Something that rarely happens in California could result from Gov. Brown’s proposal to contain growing state worker retiree health care costs — benefits received by current government retirees might be reduced.

Part of the governor’s proposal allows state workers to choose a new low-cost health plan, increasing take-home pay. If enough choose the new option, the average cost of four health plans used to set retiree health care insurance payments would be lowered.

How many would choose the option is unknown. But the low-cost plan may have the potential to soon slow some of the rapid growth in health care costs, unlike other parts of the proposal that have delayed impact and require bargaining with labor unions.

Last week at a Senate and Assembly public retirement committee orientation, the new Senate chairman, Richard Pan, D-Sacramento, told a Brown administration official his committee will hold a hearing on the low-cost health plan proposal.

He did not mention “vested rights,” which under California court decisions protects public pensions from cuts. It’s been the central issue in attempts by local governments to cut retiree health care benefits in recent years.

Pan, a pediatrician and former chairman of the Assembly health committee, said “there are some policy concerns” about whether the low-cost options ensures state workers have access to adequate health care when they retire.

“I realize it’s voluntary but, having been a former health committee chair, voluntary still has certain implications on choices people make, and so forth, and how that can impact other employees,” Pan said.

The senator said his committee hearing on the low-cost health plan would be separate from budget committee action on the plan. Some past decisions on key budget issues have emerged from leadership meetings.

Odd as it may seem, the health care subsidy state workers receive when retired, often 100 percent of the insurance premium, is more generous than the subsidy on the job, usually 80 to 85 percent of the premium, depending on labor bargaining.

Active state workers once had the same full health care subsidy as retirees. Then in a state budget crunch in the early 1990s, the state saved money when workers agreed in labor contract bargaining to pick up some of the health care cost.

There is no labor bargaining for retirees. So retirees continue to receive the average payment of the four health plans with the largest state worker enrollment, which can cover 100 percent of the premium for retirees and 90 percent for their dependents.

The new state budget the governor proposed in January would give active state workers the option of choosing a low-cost health plan with a high “deductible” that must be paid out of pocket before insurance covers expenses.

To help workers who choose the low-cost plan pay deductible costs, the state would contribute to a tax-deferred “Health Savings Account,” a 401(k)-style individual investment plan.

President Obama’s health care act imposes a “Cadillac tax” on full-coverage “platinum” health plans in 2018, a move to control costs by encouraging employers to move toward plans with higher deductibles and more out-of-pocket expenses.

“The current ‘platinum’ level of health coverage leaves the state — and employees — vulnerable to to the pending Cadillac Tax,” the governor’s proposed state budget said in January.

After a pension reform in 2012 and a phased-in $5 billion annual rate increase last year for the underfunded California State Teachers Retirement System, Brown’s new budget plan would pay down a huge debt for retiree health care promised state workers.

After a pension reform in 2012 and a phased-in $5 billion annual rate increase last year for the underfunded California State Teachers Retirement System, Brown’s new budget plan would pay down a huge debt for retiree health care promised state workers.

The state worker retiree health care debt or “unfunded liability” is estimated to be $72 billion over the next 30 years. That’s more than the unfunded liability CalPERS reported for state worker pensions last year, $50 billion.

If nothing is done to contain the rapidly growing cost, the state worker retiree health care debt is expected to reach $90 billion in the next five years.

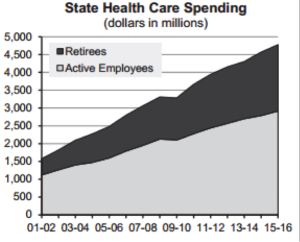

The state will spend an estimated $1.9 billion on retiree health care next year, four times as much as $458 million spent in 2001. Retiree health care will be 1.6 percent of the general fund, up from 0.6 percent 15 years ago.

Brown’s plan would save the state money in the future by switching from “pay-as-you-go” funding, which only pays the health insurance premiums each year, to pension-like “prefunding” that invests additional money to earn interest.

The budget calls for bargaining a 50-50 split between employers and employees of the retiree health care “normal” cost, the actuarially determined value of retiree health care earned by workers during a year.

For current state workers, prefunding would be a bite from their paycheck. The state estimates that its half of the retiree health care normal cost will be $600 million a year when prefunding is fully phased in.

“The proposal to eliminate the unfunded liability, by the state and our employees sharing in the cost of prefunding those benefits, is generally a matter of bargaining, and those will be pursued at the bargaining table,” Richard Gillihan, Brown’s Human Resources director, told the two committees last week.

Some state workers have begun prefunding retiree health care. The Highway Patrol contributes 3.9 percent of pay with a state match of 2 percent of pay. Two other small bargaining units contribute 0.5 percent of pay with no state match.

For the state, prefunding would be spending to save. Costs go up for years before investment earnings begin reducing annual expenses. The California Public Employees Retirement System, for example, expects investments to cover two-thirds of its pensions.

For new hires, in addition to sharing the normal cost the budget calls for bargaining longer service to become eligible for retiree health care and limiting state premium payments to the amount received while on the job.

Ten years of service is needed for state workers to be eligible for retiree health care, beginning at 50 percent coverage and increasing to 100 percent after 20 years. The proposed budget pushes back the thresholds to 15 and 25 years.

For current retirees, the low-cost health plan could indirectly be their contribution to containing state costs, if the number of state workers choosing the option is large enough to lower the four-plan average that sets their premium payment.

The low-cost health plan apparently would not be bargained. Legislation would direct CalPERS to begin offering the option among the health plans from which state workers can choose.

The low-cost health plan is similar to Brown’s proposal for a “hybrid” pension, combining a smaller pension with a 401(k)-style plan. It was rejected by the Legislature in 2012 when most of the governor’s 12-point pension reform was approved.

Reporter Ed Mendel covered the Capitol in Sacramento for nearly three decades, most recently for the San Diego Union-Tribune.