Gov. Brown wants state workers to begin paying half the cost of their future retiree health care — a big change for workers making no payments for coverage that can pay 100 percent of the premium for a retiree and 90 percent for their dependents.

The governor also wants state workers to be given the option of a lower-cost health insurance plan with higher deductibles. The state would contribute to a tax-deferred savings account to help cover out-of-pocket costs not covered by the plan.

More funding and lower premium costs are key parts of a plan to eliminate a growing debt or “unfunded liability” for state worker retiree health care, now estimated to be $72 billion over the next 30 years.

As Brown proposed a new state budget last week, he pointed to a chart showing retiree health care debt at a crossroads. If no action is taken, the debt by 2047-48 grows to $300 billion. Under his plan, the debt by 2044-45 drops to zero.

“So these are our promises,” he said, “and if we don’t take any action you are looking at hundreds of billions of dollars that we owe. And that’s why I am going to negotiate during our upcoming collective bargaining talks for the best deal I can get for the workers and the taxpayers.”

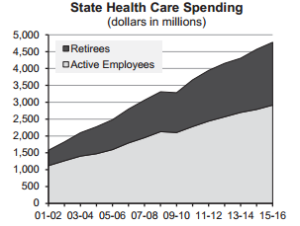

State worker retiree health care is one of the fastest-growing costs in the state budget. Next fiscal year its cost is $1.9 billion (1.6 percent of the general fund), four times more than paid 15 years ago, $458 million (0.6 percent of the general fund).

State worker retiree health care is one of the fastest-growing costs in the state budget. Next fiscal year its cost is $1.9 billion (1.6 percent of the general fund), four times more than paid 15 years ago, $458 million (0.6 percent of the general fund).

Brown’s plan would save taxpayers money by switching from “pay-as-you-go” funding, which only pays the health insurance premiums each year, to pension-like “prefunding” that invests additional money to earn interest.

Prefunding is widely urged as a way to cut long-term costs. The No. 1 recommendation of a governor’s public employee retirement commission in 2008 was prefunding retiree health care.

The California Public Employees Retirement System expects investments to pay two-thirds of total pension costs. The governor’s retiree health care plan is expected to save nearly $200 billion over the next 50 years.

When fully phased in, Brown’s plan is estimated to cost the state $600 million a year in addition to the payment of premiums. The amount is half of the “normal” cost of future retiree health care earned by active workers during a year, excluding debt from previous years.

State workers would contribute the other half of the normal cost, bringing the total to $1.2 billion. With $1.9 billion for premiums, the total is still well short of the $5 billion a state controller’s report last month said is needed for full funding.

Brown’s finance department said its cost estimates were developed with the same actuaries used by the controller, but a different scenario. Though not included in the estimates, California State University also is expected to prefund retiree health care.

In an annual “fiscal outlook” last November, nonpartisan Legislative Analyst Mac Taylor urged the Legislature to consider using the new Proposition 2 debt payment fund to pay state worker retiree health care debt.

Brown’s proposal to have workers help pay for retiree health care follows some large cities, such as San Jose and San Francisco, and his earlier experience with the Legislature.

The governor’s first retiree health care proposal, part of a 12-point pension reform, was dropped from the final version of the pension reform, AB 340 in 2012. An Assembly analysis said unions have “shown a willingness to bargain over the issue.”

The California Highway Patrol, giving up pay raises for several years, contributes 3.9 percent of pay to the state retiree health care investment fund with a state match of 2 percent of pay. Physicians, dentists and podiatrists (bargaining unit 12) and craft and maintenance (bargaining unit 16) contribute 0.5 percent of pay with no state match.

The governor’s proposal last week does not say how much of a bite from state worker paychecks will be needed to yield a total of $600 million, half of the retiree health care normal cost.

Brown’s first proposal in the 12-point pension reform did not include prefunding state worker retiree health care. But the new plan last week has all three of the retiree health care proposals that were in the first plan.

Ten years of service is needed to be eligible for retiree health care, beginning at 50 percent coverage and increasing to 100 percent after 20 years of service. For new hires, the plan pushes back the thresholds for new hires to 15 and 25 years.

The state pays more of the health care premium for retirees (100 percent retirees, 90 percent dependents) than for active workers (80 to 85 percent workers, 80 percent dependents). For new hires, the plan prevents a higher subsidy in retirement than received on the job.

CalPERS is asked to “increase efforts to ensure” seniors eligible for Medicare are switching to lower-cost supplemental plans. For family members, the plan calls for eligibility monitoring, some lower-cost coverage, and surcharges if covered at work.

President Obama’s health care act imposes a “Cadillac tax” on full-coverage “platinum” health plans in 2018, a move to control costs by encouraging employers to move toward plans with higher deductibles and more out-of-pocket expenses.

Brown’s plan directs CalPERS to offer workers the option of a high-deductible health plan. The state would contribute to the tax-deferred Health Savings Account of employees who choose the option to “defray higher out-of-pocket expenses.”

It’s not clear whether state payments for retiree health insurance, which are based on the average of the four highest-enrolled health plans, would be reduced if large numbers of active workers, whose premiums doubled in the last 10 years, opt for lower-cost plans.

In bargaining, a standard response to a proposed cut is to ask for an offsetting increase. When the largest state worker union agreed to an increase in employee pension contributions in 2010, the agreement included a pay raise in following years.

Brown’s plan presumably benefits state workers by making their retiree health care more secure. Costs are said to be growing at an “unsustainable pace.” Worker contributions might strengthen the legal argument that retiree health care is a “vested right” protected by contract law.

Meanwhile, the contrast with other workers grows. The number of large private firms (200 or more employees) offering any level of retiree health care dropped from 66 percent in 1988 to 28 percent in 2013, a Kaiser report said. Many California teachers have no employer retiree health care.

For state workers who retire early, retiree health care can be a major benefit. With at least five years of service, state workers are eligible to retire at age 50, age 52 if hired after Brown’s pension reform took effect on Jan. 1, 2013.

“The plan preserves retiree health benefits when the private sector is scaling back, maintains health plans, and continues the state’s substantial support for employee health care,” the governor’s budget summary said last week.

Reporter Ed Mendel covered the Capitol in Sacramento for nearly three decades, most recently for the San Diego Union-Tribune. More stories are at Calpensions.com.

Reporter Ed Mendel covered the Capitol in Sacramento for nearly three decades, most recently for the San Diego Union-Tribune. More stories are at Calpensions.com.

Cross-posted at Calpensions.com.