Gov. Brown’s plan to curb the long-ignored debt for state worker retiree health care, now much larger than their unfunded pension debt, may look familiar. It’s similar to the standard state and local government pension reform.

Workers contribute more, most going from zero to 3 percent of pay, and new hires not protected by vested rights get lower benefits, working five years longer to get health coverage capped at what they received on the job.

Last week, the nonpartisan Legislative Analyst’s Office, noting that most of the plan bypasses the Legislature, recommended that lawmakers hold hearings on state worker retiree health care, going back to square one, 1961, when the benefit began.

Times were different then. Workers were at risk of losing health coverage when they retired. The cost might be unaffordable, or the worker might have a health condition causing insurers to deny coverage.

Now state workers are eligible for federal Medicare at age 65. They are expected to stay on the job longer under Brown’s pension reform in 2013, which requires new hires to work four more years to get the same pension formula as previous hires.

And prior to Medicare eligibility, President Obama’s Affordable Care Act can provide low-cost health insurance coverage, pre-existing conditions included, and sometimes with subsidies.

As an alternative to the long-term debt of retiree health care, the state could offer new hires increased pay or contributions to a supplemental fund that could be used for health coverage or other purposes.

“Before California builds a funding model to pay for this benefit (retiree health care) for decades to come, the Legislature should consider whether this benefit should continue to be a part of the state employee compensation package for new hires,” said the analyst’s report prepared by Nick Schroeder and reviewed by Marianne O’Malley.

“If prospective employees do not value this benefit as much as it costs, the state and the new employee might be better off if the state offered future employees an alternative form of compensation.”

The Analyst’s report said there is “some ambiguity” about whether retiree health care, like pensions, is a vested right under state court decisions based on contract law, preventing cuts in the benefit offered at hire unless offset by a comparable new benefit.

If the state requires worker contributions under Brown’s plan, the contractual right to retiree health care could be strengthened, reducing future options for change. Some state workers have begun retiree health care contributions.

The Highway Patrol contributes 3.9 percent of pay with a state match of 2 percent of pay. Two other small bargaining units, doctors and maintenance workers, contribute 0.5 percent of pay with no state match.

Another way retiree health care differs from pensions is “prefunding.” Money is invested to help cover the future costs of retirement benefits earned by workers during the year.

“A fundamental principle of public finance is that costs should be paid the year in which they are incurred,” said the Analyst’s report.

Investment earnings are expected to pay two-thirds of the future costs of California Public Employees Retirement System pensions. Legislation in the early 1990s created a state worker retiree health care investment fund.

But lawmakers never put money in the fund, choosing instead to pass the buck to future generations, forcing them to pay for services they did not receive.

Now the debt or “unfunded liability” for retiree health care promised current state workers over the next 30 years is $72 billion, an actuarial report issued by the state controller last December estimated.

That’s more than the unfunded liability for state worker pensions reported by CalPERS last year, $50 billion. And nearly as much as the $74 billion unfunded liability reported by the California State Teachers Retirement System last year.

After a modest cost-cutting pension reform in 2012 and a major funding increase for CalSTRS last year, Brown is addressing what the Analyst called “the state’s last major liability that needs a funding plan.”

Before Brown issued his plan in January, the Analyst had suggested that the Legislature consider using a new debt-payment fund created by voter approval of Proposition 2 last fall to reduce the state worker retiree health care debt.

The Analyst’s report last week criticized the governor’s plan to bargain a 50-50 split between the state and workers of the “normal” cost, the actuarially determined value of retiree health care earned during a year, excluding debt from previous years.

Workers contributing an estimated 3 percent of pay might receive nothing in return if they leave state service before vesting in retiree health care. Vesting currently begins after 10 years and would be delayed to 15 years under the governor’s plan.

The 50-50 split of the pension normal cost under the governor’s reform was offset by pay increases, the Analyst said, and a “large segment” of the state workforce is not paying its normal cost share: California State University, the courts, and the Legislature.

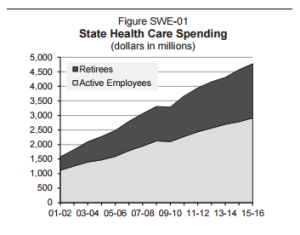

Another problem is that under the governor’s plan to pay down the unfunded liability, current state retiree health care costs (see chart below) would sharply escalate, tripling in today’s dollars in 30 years.

“This amortization schedule reduces cost pressures in the short term, but would require the Legislature to make significant budgetary cuts or revenue increases in the future,” the Analyst said.

Part of the governor’s proposal calls on CalPERS, the health plan administrator, to give state workers the option of choosing a low-cost plan with a high “deductible” that must be paid out of pocket before insurance coverage begins.

CalPERS has an annual deductible of $500 per member, limited to $1,000 per family, excluding preventive services if they are done by a preferred provider. A $20 office visit fee at preferred providers counts toward the deductible.

In contrast, the President’s Affordable Care Act allows annual deductibles as high as $6,600 per person and $13,200 per family. Brown’s proposal, not specifying a deductible amount, would contribute to a savings account to help pay out-of-pocket costs.

At a legislative informational hearing on high-deductible plans last week, opponents said high out-of-pocket expenses discourage visits to health providers, reducing preventive care that keeps members healthy and cuts long-term costs.

“Any serious review of the literature around the high-deductible health plan shows that they undermine patient health and long-term cost control,” Terry Brennand, SEIU California, told the hearing.

The low cost of a high-deductible plan can give members more take-home pay. In the most popular state worker plan, Kaiser, the state worker pays $278 a month, which is about 17 percent of the total premium, the Analyst’s report said.

If enough workers choose the new option, the high-deductible plan could become one of the four health plans with the highest enrollment that are used to set retiree health care payments, lowering them.

“The high-deductible plan is a back-door way to reduce the health care reimbursement promised to us retirees,” said Tim Behrens, California State Retirees president.

Reporter Ed Mendel covered the Capitol in Sacramento for nearly three decades, most recently for the San Diego Union-Tribune. More stories are at Calpensions.com.

Reporter Ed Mendel covered the Capitol in Sacramento for nearly three decades, most recently for the San Diego Union-Tribune. More stories are at Calpensions.com.