In Fall 2015, we have reached a neurodiversity moment in California.

In Fall 2015, we have reached a neurodiversity moment in California.

Conferences on neurodiversity are being held on a regular basis, such as the “Neurodiversity in the High Tech Workforce” conference held recently at the Microsoft campus in Mountain View. Over 150 persons from throughout Silicon Valley gathered to hear neuroscientists and Silicon Valley venture capitalists praise the strengths that persons with autism, dyslexia, ADHD and other learning differences bring to the workplace and American economy.

A growing industry of “Neurodiversity advocates” is emerging, as well as books with titles on neurodiversity and even “neurotribes”. Running throughout all of these is the neurodiversity theme: neurological (brain wiring) differences, traditionally seen as disadvantages in the work world, are really advantages, especially in the emerging knowledge-based economy.

Yet while the empowerment rhetoric of neurodiversity is finding an audience, there remains a big gap between the rhetoric of valuing adults with brain-wiring differences and the realities of the job market in California. Autism is the fastest growing of the neurodiverse conditions in California, and unemployment rates for adults with autism continue to be estimated at over fifty percent. Even as the economy continues to improve, there is a good deal of competition among job seekers for each opening. Neurodiverse adults are not faring well in the competition, and even when hired are not faring well in retention.

EXPANDability, based in San Jose, is one of the leading job training agencies in California serving adults with “disabilities”. Like other local employment agencies serving this population, EXPANDability’s population has shifted considerably in the past decade from individuals with physical disabilities to a larger percentage of individuals with neurological conditions.

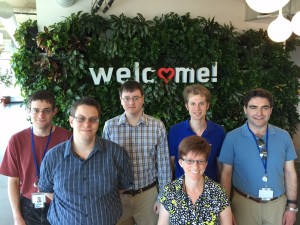

EXPANDability is part of the “Autism at Work” program at software giant SAP (the recent Autism at Work hires are shown above) and at Microsoft. Both of these programs have well-developed recruitment and retention structures to employ and retain adults with autism in tech positions. However, despite the extensive publicity both programs have received, the numbers of participants remain modest—the first SAP cycle in 2014 involved nine trainees in the bay Area, while the Microsoft program is starting with 10 participants.

Most of EXPANDability’s placements are outside of tech. In theory, EXPANDability seeks to tailor the job around the neurodiverse job seeker’s individual passions and skills. But passion and expertise are not easily translated into a specific job open at a particular time in a particular area.

Maria Nicholacoudis (below) is the Executive Director of EXPANDability, as well as the chair of the California Committee on the Employment of Workers with Disabilities. Nicholacoudis notes that beyond placement is the often greater challenge of retention. Many of EXPANDability’s neurodiverse clients do not easily fit into a company structure and workplace rules. Some have issues with hoarding paper or food, and do so in their work stations; others have personal hygiene issues, or can’t seem to get to the job site or come back from breaks on time. “Placement is the first step of employment, and often the easiest one,” Nicholacoudis notes; “That’s why we give a great deal of attention to retention after placement, to job coaching and supports, and to getting buy-in from throughout the company.” Worksite supports, though, are labor intensive and costly, especially the job coaches who can facilitate a transition period.

EXPANDability is constantly looking at new placement strategies for its neurodiverse clients. In recent years it has added a staffing company that allows employers to take on workers on a temporary basis, and evaluate their performances. “The staffing approach enables our workers to get in the door, which is the chief challenge in employment today, and show what they can do, and how their positive attitudes can improve the workplace,” explains Priscilla Azcueta, the staffing company director. One of her recent placements was an administrative assistant at the University of California, Santa Cruz. “The university had hesitations at first, but liked him so much it has led to a permanent position.”

There is no quick path going forward to translate neurodiversity rhetoric into an employment reality. The next years will be slow building on a mix of efforts among local agencies, our community colleges and universities, advocates and parents.

Fortunately, there is a richness of thought and activity, already underway among each of these entities in California. EXPANDability is only one of tens of job training agencies in California—ranging from the ARCs and Best Buddies throughout the state, to Resources for Independence Central Valley, Positive Resource Center, and the Cerebral Palsy Center in Oakland –testing measures of placement, retention and workplace culture. EDD meanwhile has its own Disability Employment Accelerator, an applied research effort to place individuals and test approaches.

Up at the California Community Colleges Chancellor’s Office, Rhonda Mohr, Scott Berenson and Scott Valverde of the Student Services and Special Programs division are engaged in several initiatives to expand neurodiverse participation on campus, both in degree granting programs and in career technical education and certifications (College to Career). On a district level, Contra Costa Community College District trustees Gordon, Enholm and Farley are examining more effective education models for the area’s growing neurodiverse student population. Nearby at UC Berkeley, Paul Hippolitus has joined with San Diego State Professor Caren Sax on a “Bridging the Gap” project for improved placement of neurodiverse students who are obtaining degrees. Outside of Sacramento, entrepreneur Marc Turtletaub is heading a team building Meristem, a new campus and living community serving adults with autism.

Most of all there are the parents and advocates, and the hundreds of individual efforts of inclusion springing up around the state: Dr. Lou Vismara and his projects of community building in Sacramento, Brian Miller and the Parent Advocates Seeking Solutions group in San Diego, Jill Escher and the Bay Area Autism Society’s quest for housing models, Alisa Wolf and Actors for Autism in Los Angeles, to mention just a few of the wide range of extra-governmental initiatives.

Of course, the efforts are not limited to California. This past week brings news of a new Neurodiversity Institute being launched by former boxer and orthopedic surgeon Harold “Hackie” Reitman. Hackie has teamed with Lynne Wines, a former bank chief executive, to develop this nationwide Institute, whose missions include collaborating with individual employers on “the tools needed to understand people with brains that work a little bit differently, while maximizing their unique abilities for the good of the company, the individual, and society.”

This summer brought a lot of good feeling about inclusion with the Special Olympics World Games in Los Angeles. Now the Special Olympics are over, and now for the hard part.

(A version of this essay appeared earlier in Zocalo Public Square.)