I get the impression the University of California workers who went on strike May 7 don’t know the half of the financial problems of which the UC system suffers.

According to the Los Angeles Times, more than 20,000 members of the American Federation of State, County and Municipal Employees “walked off their jobs,” including “custodians, gardeners, cooks, truck drivers, lab technicians and nurse aides.”

Among other things, the union is demanding “a multiyear contract with annual pay raises of 6 percent, no increase in healthcare premiums and continued full pension benefits at the retirement age of 60.” UC countered with 3 percent annual raises for four years, raising the retirement age “to 65 for new employees who choose a pension instead of a 401(k) plan” and $25 a month in increased health-care premiums.

The AFSCME strikers were joined Tuesday by 14,000 members of the California Nurses Association and 15,000 members of the University Professional & Technical Employees, such as pharmacists and physical therapists. That forced the rescheduling of “more than 12,000 surgeries, cancer treatments and appointments.”

I guess the Hippocratic Oath’s pledge to “First, do no harm,” isn’t so important these days. And because this is a government-run system, the strike may be a strong warning against single-payer and other proposed socialized medicine schemes. In the private sector, if one part goes on strike, you can turn to another part. But when government goes on strike, you’re stuck, perhaps even getting a date with the Grim Reaper.

One worker was quoted lamenting “her pay increases over two decades at UCLA have not kept up with rising rent.” Of course, that’s a complaint almost all California renters could make because the Legislature and recent governors have refused to adequately address the causes for the state’s low housing supply. Blame also goes to AFSCME and the other public employee unions who keep financing the campaigns of legislators who refuse to solve the state’s pressing problems, while doing the unions’ bidding on pay and other issues.

But the UC strikers do have a point that the system’s finances are not in good shape. Let me add a few more concerns to their litany of problems.

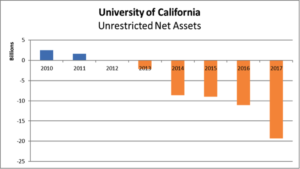

First, according to Gov. Jerry Brown’s January budget proposal, p.13, UC system retirement liabilities amount to $10.9 billion for pensions and $19.3 billion for health care – $30.2 billion total. Second, from the UC system’s 2017 Comprehensive Annual Financial Report, p. 36, the unrestricted net deficit is $19.3 billion. The U.C. system is upside down by nearly $20 billion! If the retiree health liability were added, it would double the deficit. Such is the joy of making financial promises that come due in the future.

Third, the Democratic-controlled state Legislature continues to reduce state funding of the UC system. Their fiscal priority is endorsed by Gov. Brown.

Fourth, as the Los Angeles Times reported in 2015, the UC system now employs more administrators than professors: “The number of those making at least $500,000 annually grew by 14 percent in the last year, to 445, and the system’s administrative ranks have swelled by 60 percent over the last decade – far outpacing tenure-track faculty.” As of that year, the system employed 10,539 administrators to 8,899 profs. Does anyone think a private-sector company could survive with more executives than production workers?

Tragically, these same administrators refuse to provide a 10-year strategic financial plan to provide a road map out of their fiscal morass.

And just a year ago, an audit by State Auditor Elaine M. Howle revealed severe financial mismanagement by UC President Janet Napolitano, including, “The Office of the President accumulated more than $175 million in restricted and discretionary reserves that it failed to disclose to the regents and created undisclosed budgets to spend those reserve funds.”

Fifth, this combined financial mismanagement obviously has increased tuition. Although an increase was avoided this year, the current resident tuition is $11,502, compared to just $2,896 in 1998. That’s a 297 percent increase in 20 years. By contrast, the Bureau of Labor Statistics’ CPI Inflation Calculator clocks overall price increases during that time at just 116 percent. Put another way, UC tuition increased at almost three times the inflation rate.

There are numerous tensions impacting the UC System. A defined-benefit pension plan prevents pay raises, as does the inability to constantly raise tuition. The solution resides with the state’s Democratic governor and Legislature.

More than 40 years of Democratic control have created this Gordian knot and something will snap soon. Perhaps the unions should realize the mess they have helped create. And voters should do the same.