I’ll admit it, I was more than a little dismayed to read last week’s Los Angeles Times article explaining away Toyota’s decision to move its Torrance headquarters to Texas. The Times turned what seemed to be a teachable moment on the excesses of California regulation into little more than a business school case study:

“The trouble is that taxes, regulations and business climate appear to have had nothing to do with Toyota’s move. It came down to a simple matter of geography and a plan for corporate consolidation….”

To some extent, the Times can be forgiven for its view. That’s because it’s awfully hard to show statistically that government regulations cause companies to move or make other types of divestments. (Even a large scale policy change like Obamacare generated only anecdotes about this firm reducing workers to below 50, or that firm eliminating its company-run health plan.)

Why is it so difficult to connect the dots between California’s regulatory environment and business flight? There are a couple of reasons.

First, California’s current regulatory environment wasn’t created all at once, but was built up over decades through a process of accretion. Sure, there is the occasional big ticket legislation such as AB 32 and Green Chemistry that might shock the business community to visibly respond, but most regulatory changes are small and incremental. Examples under consideration this year include requirements that business provide all employees (including part-time workers) at least three days of paid sick leave (AB 1522, Gonzalez); more labeling of sugar-sweetened beverages for diabetes, obesity, and tooth decay (SB 1000, Monning); and, higher property taxes for businesses (SB 1021, Wolk).

Each individual piece of legislation might not be enough to cause a business to flee the state, but over time these individual pieces add up. So California businesses find themselves much like the frog in the pot of boiling water – as the regulatory temperature incrementally rises in the state, companies continue to endure… until they can no longer.

And second, companies today have many options to modify their operations, not all of which make the news. Consider a hypothetical company that has operations in both California and Texas. It is fairly easy see if the company shuts down its California operations and moves entirely to Texas. But it is less easy to see if the company simply decides to invest more in the Texas operations at the expense of the California operations. (On a side note, the Public Policy Institute of California found that between 1992 and 2004, multistate companies headquartered in California did grow their out-of-state operations at a faster rate than their in-state operations, although they considered the overall impact to California to be small.)

Thus, it’s not surprising that the Times would conclude that Toyota is relocating its Torrance facility simply because it makes business sense to be closer to its manufacturing operations. It’s just hard to show causation.

(On another side note, what is surprising is the Times’ failure to acknowledge that Toyota’s relocation might not have been necessary if the company were still producing cars in California. Don’t forget that between 1984 and 2010, Toyota jointly owned the NUMMI automotive plant in Fremont with General Motors. GM’s bankruptcy in 2009 presented Toyota with a choice of whether to continue the plant or close it, and they closed it. As Toyota considered its options, including consolidating its production in underutilized plants in the South, the Times actually admitted that “[f]ew auto industry experts would be surprised if Toyota pulled the plug. California is a high-cost manufacturing state.”)

That said, perhaps focusing attention on the actions of one company, Toyota, is misplaced because it obscures the bigger picture of what is happening in California. So let’s take a step back and try to generate a little agreement between those who criticize California’s regulatory climate and those who defend it.

Conventional wisdom tells us that California has a number of advantages going for it – great weather, an abundance of natural resources, top-notch research universities, hubs of technological innovation and artistic creativity, extensive trade-related infrastructure – and that these factors combine to make the state truly exceptional.

So what do the data say? (To quote the Times editorial from last week, “The numbers don’t lie….”)

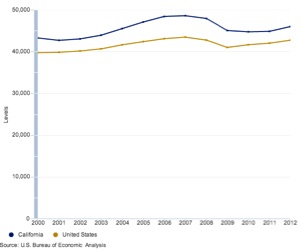

Looking at real per capita GDP, which is a simple and widely accepted measure of the wealth of a region that allows for fair comparisons, the data say that we’re above average. Figure 1 below from the U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis shows that in 2012, California had a real per capita GDP (in 2005 dollars) of just over $46,000. The United States as a whole had a real per capita GDP that same year of less than $43,000. And California’s real per capita GDP exceeded that of the United States in every year since 2000.

Figure 1. Real Per Capita GDP for California and the United States

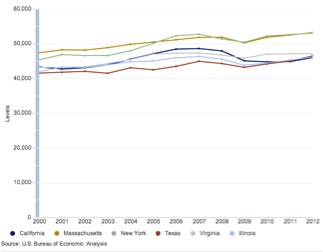

However, now compare California’s real per capita GDP to major states’ real per capita GDP. Figure 2 shows that today we’re essentially doing no better than Illinois, Virginia, and (you guessed it) Texas. We are actually surpassed by both New York and Massachusetts – and have been since 2000 – each with a real per capita GDP exceeding $53,000.

Figure 2. Real Per Capita GDP for California and Major States

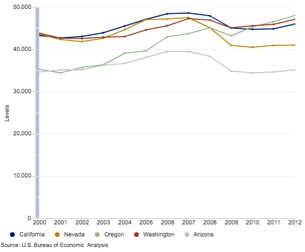

And compare California’s real per capita GDP to that of our regional neighbors. Figure 3 shows that while we’re doing better than Arizona and Nevada, we’re effectively being outperformed, if only slightly, by Oregon and Washington. Just sit with that thought a moment.

And compare California’s real per capita GDP to that of our regional neighbors. Figure 3 shows that while we’re doing better than Arizona and Nevada, we’re effectively being outperformed, if only slightly, by Oregon and Washington. Just sit with that thought a moment.

Figure 3. Real Per Capita GDP for California and Regional States

The bottom line: California doesn’t perform any better than most of the states we would expect it to. So if California considers itself to be above average, then everybody must be above average.

The bottom line: California doesn’t perform any better than most of the states we would expect it to. So if California considers itself to be above average, then everybody must be above average.

These findings remind me of Garrison Keillor’s Prairie Home Companion, with its news reports from the fictional Lake Wobegon. As everyone knows, in Lake Wobegon “all the women are strong, all the men are good-looking, and all the children are above average.”

Consequently, California faces a choice. Citizens and policymakers can help to make this state exceptional by rolling up their sleeves and performing the hard work needed to improve the state’s business climate, or we can continue to live under the fiction that everything is fine. Because make no mistake, today California is Lake Wobegon.

Dr. Justin L. Adams is the President and Chief Economist of Encina Advisors, LLC, a Davis-based research and analysis firm.