(A modified version of an essay that appeared earlier this week in Forbes)

Today’s “future of work” discussions often are ahistorical—not recognizing America’s previous experiences with technological and industrial change. So as we approach Labor Day 2018, we can gain perspective on our present situation by briefly looking at an earlier period, the widespread plant closings and deindustrialization of the early 1980s, and how communities adapted and developed new economies.

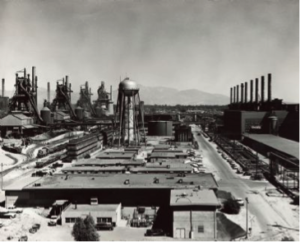

The plant closings that spread throughout the nation in the late 1970s and early 1980s, unprecedented in scope, were accompanied by specters of permanent high joblessness, a declining middle class, and an economy whose best days were in the past. In California, for example, more than 900 industrial facilities closed between 1980 and 1983, in automobile manufacturing, lumber and paper mills, food processing, steel. The mighty Kaiser steel plant in Fontana California, modernized just years earlier at a cost of $250 million, shut down in 1982-83, laying off 4500 workers. So too were shuttered the International Paper plant in Siskiyou County (600 workers), and the General Motors auto plant in Fremont (6500 workers).

The closings also brought a frenzy of state government action by 1982. Then Governor Jerry Brown’s Administration quickly established a “Reindustrialization” task force as well as a “Reinvestment” task force and a “California Economic Adjustment Team”. In the legislature, more than a dozen different bills were introduced, including ones on employee stock ownership plans, new government-backed funding, even a “Displaced Worker and Ridesharing” program (van service to connect laid-off workers to jobs).

Fast forward to Labor Day 2018, and what transpired over 36 years. The task forces, committees, and proposed legislation of that earlier time had little lasting impact. None of the schemes of new regional development banks, planning counsels, or additional government economic development staff, were implemented in California—and even the ridesharing for displaced workers was soon abandoned for lack of participants.

Yet, most of the communities affected by deindustrialization in California rebounded over the next decade, and in the most recent decade have achieved strong job creation numbers. The communities noted above of Fontana, Siskiyou, and Fremont, for example, all built new economies, with occupations and sectors not envisioned in 1982.

The closing in 1982-83 of the Kaiser Steel Plant (photo above) received national attention, a symbol of the decline of heavy manufacturing—the steelworker replacing Tom Joad as the symbol of profound economic dislocation, as journalist James Fallows noted at the time. The current president of the Fontana Chamber of Commerce, Phil Cothran, is a Fontana native and recalls his parents saying of the Kaiser plant at the time of its opening, “If this mill ever closes, Fontana will just dry up and blow away.” The city, located 45 miles east of Los Angeles, revolved around the plant employment, as well as employment at the nearby Eagle Mountain iron ore mining.

Yet, in the next years, Fontana did not “blow away”. For one, the steel plant came back to life, purchased by a partnership of Japanese and Brazilian interests, and reopened–albeit with a reduced workforce. Steel plant operations continue to the present on a section of the original 1800-acre site–with an auto racing speedway on another section.

More importantly for Fontana, new manufacturing firms were established, so that today the city of slightly more than 200,000 residents, is home to more than 400 manufacturing firms. “We make things here,” Cothran emphasizes, “manufacturing has come back strongly. We also have diversified the local economy with new jobs in health care, education, logistics, warehousing and construction.” Reg Javier, head of the Workforce and Economic Development activities for the County of San Bernardino, adds that “Fontana and the County are experiencing a boom in residential construction, driven by the high housing prices in nearby Los Angeles. Projections are for over 1.2 million additional residents in San Bernardino and nearby Riverside County within the next two decades.” The most recent unemployment rate for San Bernardino County is 4.4%, among the lowest rates since the current measurements started in 1976.

Fontana and the County have benefited from several factors beyond their influence, particularly the overall dynamism of the California economy (nearly 3 million payroll jobs added since early 2010) and the affordability of their housing and business operations, compared to other areas of the state. But also they have made their own good fortune. “Fontana’s approach has been ‘come sit down at the table and we’ll work things out’”, Cothran explains; highly pragmatic, responding to market signals, avoiding detailed and theoretical government planning, most of all seeking to give reign to private enterprise.

Similar practical, adaptive, market-based approaches have enabled other communities hit by plant closings in the early 1980s to rebound. The closing of the International Paper plant in Siskiyou County in 1981-82 was only one of numerous plant closings in rural northern California with the restructuring of the timber industry. Michael Cross, the executive director of the Northern Rural Training & Employment Consortium (NoRTEC), the job training and placement agency for the vast 11 county region, recalls that when he started in 1992, “Timber and paper plants were being shuttered, and we were scrambling to identify the job path ahead.”

But the timber industry did not die; it has carried on in the region in the 2000s, if, as with other heavy manufacturing with reduced workforces (the International Paper plant itself was re-opened by Roseburg Forrest Products and continues to the present). More broadly, new industries emerged in agriculture, including the recently-legalized cannabis production, forest management, tourism, and heath care. The region’s latest unemployment rates are at near all-time lows: 5.7% for Siskiyou County, 5.1% in nearby Butte County and 4.9% in nearby Shasta.

As Cross notes, the region’s job growth has benefited from the high quality of life for those who value the rural lifestyle and the increased ability of some professions to work remotely. Little of the growth, though, was foreseen thirty or forty years ago; it grew organically, as the communities adapted to markets, and, in their own ways, to globalization and technology. Government forestry and education departments are major employers, but main employment is through individual entrepreneurs and businesses.

Then there is the community of Fremont, in the south Bay Area, one of the best illustrations in the state of job growth that was not remotely foreseen in 1982. A few years after the General Motors plant in Fremont closed, it was revived as New United Motor Manufacturing (NUMMI) a joint venture of General Motors and Toyota. NUMMI, in turn, closed in 2010, only to be re-opened soon thereafter in its current role as the Tesla motor factory.

Heavy manufacturing, though it continues in Fremont, is only a part of the economy. The area has become a hub of tech research, development and production. It has become home to firms developing and producing semiconductor processing equipment, hard disk drives and storage equipment, solar panels: Lam Research., Boston Scientific, Seagate Magnetics, AXT. The latest unemployment rate for the area is 3.2%

The experiences of these three communities indicate not only the resiliency of economies, but also the importance of not trying to over-plan or direct the economy. A good amount of time is being spent in government, foundations and universities today trying to map out the job future. The experiences since the deindustrialization scares of the 1980s indicate that our ability to predict is limited—and predictions usually incorrect. Further, to restate, these experience show the importance for communities of being flexible, encouraging enterprise and entrepreneurship as widely as possible and among all populations, adapting as markets emerge.

And there is one further lesson, regarding the role of organized labor in the post-deindustrialization employment growth. Tim Rainey is the current director of the California Workforce Development Board and a former staff member of the California Labor Federation, where he worked on joint labor-management partnerships throughout the state.

Rainey explains, “Our efforts included getting involved in helping workers laid off to transition into new jobs. But Labor also had, and still has, a strong strategy of working in partnership with industrial businesses and other large businesses, who face increased competition globally, to restructure and thrive. We call those high road partnerships. We knew that the last thing workers needed was for a plant to close, since the prospects of re-employment at similar wages were usually difficult.”

Rainey and other Labor Fed staff traveled around the state, seeking ways to help California businesses compete, even if it meant leaner manufacturing approaches and fewer jobs in the short run. “It’s a long term strategy for good jobs. We worked in a range of fields: aerospace companies, mattress manufacturers, food processing. What is true across all industries is that the workers themselves often know plant operations best, want the business to succeed, and have good ideas for competitiveness.”

Let’s hold this last thought for Labor Day 2018.