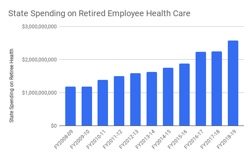

In December I became eligible for Medicare, the national health insurance program for people aged 65 and older. Medicare is fantastic — and fantastically cheap — insurance. But, believe it or not, if I was a retired California state employee, I would also be entitled to a state-provided health insurance subsidy that this fiscal year will cost the state $2.6 billion — more than double the cost ten years ago:

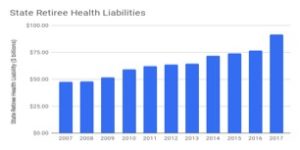

If you think Retiree Health costs are growing fast just because health costs are growing fast generally, you’d be wrong. Health costs for the state’s active employees grew at half the pace of Retiree Health spending. No, Retiree Health costs are growing fast because the state legislature and governor have created huge — and unnecessary — liabilities:

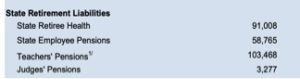

At $91 billion, Retiree Health obligations are now the state’s second largest retirement liability:

Even General Obligation Bonds, which require voter approval, are surpassed in size by the state’s Retiree Health obligations, which are created by elected officials without voter approval.

Because most of the state’s spending is determined by the constitution and entitlements and the legislature and governor tend to protect Corrections spending, the consequences of Retiree Health spending fall disproportionately on discretionary programs such as courts, UC and CSU. Looked at that way, the $2.6 billion spent on Retiree Health this year represents ~10 percent of discretionary spending. $2.6 billion is 35 percent more than the state will spend on courts, nearly 70 percent of the amounts the state will provide CSU and UC, and more than 85 percent of the expected cost of insuring undocumented seniors in California.

The state’s Retiree Health spending is not necessary. Retired employees aged 65 or older have federally-funded Medicare. Retired employees under the age of 65 can get federally-funded subsidies from the Affordable Care Act (Obamacare) through the state’s excellent health care exchange, Covered California. If necessary, lower-income retirees could still be selectively subsidized by the state.

Glendale shows the way. By transitioning retired employees to Medicare and Covered California, delinking the medical insurance premium rates paid by active and retired employees, and providing subsidies only to those who need them, the City of Glendale reduced its Retiree Health liabilities by >90 percent (see page vii of 2017 Glendale CAFR). Using the same math, the state could reduce liabilities by >$80 billion and save >$2 billion per year. Glendale provides answers to frequently-asked questions about its changes here.

There’s no reason for California to starve discretionary programs, squeeze current employees or charge taxpayers to provide unnecessary subsidies when generous federal subsidies are available. The state should end the practice of subsiding retired employee health care. In doing so it would also set an important example for California’s many school districts and local governments suffering from similar unnecessary liabilities.