This essay first appeared earlier this week in Zocalo Public Square.

California Used To Embody Stable, Middle-Class Living. It Was a Brief Interlude.

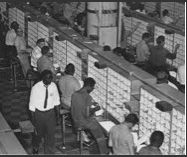

The photo below was taken at the Lockheed Aircraft Company Christmas Party in Burbank in 1950. The smiling Lockheed workers are receiving awards in honor of their fifth anniversaries at the company, awards that reflect the stability of regular pay benefits and employment.

From January 1951 through November 1957, the unemployment rate in California never exceeded 5 percent. For much of the time, it was under 4 percent. The number of nonfarm payroll jobs grew from 3,406,900 in January 1951 to 4,877,100 in December 1959. In the following decades, the abundance continued, with nonfarm payrolls growing from 4,882,400 in January 1960 to 7,027,900 in December 1969.

I grew up in Los Angeles during this time, and whenever I speak to classmates (John Burroughs Jr. High ’67, Fairfax High ’70) we marvel at how the job world has shifted. What happened to that California?

The post-World War II California economy was dominated by large private companies in aerospace, heavy manufacturing, finance, insurance, telecommunications, and rapidly expanding public sector entities—the U.S. Postal Service, the state employment/unemployment offices, the local governments, and school systems. Once hired into these private or public entities, in the absence of misconduct, a worker could expect long-term employment.

The histories of California of the 1950s and 1960s capture this phenomenon. The father of D.J. Waldie (Holy Land) worked for the Southern California Gas Company designing pipelines for 30 years. Waldie’s neighbors in Lakewood were employed in nearby Long Beach at the Douglas Aircraft plant, which offered practically lifetime employment. In the major cities throughout the state, Kevin Starr (Golden Dreams: California in an Age of Abundance, 1950-1963) found confident new enterprises, fueling the state’s middle class with both stable blue-collar and white-collar jobs.

Today, the employee-employer relationship has become more distant, and job security has largely disappeared. In its place are variable, alternative types of employees: independent contractors, temporary workers, contract workers, leased workers, part-time workers, on-call workers, day laborers, and the self-employed.

Today, the employee-employer relationship has become more distant, and job security has largely disappeared. In its place are variable, alternative types of employees: independent contractors, temporary workers, contract workers, leased workers, part-time workers, on-call workers, day laborers, and the self-employed.

In 1995, the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) began to count workers in “alternative employment arrangements.” As the California labor economist Paul Wessen has noted, in the latest 2005 BLS “Contingent and Alternative Employment Arrangements” survey, roughly 1.5 million California workers are independent contractors who are outside of the payroll employment system. Another 481,000 workers are on-call workers (workers called to work only as needed); some 210,000 are temporary help agency workers; and 64,000 are workers provided by contract companies. Combined, they amount to 13 percent of California workers.

Not counted in these alternative work arrangements are other California workers without full-time, steady paychecks: part-time workers and self-employed business operators. In separate studies, the Economic Policy Institute and the AFL-CIO research division have estimated the percentage of workers in all of these “non-standard work arrangements” at 30 percent of the labor force. And that number leaves out the insecure employment in many standard payroll jobs in California. Certain occupations—particularly construction and agriculture—have long been characterized by seasonal and irregular work.

Today, no occupation is protected from layoffs or work interruptions. As late as 1979, when I entered the job world full-time in California, workers in the white-collar professions—in finance, real estate, law, insurance, health care management, education—could feel relatively safe after a number of years with a firm. Today no mortgage banker, investment banker, insurance executive, engineer, senior attorney, or healthcare manager is safe if she or he is not bringing in revenue. “Coffee is for closers,” Alec Baldwin’s character says in Glengarry Glen Ross, a bottom-line mindset that defines all occupations in California.

Today, no occupation is protected from layoffs or work interruptions. As late as 1979, when I entered the job world full-time in California, workers in the white-collar professions—in finance, real estate, law, insurance, health care management, education—could feel relatively safe after a number of years with a firm. Today no mortgage banker, investment banker, insurance executive, engineer, senior attorney, or healthcare manager is safe if she or he is not bringing in revenue. “Coffee is for closers,” Alec Baldwin’s character says in Glengarry Glen Ross, a bottom-line mindset that defines all occupations in California.

What is behind this change? Many of the same forces that have shaped employment nationwide: technology, the decline of private sector unions, the shifting culture of work, and most of all the rise of the global economy.

Technology has always been a force for job turnover in the state. Even in the roaring 1960s, state officials worried publicly that the automation of that period would leave many workers permanently unemployed. What is different today is the pace of technology.

Over the past decade, the speed of Internet commerce and social media business development has restructured California’s job world, particularly in retail, business services, and telecommunications. In my San Francisco neighborhood, businesses have always come and gone, but not with the speed of recent years. Borders bookstore, Blockbuster and Hollywood video stores, Mervyn’s department store—all crowded a few years ago—now are shuttered, casualties of Internet commerce.

Added to this march of technology is the decline of private sector unions in California (less than 8 percent of private-sector workers are unionized in the state) and the cultural shifts in employment. Employers will release employees as economics dictate, and employees will move to other employers with better economic offers—all, again, at a speed unthinkable a few decades ago.

The impact of technology and work culture pales in comparison to the changes wrought by the global economy. Few in California in the 1950s and 1960s recognized it at the time, but it’s clear that what we took to be the future was instead a brief interlude in economic history, when the United States and particularly California had economic dominance over a world economy wrecked by World War II.

By the 1970s, the rest of the world had begun to catch up. Beginning in the 1980s, our California heavy-manufacturing firms found themselves in global competition, and in the next decades this competition extended to finance, business services, accounting, technology, and even education. The confident large business enterprises of the ’50s and ’60s would soon find themselves retooling, cutting costs and personnel, outsourcing operations, or closing. The conventional wisdom is that all this insecurity and instability will only accelerate. In a new book called The Start Up of You, Reid Hoffman, founder of LinkedIn, argues that we all need to think of ourselves as start-ups: constantly selling ourselves, refreshing our skills, adapting to fast-changing business conditions. Hoffman and the conventional wisdom are probably right. For some Californians, those who possess the entrepreneurial skills and adaptive mental abilities, the new job world will be a blessing. For the rest—at least one-third of our labor force—it will be an even more difficult and challenging place.