The latest financial statements of the state’s fifth largest school district, Elk Grove Unified, list a pension debt of $414.6 million, up from no pension debt in the statement for the previous year.

How did the debt go from zero to hundreds of millions in a year?

As you might guess, it didn’t. The change is how the pension debt is reported under a new rule of the Governmental Accounting Standards board that took effect last fiscal year.

School districts are required to begin reporting their share of a pension debt that previously had been reported only by the two big statewide retirement systems for teachers and non-teaching employees.

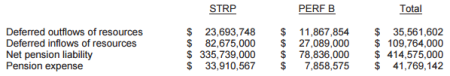

Elk Grove reported $335.7 million as its share of the “net pension liability” of the California State Teachers Retirement System and $78.8 million for the California Public Employees Retirement System.

Most employees in the 65 schools of the district in Elk Grove, a city of 160,000 near Sacramento incorporated in 2000 during rapid growth, are teachers eligible for CalSTRS. Non-teaching employees are in CalPERS.

The potential impact of the new accounting rule, GASB 68, may have played a role in the endgame for legislation that gave CalSTRS a long-delayed major rate increase signed by Gov. Brown in June 2014, only a week before the last fiscal year began.

Without a rate increase, actuaries said, the new accounting rule could require CalSTRS to report the nation’s largest pension debt, $167 billion, an amount so large some feared it might increase the cost of issuing school bonds.

Jack Ehnes, CalSTRS chief executive officer, told the board in September 2014 that while talking to school officials he found a mixed view about the impact of reporting a huge pension debt.

“Some arguing it would have no effect if people understood the basis for this,” he said, “others arguing that it would have a significant effect on the bond market for schools. So, the question was out there.”

After the rate increase was passed in the nick of time, the debt or net pension liability CalSTRS reported for the first year under the new accounting rule dropped to $58.4 billion.

But the new GASB reports (different from the way actuaries will continue to calculate funding requirements) are intended to not only put a spotlight on pension debt with a more prominent display, but also to more quickly show changes.

That’s already happened for CalSTRS. The first reports required under the new accounting rule were for fiscal 2014-15, when the CalSTRS net pension liability, $58.4 billion, was based on the fiscal year that ended June 30, 2014.

The next annual reports will be based on the CalSTRS net pension liability for the fiscal year that ended June 30 2015, which jumped to $67.3 billion mainly because pension fund earnings dropped from 18.7 percent in 2013-14 to 4.8 percent in 2014-15.

Elk Grove Unified financial statements show pension debt, p. 31

The new accounting rule was adopted during a time when estimates of state and local government pension debt nationwide ballooned to alarming levels, notably $2.2 trillion by Moody’s, a Wall Street credit rating firm.

Pension fund investments had huge losses during the financial crisis. The CalPERS portfolio plunged from $260 billion in 2007 to $160 billion in 2009 and now, nearly a decade later, is $280 billion as some see warnings of a new recession.

Moody’s and others contended that public pension funds have overly optimistic earnings forecasts (7.5 percent a year for CalPERS and CalSTRS) that conceal massive debt and the need for higher employer-employee contributions, benefit cuts or both.

The new GASB rule is a compromise between the status quo and lower earnings forecasts used by Moody’s, 5.5 percent, or an even lower risk-free bond rate that some economists think should be used for risk-free guaranteed payments like pensions.

Under the new rule adopted by GASB in 2012 after a lengthy process that began in 2006, pension systems are allowed to continue to use their own earnings forecasts to offset or discount the cost of pensions promised in the future.

But if their projected assets fall short, the rule requires pension systems to “crossover” to a lower bond-based earnings forecast to discount the remainder of their future pension costs.

“I’m seeing a lot of media basically saying there is going to be sticker shock when these things come out,” Alan Milligan, CalPERS chief actuary,said in 2011 of financial reports under the new GASB rule. “I’m not so sure about that.”

One reason for new CalPERS actuarial methods adopted in 2013 was better alignment with the new GASB rule. More importantly, like most California pension systems, CalPERS can raise employer rates and stay on the path to full funding.

The great exception, CalSTRS, lacks the power to raise most employer rates. But as noted, the Legislature, after years of urging, approved a large CalSTRS rate increase (AB 1469 in 2014) shortly before the new GASB rule took effect.

So, the Elk Grove Unified financial statement for last fiscal year said that its CalPERS and CalSTRS debt were both calculated without a crossover to the lower bond-based earnings forecast.

CalSTRS has a single plan and does not provide a net pension liability for school districts and other employers. Guidance on a website shows them how to calculate their share of the CalSTRS debt under the new rule.

CalPERS has more than 2,000 state and local government plans and has calculated a net pension liability for each, charging $2,500 per plan. The big system passed its first test to avoid a crossover to a lower bond rate and expects that to continue.

A look at two CalPERS plans shows little difference between the old “unfunded liability” debt, reported under the actuarial rules used to set annual employer contribution rates, and the new “net pension liability” debt reported under the GASB rule.

As of June 30, 2014, the San Bernardino police and firefighter unfunded liability was $162 million and the net pension liability $167.7 million; the Sacramento police and firefighter unfunded liability $375.2 million and the net pension liability $373.9 million.

A GASB rule adopted in 2004 told state and local governments to begin reporting the cost of retiree health care promised workers, a major long-term debt that often had not been calculated.

The new focus under the accounting rule was followed by a trend toward pension-like “prefunding” of retiree health care, making annual payments to an investment fund to help pay for benefits promised in the future.

A CalPERS retiree health care fund established in 2007 had investments from 471 local governments valued at $4.6 billion at the end of last year. The Brown administration is negotiating retiree health care prefunding with state worker unions.

Last year, GASB followed up by directing government employers to begin reporting their retiree health care debt in 2018 much like pension debt is reported under the new accounting rule.

Reporter Ed Mendel covered the Capitol in Sacramento for nearly three decades, most recently for the San Diego Union-Tribune.

Cross-posted at CalPensions.