(Editor’s Note: This short essay originally appeared, in slightly different form in the Sunday San Francisco Chronicle Insight section, March 22, 2015).

Though the idea of a second BART tube has been discussed over the past twenty-five years, in just the past few months it has assumed a striking new momentum.

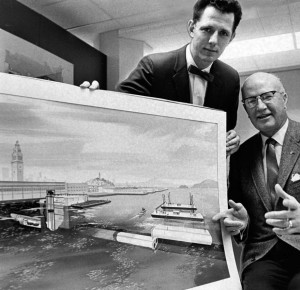

The photo to the left is of engineers with the Peter Kiewit Company, which built the BART bay tube, showing an artist’s sketch of the tube in 1966 (click to enlarge). The 3.6 mile tube was completed in 1969, and opened for service in 1974. It is the sole link of the East Bay BART trains into San Francisco and to San Mateo and the San Francisco Airport.

A front-page article in the San Francisco Chronicle on a second tube early this year has been followed by several opinion pieces in favor, blog postings, and declarations of support from Mayors Ed Lee and Libby Schaaf. San Francisco Supervisor Scott Wiener is actively pushing the idea, as is Mayor Lee and his staff. In April, the BART Board will be asked to support a major study of planning and evaluation.

So as the momentum develops, it is time to briefly note the changing travel dynamics driving this momentum, where the funding might come from, and whether the project may finally have reached a tipping point.

Travel patterns in the Bay Area have been evolving since the opening of the BART system, and continue to evolve. One of the central principles on which the BART system was built, that of commuters coming from housing in the suburbs to the central cities of San Francisco and Oakland, was already out of date when BART opened in 1972. And the dispersion of jobs throughout the region and multiplicity of commute routes has only grown since.

What has changed in the past few years, though, are dynamics of system capacity and back-up. First, are the heightened concerns about the fragility of a single tube: the current tube is in need of repairs, and has no backup if there is a breach, through intentional act or accident. Second, the intense residential and commercial development pattern of South of Market has generated demand for direct transit service to that area, as well the growing interest in infill stations in the East Bay and San Francisco. Third, and perhaps most important, is the lack of capacity on the current system. As any BART rider can testify, the system is overloaded, standing room only during rush hours, more frequent delays and breakdowns.

Several options for a second tube have been presented that would bring major transit gains. One option, for example, is of a line from the current MacArthur station that would go south with stations at Lakeshore/Grand and 9th/Laney in Oakland, a station in the City of Alameda, and then a second BART crossing to Mission Bay, with several stations in Potrero Hill and the Bayview. A second option is to cross from Alameda to Mission Bay, continuing to Civic Center and then out to the west side of San Francisco.

From the start, two central issues of cost and timing must be honestly addressed. Major infrastructure projects almost always achieve high positive polling numbers when they are described in the abstract, until the cost issue is introduced. The early very rough estimates for a second tube are in the range of $10-$12 billion. Funding suggestions have revolved around Cap and Trade funds, federal and state transportation funds, parking fees, and vehicle license fees, but even if possible these would not be sufficient. From the start, it should be clear that some new source of dedicated revenue will be needed requiring a Bay Area vote. That’s the way it should be.

Second, if business-as-usual is followed, a second tube can take two decades or more (some estimates are for 30 years). Any project approach must include a sense of urgency and willingness to expedite processes, before any implementation funding is committed. If on a small scale, the rebuild of the Santa Monica freeway in Southern California in 1994 and the rebuild of the MacArthur Maze in 2007, both completed months before the most optimistic projections, show the possibilities when a sense of urgency is present, and expedited processes are employed. The rebuilding of the Bay Bridge, years behind schedule, shows the opposite.

Large-scale California transit projects near always have required a long period of gestation, in which concepts are presented, discussed, dismissed as impractical or too expensive, set aside. But they may not be forgotten and a combination of forces comes together to achieve a type of tipping point in implementation. Traffic gridlock significantly worsens, or technological advances increase feasibility or reduce costs, or new funding becomes available, or usually a combination of these elements, combined with one or several project champions. This is the arc largely followed by the fourth bore of the Caldecott, the Highway 4 widening, the BART extension to San Jose, and even for the basic BART system itself—which was first seriously discussed in the late 1940s.

It may be that the second tube is reaching its tipping point. The BART Board’s decision in the next month will be one indication.

Michael Bernick is a former BART director (1988-1996). His most recent book, with Richard Holden, is The Autism Job Club: The Neurodiverse Workforce in the New Normal of Employment (2015).