This Friday, the Employment Development Department will be releasing the employment numbers for September and October. Most likely, they will follow the pattern we’ve seen for the past nearly three years of steady job gains and slowly reducing unemployment.

Since February 2010, the state has gained over 826,000 payroll jobs, an average of roughly 27,000 payroll jobs per month (29,100 payroll jobs gained in the latest month of August 2013). The official unemployment rate has declined steadily from over 12.5% in 2010 to 8.7% in July and slightly up to 8.9% in August. The post Great Recession in California at least on the surface has been a period of gradual employment improvements.

Yet, during this same time, a number of economists and futurists have come forward with a vision of a more stark and dystopian job future for California and elsewhere. This is a future in which technology means fewer and fewer workers needed for tasks, permanent job scarcity, and a sharply declining middle class. Tyler Cowen’s Average is Over, published in September, presents such a future, as does Jaron Lanier’s Who Owns the Future?, published in May, and James Huntington’s Work’s New Age, published in 2012.

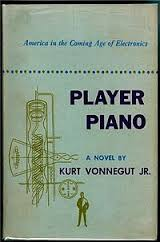

The dystopian job world in which technology replaces workers is not a new vision. In various forms it is portrayed in prominent twentieth century novels, including Aldous Huxley’s Brave New World (1932) and Kurt Vonnegut’s Piano Player (1952). In Piano Player, industrial automation has resulted in a ruling class of engineers and managers who create and maintain the machinery, and a larger class of others, who have no function in the economy.

The dystopian job world in which technology replaces workers is not a new vision. In various forms it is portrayed in prominent twentieth century novels, including Aldous Huxley’s Brave New World (1932) and Kurt Vonnegut’s Piano Player (1952). In Piano Player, industrial automation has resulted in a ruling class of engineers and managers who create and maintain the machinery, and a larger class of others, who have no function in the economy.

Jaron Lanier is a Californian (Berkeley), and well-known writer and futurist. In Lanier’s job future, the Internet technology rather than industrial automation is the driving economic force, in destroying jobs. Lanier is fond of comparing employment at Kodak and Instagram.

At one time Kodak was valued at $28 billion and employed 140,000 workers. When Instagram was sold to Facebook in 2012 for $1 billion, it employed 13 people. Lanier sees the Internet as eliminating paid structured employment, in favor of an informal, and largely unpaid, economy, ruled by a small number of technology managers and engineers.

At one time Kodak was valued at $28 billion and employed 140,000 workers. When Instagram was sold to Facebook in 2012 for $1 billion, it employed 13 people. Lanier sees the Internet as eliminating paid structured employment, in favor of an informal, and largely unpaid, economy, ruled by a small number of technology managers and engineers.

Are we heading to such a job future? Friday’s job numbers are likely to suggest a brighter employment prognosis for California. But this new literature on job dystopia should give us all pause about possible deeper economic currents in our state.