“The best things in life are free, but sooner or later the government will find a way to tax them.” – Anonymous

The most recent Public Policy Institute of California (PPIC) poll shows that a majority of likely voters backs Proposition 55 on the November 8th ballot. Proposition 55, the “Tax Extension to Fund Education and Healthcare,” would extend by 12 years the temporary personal income tax increase on earnings over $250,000 enacted by Proposition 30 in 2012. Revenue would be allocated to public schools, community colleges, as well as healthcare (in certain years).

For many, the appeal of Proposition 55 comes from the fact that “the rich” bear the entire cost. This was by design, of course, as Proposition 55 does not extend Proposition 30’s temporary sales tax increase. Sales taxes are commonly known to be regressive in nature.

This design has allowed proponents to argue effectively that Proposition 55 is a good deal for most Californians, since low- and middle-income households would receive additional education and healthcare services at no cost to themselves.

And who wouldn’t vote for a free lunch?

But what if voters knew that Proposition 55 wasn’t costless to them after all? That is, would they still support the measure as strongly if they knew it would raise their sales taxes, despite all of the pronouncements to the contrary?

Because a sales tax hike is the logical consequence of Proposition 55.

How is this the case? Consider the following:

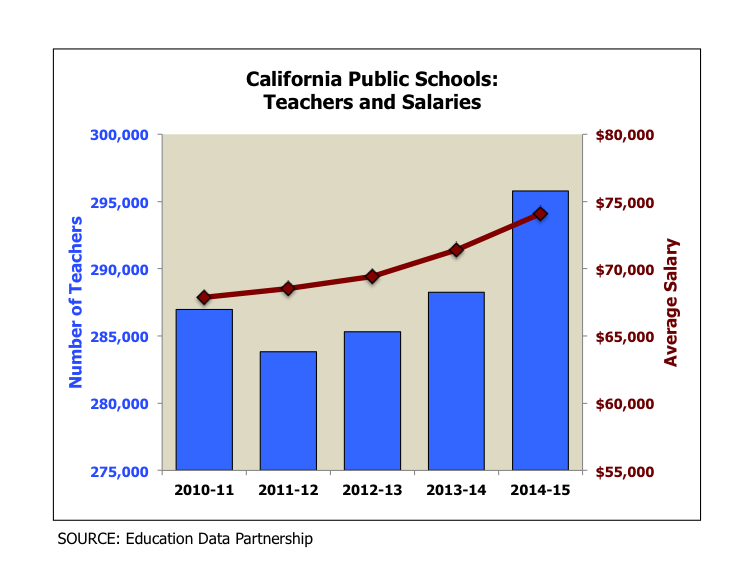

First, the Legislative Analyst’s Office estimates that Proposition 55 will generate between $4 and $9 billion a year, depending on the strength of the economy and stock market. (More on this in a minute.) Without the income tax extension, public schools would have to normalize their spending to fall in line with lower revenue levels. But with Proposition 55, public schools would base their spending plans upon tens of billions of dollars of additional revenue anticipated between now and 2030. Roughly 85 percent of spending for public schools goes to salaries and benefits, so recent trends suggest that the additional education revenue would go to increasing both teacher salaries and the number of teachers. (See figure below.)

Second, Jerry Brown raised the alarm in his 2016-17 Governor’s Budget that “another recession is inevitable and should be planned for,” highlighting the fact that our current seven-year economic expansion has already exceeded the average post-war expansion by about two years. Gov. Brown’s Department of Finance (DoF) modeled the impacts of a hypothetical recession of average magnitude occurring in 2017‐18. Under this scenario, DoF estimated that California’s “big three” taxes – the personal income, sales, and corporation taxes – would drop a total of $55 billion from the start of the recession through 2019-20, and that the state would be left with a $29 billion General Fund deficit by 2019-20.

Third, while no one is actually predicting a recession in 2017-18 and even though forecasting recessions is not an exact science, it’s uncontroversial to say that we’ll get one sometime in the next 12 years, before Proposition 55’s income tax hike expires. And when it happens and the state is confronted with massive budget shortfalls – due to our over-reliance on personal income taxes – education spending will be protected. That’s because spending on teacher salaries and benefits, unlike spending on supplies and services, is not easily cut if expected revenue doesn’t materialize. Moreover, the entire impetus behind Proposition 55 (and Proposition 30 before it) is to spare public schools from having to layoff teachers, slash educational programs and increase class sizes.

As the proponents of Proposition 55 are fond of saying, “California can’t go back!”

Finally, as Sacramento searches for stable revenue to solve its budget problems, it will turn to sales taxes as it has time and time again. In 2004, sales taxes were part of the “triple flip” compromise to cover nearly $15 billion in economic recovery bonds. In 2009, Californians saw a 1-cent increase in sales taxes to help deal with a $42 billion budget gap. And in 2012, sales taxes rose by a quarter-cent as part of Proposition 30 to address a $16 billion deficit.

In the end, it’s a predictable story: State government overextends itself on a volatile revenue source, an economic contraction leads to a budget crisis, and then Sacramento leans heavily on more stable revenue sources to close the gap.

Proposition 55 reminds me of the adage that the best things in life are free, but sooner or later the government will find a way to tax them. In this case, it will be out of necessity.

Dr. Justin L. Adams is the President and Chief Economist of Encina Advisors, LLC, a Davis-based economics research and analysis firm.