The decision last week by Tesla Motors to locate its battery factory in Nevada attracted the most media attention among economics stories, and generated a new wave of articles about California’s economic competitiveness. But our real concern should be not Tesla (California government did everything possible) but the decline in entrepreneurship in California as elsewhere, and missed opportunities for future Teslas.

Data on the decline of entrepreneurship in California comes from several sources over the past six months. The most prominent have been the Brookings Institution studies by economists Robert Litan and Ian Hathaway: “Declining Business Dynamism in the United States”, and “The Other Aging of America: The Increasing Dominance of Older Firms”. Another major study on declining business start-ups, “The Role of Entrepreneurship in US Job Creation and Economic Dynamism”, published in the Journal of Economic Perspectives, reinforces the narrative.

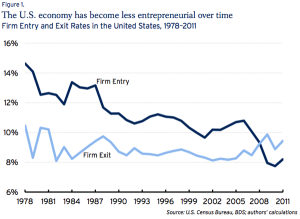

Here’s a chart, reprinted from the Litan and Hathaway “Declining Business Dynamism” study, that most clearly sets out the national dynamic. Declining entrepreneurship is not a new phenomenon, but it has picked up speed since 2006.

Each of the entrepreneurship studies utilizes nationwide data, and each is careful to emphasize that the entrepreneurship decline extends to all regions and states. So the decline is not limited to California, but neither is California exempt; and the state-by-state data that Litan and Hathaway include (Appendix B) show California around the middle of states in terms of declining rates.

Each of the entrepreneurship studies utilizes nationwide data, and each is careful to emphasize that the entrepreneurship decline extends to all regions and states. So the decline is not limited to California, but neither is California exempt; and the state-by-state data that Litan and Hathaway include (Appendix B) show California around the middle of states in terms of declining rates.

What explains the decline? What does it mean for California?

Litan and Hathaway examine several explanations: the shift of economic activity into retail and services and consolidation of firms in these sectors, increased regulations at all levels of government, higher taxes at all government levels. But they are hesitant to draw any conclusions. Robert J. Samuelson, who always writes perceptively about employment, suggests that the decline may be linked to the aging of the population (though the data show a rise in start-ups by older workers, which is consistent with the heightened barriers that older workers face in the economy).

Often in social policy, the most straightforward explanation is the best. So, in this case, we are led to the increasingly unfavorable incentive structure for entrepreneurship, that has grown over the past thirty years, and especially since 2006. At the center since 2006 is the greater uncertainty surrounding the national economy after the Great Recession, and even more so, the uncertainty linked to tax increases and threats of tax increases. These concerns add to the already significant level of business and personal taxes, the tightening of business lending, and the failure nationally of proposed reforms related to employment lawsuits.

Defenders of the current status quo of taxes and costs try to claim that the federal top marginal tax rates have fallen since the Reagan tax cut of 1981, during the period of declining entrepreneurship. However, prior to the 1981 tax cut, few taxpayers actually paid the top rates, and other state and local costs have grown since 1981. Taxes and costs are not the only factor, but they are a significant one—and the constant threats are almost as damaging as the imposition.

Despite the political rhetoric supporting entrepreneurs, nearly everything seems stacked against starting and running a business today. Rather than seek reasons to justify the decline in entrepreneurship, our policy bodies in California should be spurred by these studies to examine alternate cost structures. The Los Angeles Times story this past weekend on the rise in street vendors/entrepreneurs testifies to the resilience of entrepreneurial spirit and drive we have this state—if not, simultaneously, a current of employment desperation.