The chorus is growing louder that an oil severance tax must be part of the budget solution. Proponents of the tax on extracting oil from the ground or from under the sea echo the same refrain that California is the only oil producing state that does not levy such a tax. What supporters of the tax fail to mention is that oil production is already heavily taxed in California. Adding an oil severance tax would zoom California oil producers to the top of the tax chart by a significant degree and that has consequences.

Oil companies in the Golden State pay corporate income taxes, property taxes and sales taxes on their business. Not all oil producing states assess all these taxes, nor are the tax rates the same as high income, high sales and high corporate tax California.

A year ago, the Law and Economics Consulting Group (LECG) was hired to project the results of a 9.9% severance tax proposed by Governor Arnold Schwarzenegger. Dr. Jose Alberro, an expert on petroleum and valuation and Dr. William Hamm, former state Legislative Analyst conducted the study. It is true that the sponsors of the study were members of the oil industry, but the authors noted they were given complete control of the report and that the report’s conclusions are the product of independent analysis. Anyone can challenge the report’s findings but the report makes some straight forward, common sense conclusions.

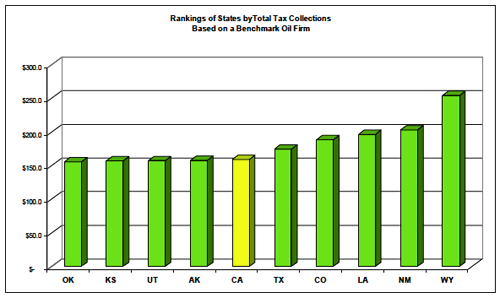

According to LEGC, taxes on California oil producers rank sixth of the top ten oil producing states as can be seen in the chart below.

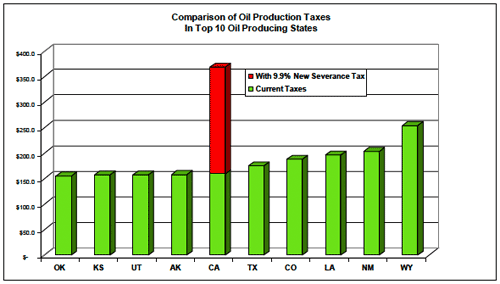

But, add an oil severance tax of 9.9%, which is the tax rate most often cited by the severance tax supporters, and California oil producers immediately jump to number one by a significant margin.

Raising the tax on oil producers has many consequences. The tax expense will likely be passed on to consumers at the pump. The cost of production may slow or eliminate some wells. That means Californians will have to import more oil. Jobs would be cut so the oil companies have the revenue to pay their tax bills.

It should also be noted that California oil production has dropped nearly 50-percent in the past 25 years and that California produces mostly heavy crude oil, which is more expensive to extract. Discouraging higher taxes may encourage some producers to cap their wells.

One proposal to establish an oil severance tax actually just amended its proposed tax rate upward to 12.5%. Assemblyman Alberto Torrico’s AB 656 also purports to have remedies to counter any attempt to increase costs at the pump for consumers.

This measure forbids oil companies from passing on the tax increase. If it is suspected that the companies have passed the cost along the bill says they will be “investigated.”

Let’s assume for a minute that it is even economically possible to prohibit passing on costs. Torrico figures the oil companies are rich enough to pay the new tax. While his bill attempts to exempt small producers, it will be more than big oil that will be caught in the tax trap. If oil companies cannot pass on the tax they will likely cut back on production or eliminate jobs. Suppliers to the oil companies from hardware to food services will also feel the effect.

There’s another interesting item in AB 656. Borrowing a trick from Congress, the bill exempts government from its provisions. The bill states that oil production owned by political subdivisions of the state are not subject to the tax. The idea that government gets a break that the private sector doesn’t is galling.

Besides being more competitive to sell its oil, the public sector does not have to worry about trimming back the work force to make ends meet.

Torrico’s bill also calls for the tax revenue to be deposited in a fund for higher education. Putting more mandates on the funds collected by the state is bad public policy and relying on what most agree is a diminishing resource is no way to fund an on-going expense like higher education. However, that is a discussion for another column.

If the oil severance tax idea were all about putting California on an even field with other states, then raising a severance tax would come with some proposed reductions in other taxes the companies pay. In fact, the opposite is occurring. With the various severance tax proposals that are circulating, if passed, California oil producers would be paying among the highest sales tax, corporation tax and severance tax.

And, it should be noted that some of the same people who support an oil severance tax also want to increase property taxes on commercial property.

The efforts to create a California oil severance tax is all about increasing revenue with little regard for the damage such a tax increase will do to the California economy.