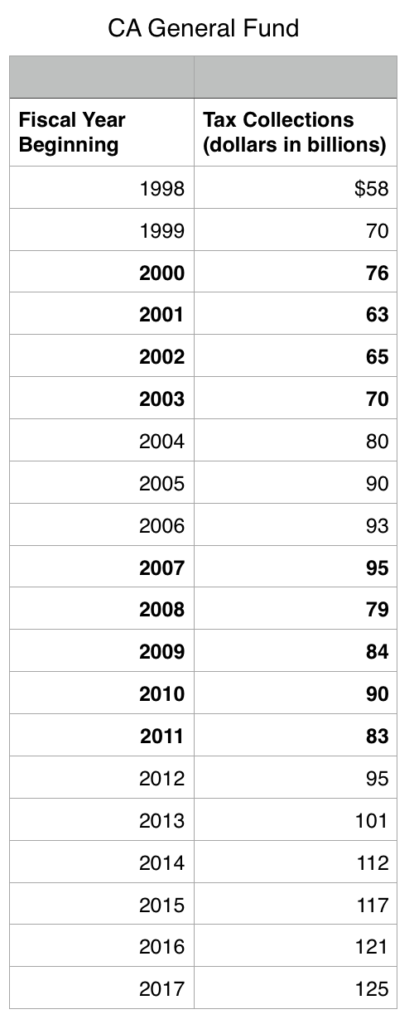

Take a look at California’s General Fund revenues over the last twenty years:

Schedule 2, 2017–18 Governor’s Revised Budget

Zero in on 2000-03. Notice how revenues peaked at $76 billion in 2000 and then fell below that level for three years. Aggregate revenues over those three years fell $30 billion short of the revenues the state would’ve collected had they continued at the 2000 level. Because Governor Gray Davis and the legislature had awarded big compensation increases and enacted new spending programs before the peak and the state had no Rainy Day Fund, after the peak they had to borrow, make cuts, and raise taxes.

Next, look at 2007–11. Notice how revenues peaked at $95 billion in 2007 and then fell below that level for four years. Aggregate revenues over those four years fell $45 billion short of the revenues the state would’ve collected had they continued at the 2007 level. Because Governor Arnold Schwarzenegger and the legislature had boosted spending before the peak and the state had no Rainy Day Fund, after the peak they had to borrow, make cuts, and raise taxes.

After a peak, California’s revenues generally take years to re-reach that peak.

Now look at 2011–2017. California’s revenues have climbed from $83 billion to $125 billion. Governor Jerry Brown has awarded compensation increases to some state employees but generally he has been more fiscally conservative than Davis and Schwarzenegger and also got voters to approve a Rainy Day Fund. But the state will still be worse off after the next market peak. That’s because Brown and the legislature have not addressed core budget issues. As proof, consider these unfortunate facts: If revenues over the next three years follow the same path as 2001–2003, revenues would fall $50 billion short. If revenues over the next four years follow the same path as 2008–11, revenues would fall $60 billion short. The Rainy Day Fund is expected to have a balance of only $8.5 billion by 2018, a drop in those buckets. Even if the Rainy Day Fund were to reach its constitutional maximum, revenues would still fall $40–50 billion short.

Worse, since 2010 Brown and the legislature have presided over a doubling of the number of Californians entitled to Medi-Cal and the addition of $100 billion of unfunded retirement obligations. Those entitlements and obligations are senior to discretionary spending, which leverages the negative impact on UC, CSU, parks, courts, welfare, taxpayers and tuition payers of a fall-off in revenues.

Californians are more vulnerable than ever to bear markets.

Brown can’t fix California’s budget on his own. He should press legislators to attack core budget issues on three fronts:

- Disengage tax revenues from the stock market or establish a much larger Rainy Day Fund.

- Get value — ie,health! — for Medi-Cal spending that’s increasingly crowding out other services.

- Reduce pension and other post-employment costs that are crowding out classrooms, new teachers and other services.

Californians won’t be lucky forever.

Brown has had the good fortune of governing during a bull market:

S&P 500 Index

His luck may last until he leaves office in January 2019 but that won’t help his constituents, who will need public services long after that date. Brown should press the legislature to address core budget issues.