said the legislative analyst’s report was off-base. “We are currently at the lowest staffing level we’ve been at in the capital program” in 20 years. Caltrans says the number of employees at the agency’s construction support program has decreased by more than 3,400 over the past eight years.

Dougherty says a major challenge for California is the sheer number of vehicles.

“What you have is a significantly greater wear and tear on your transportation system than you have in any other state,” he said. The large number of trucks, many traveling to and from ports, causes particular wear, he said.

State road budgets are also recovering from cuts made during the recession. Annual funding for the state’s largest road repair program — the State Highway Operation and Protection Program (SHOPP) — dropped from $2.6 billion in 2006 to $1.7 billion in 2010. The program currently has $2.3 billion in funding, less than one-third the amount that’s needed, officials say.

Emergency and safety projects come first in terms of spending priorities, along with fulfilling mandates and repairing bridges, said Dougherty. “Then we usually run out of money while we’re taking care of our roads, and we barely get to operational improvements,” he told a transportation roundtable in Fresno this summer.

California’s road system is a complex mix of funding and responsibilities shared by local, state and federal authorities. Virtually every road in California, except for private roads, can tap into funding from the state. Californians also pay a federal gas tax of about 18 cents per gallon, which helps pay for major highways and interstates as well as some local roads.

In Washington, President Obama signed a multi-year highway bill in December that could provide at least $5 billion annually to California in highway and transit funding.

Together, the federal, state and local needs in California are bad enough to rank the state among the worst road systems in the country.

Five of the 10 large urban areas with the greatest share of major roads in poor condition are in California, according to national rankings by TRIP, a Washington DC-based research group. San Francisco, Los Angeles and Concord top the list. California’s interstate highways are also among the worst in the country,according to the American Road and Transportation Builders Association, which uses federal data in its assessments.

Poor roads also have real consequences for motorists and businesses. A study from TRIP estimated that in San Francisco and Los Angeles, vehicle owners pay over $1,000 per year in maintenance and related costs due to poor roads — the most among large cities in the nation. Concord is third at around $950.

Hitting a pothole can mean blown tires, bent rims and damaged suspension — a problem that Douglas Marshall, owner of Autotrends Body Shop in Oakland, is all too familiar with.

Over the summer, his truck sustained damage to tires from hitting potholes, and his car bent a rim going over a pothole on Interstate 580. Recently, he said, a customer with a Mercedes came in with damaged suspension and wheels from a pothole. Potholes, Marshall said, “can be a hazard that can actually wind up hurting somebody.”

The roads are bad enough in California that state business organizations joined a broader coalition this summer urging a solution that could include higher taxes and fees, though the coalition wants to make sure existing road-related fees are also used for repairs and accountability is increased.

“Damage to vehicles from potholes, uneven pavement, and road debris produces higher repair costs (and insurance costs), but putting a vehicle in the shop can also mean delayed deliveries and order backups,” Lapsley, of the California Business Roundtable, said in an email.

Problems like that could be much worse this winter if a predicted El Niño-driven weather system brings heavy storms.

“If more rain does fall out of the sky, those roads will deteriorate that much faster, because water is the number one enemy of any road,” said public works director Machado as he drove along cracked, bumpy roads in Stanislaus County. “It will blow roads up.”

Cross-posted at CalMatters.