Despite being saddled with criticism ranging from narcissism to laziness, many millennials have stuck with the plan. You know the plan: Work hard in school, go to college and maybe grad school and you will end up with a well-paying job and a home of your own.

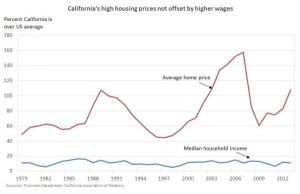

Somewhere along the line this plan became more of a fantasy, especially in California. Over the last 30 years, the precipitous rise in the state’s housing prices has far exceeded the change in median income. Compared to other states, California home prices appear untethered to the incomes actually earned by residents. The lack of affordable housing has caused California to lose some of its best young talent.

Somewhere along the line this plan became more of a fantasy, especially in California. Over the last 30 years, the precipitous rise in the state’s housing prices has far exceeded the change in median income. Compared to other states, California home prices appear untethered to the incomes actually earned by residents. The lack of affordable housing has caused California to lose some of its best young talent.

In the last 20 years, California has seen an exodus of almost 4 million people to other U.S. states. Most of those leaving were young families, the group most likely to become first-time homebuyers. The general lack of affordability has been driven not only by the state’s desirability and low inventory in many areas, but its tax policies. Proposition 13, in particular, primarily benefits current homeowners, inheritors, and real estate investors. The 1978 law, which originated as a ballot initiative, assessed property taxes based on a home’s 1975 value while allowing a 2 percent annual increase. A change in ownership or the completion of new construction are the only criteria for reassessment.

Millennials were raised in an era of flat incomes and rising costs for education and health care. Many struggle under their student loan obligations. Those burdens are exacerbated by a tax structure focused on yesterday’s conditions rather than future needs. For example, pre-1978 tax policies supported quality, affordable K-12 and community college education. Since then, the quality of education has declined and prices have climbed. Likewise, younger people have drawn the short straw when it comes to housing. According to the National Association of Realtors’ Housing Affordability Index for 2015, just 30 percent of households with the California median income can afford to purchase — a tough environment for prospective buyers who haven’t had the chance to build up assets. The disparity between income and homeownership only widens in the major cities. In San Francisco, for instance, affordability has fallen below 20 percent.

Entrenched homeowners, on the other hand, are in no hurry to see their multidecade windfall end. They’ve benefited not only from hot property markets and low taxes, but density limits. Culturally speaking, Californians oppose denser development, especially in the big cities. Zoning standards are restrictive, by and large, and heated battles over density have been fought in San Francisco, Napa County, Los Angeles, and Hollywood.

Beyond cultural issues, Proposition 13 hardens the generational barrier by discouraging longtime homeowners from selling and relocating. Such policies also motivate cities to build commercial real estate rather than residential to recover lost revenue through increased sales tax. Property taxes, and residential development, don’t generate the same payback over time.

Without substantial new home building, demand will outstrip supply for the foreseeable future. In California’s metro areas, the younger workforce is virtually priced out of the property market, forced to dedicate greater portions of their incomes to rent and commute from longer distances. Acknowledging this obstacle, Los Angeles Mayor Eric Garcetti wants to add 100,000 units to the city’s housing stock by 2021. But even that goal falls far short of the need. Nor has the mayor addressed the restrictive local zoning and building permitting processes.

The Proposition 13 reform agenda has compiled a record as a political nonstarter. Perhaps for good reason. In 1978, the law answered longtime complaints of overtaxation. Thirty-seven years later, as the millennial electorate embarks on its path to political ascendency, a new generation of young policy leaders is likely to address the intensifying debate over social mobility. If millennials can’t buy homes and create households, California will pay a cost. Why must this generation support a state of affairs that undermines growth and the state’s long-term interests while stockpiling gains for those who bought homes when homes were affordable?

For California, the policy challenge lies in fitting together a more nuanced approach to housing density, social mobility, and tax policy. A solution that links property taxes to today’s values could accelerate increases in supply while possibly moderating rising prices. Crucially, it would also provide an opening to an excluded population, a generation that has been deprived of the benefits of homeownership and membership in the middle class.

Originally appeared on Currency of Ideas, the blog of the Milken Institute