Rows of newly minted model homes unspool across a verdant, rolling landscape in this sprawling master-planned community near Sacramento.

Solar panels glint across 1,000 acres of rooftops. On a tidy cul-de-sac, a faux-grass lawn flanks the driveway to the home of the future.

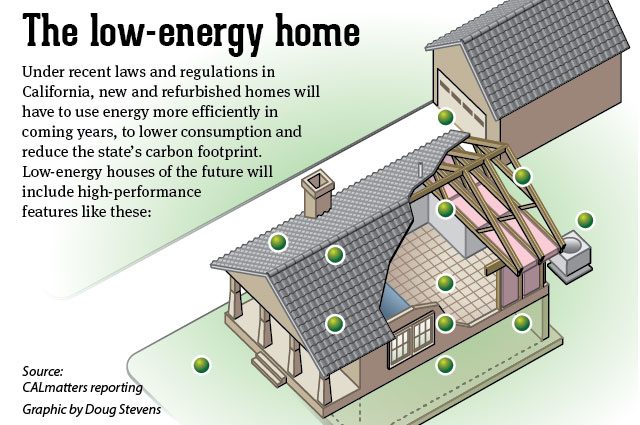

The two-story residence brims with state-of-the-art energy-saving technology: highly efficient heating and cooling systems, dense wall insulation, triple-paned windows, smog-gobbling roof tiles and “smart” appliances that spring into action when power demand is lowest.

Power-sipping homes like this will be critical to the state’s recalibrated energy policies. Those policies now include a law that requires California’s built environment—tens of millions of structures—to operate twice as efficiently by the year 2030, slashing consumption of electricity and natural gas to half their projected levels.

The mandate, intended to reduce the state’s need for carbon-spewing power plants, is part of California’s mission to address climate change by cutting greenhouse-gas emissions. Residential and commercial buildings account for about 20 percent of those pollutants.

The low-energy home

Exactly how the state’s ambitious goal will be achieved is unclear, and agreement on the price tag is elusive. What is certain is that making homes and other buildings use energy more efficiently will cost money up front, in a state that has some of the country’s most expensive real estate and is struggling to create more affordable housing.

California home prices are more than twice the national average, according to the nonpartisan Legislative Analyst’s Office.

Officials and some builders insist that consumers and businesses will save money in the long run as utility bills shrink and the resale value of houses and commercial structures increases.

Others view the goal as something more akin to the well-appointed homes in El Dorado Hills: a lovely thing to aspire to, difficult to reach.

There is, however, wide agreement on the enormity of the task, which builds on policies requiring more reliance on renewable-energy sources such as sun and wind and fostering mass transit to get cars off the road.

“This is a long-term project,” said Andrew McAllister, a member of the California Energy Commission. “Everyone has to play a part. There’s no one big solution, no silver bullet. There is a lot of silver buckshot.”

The new law, created last year by Gov. Jerry Brown and the legislature, offers no blueprint for implementing a policy that could touch millions of homes and nearly every school, church, office building and shopping center in California.

No action is required for existing homes or commercial buildings unless they undergo significant renovations. And the law stipulates that its implementation not be financially onerous for Californians.

But important questions of exactly how much the policy will ultimately cost and who will pay are unresolved, despite related legislation passed to help with the expense.

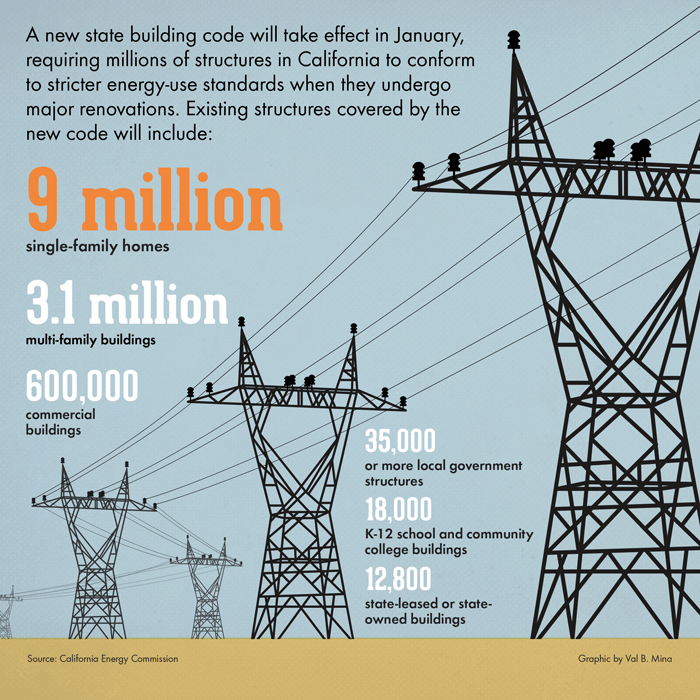

A new building code will cover many existing structures

There are other fundamental questions as well, such as exactly how to measure efficiency, where to start — Brown has suggested beginning with state-owned structures — and how energy upgrades will affect the state’s scarce low-income housing supply.

The task of figuring things out lies largely with the Energy Commission and the Public Utilities Commission. The agencies say they hope to know by the middle of next year how to update a tangle of existing building codes and other regulations, modernize the state’s electricity grid to incorporate more renewable energy and craft an educational campaign to inform consumers of what’s coming.

The Air Resources Board, which regulates air quality in California, will help, as will the major utilities.

“The details are not fleshed out. But to reach our climate targets, investing in energy efficiency is important,” said Sen. Fran Pavley (D-Agoura Hills), author of a landmark California law, signed in 2006 by then-Gov. Arnold Schwarzenegger, that launched a comprehensive effort to combat climate change.

“It’s going to be costly,” Pavley said. “…To me, the challenge is how to implement the upfront capital cost.”

When Brown signed the energy-efficiency bill into law last year, he described the changing climate as a “catastrophe” and called on Californians to do their part.

In fact, California has been on an energy diet for decades. Many of the state’s energy programs date to Brown’s first tenure as governor in the 1970s, a response to an oil embargo that sent gasoline prices into the stratosphere. His administration wrote energy efficiency into the building code, and California became the first state to create strict energy standards for appliances.

Per capita electricity consumption here has remained mostly flat since 1975, while national energy use has gone up 50 percent, according to the federal Energy Information Assn. Additionally, even though electricity rates in California exceed the national average, residents’ annual bills are among the lowest in the country. California’s aggressive appliance standards, for example, have saved consumers $75 billion since appliance efficiency programs launched in 1978, a state analysis says.

The state energy commission estimates that new building codes alone will save Californians $1.6 billion over the next 30 years.

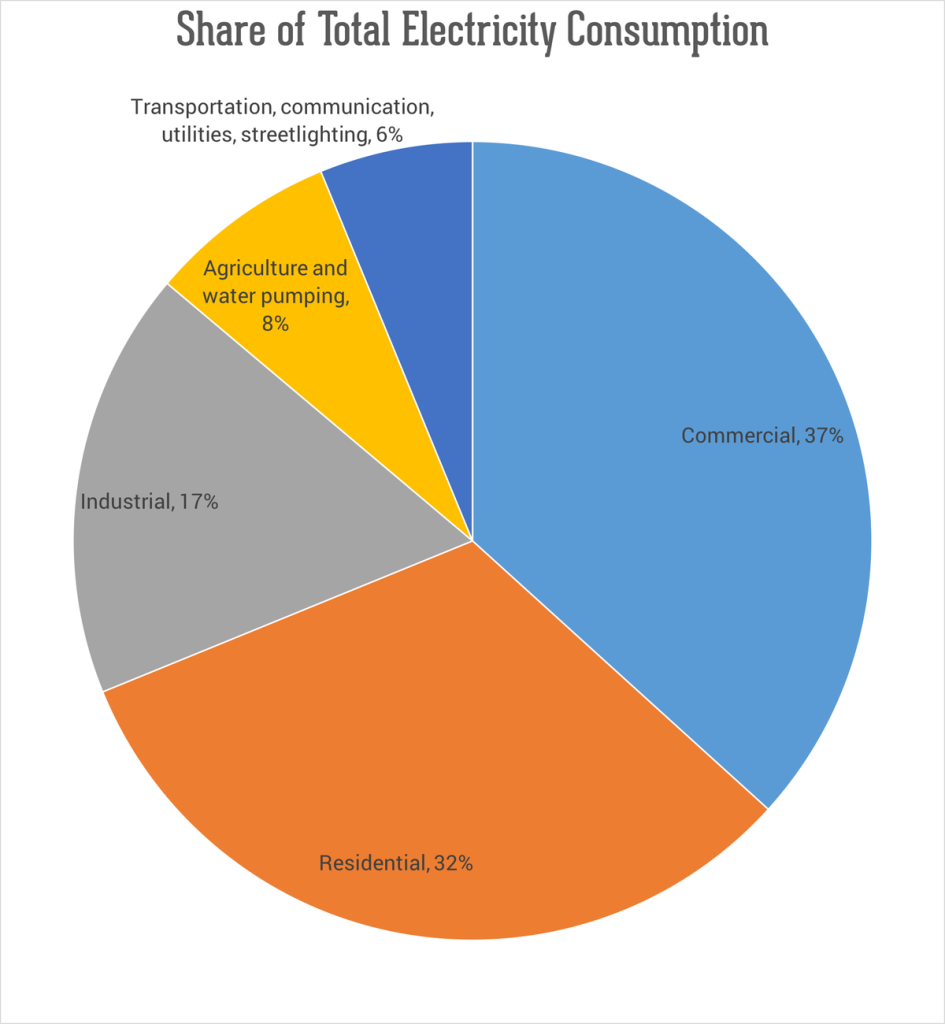

For example, although the building code is ratcheted up periodically to reflect technological advances, at least half of existing structures were erected before 1978, according to the state commission. Residential and commercial buildings account for about two-thirds of statewide electricity use, so there’s a lot of catching up to do in some quarters.

For the moment, and until the state’s approach is fleshed out, progress toward the government’s new targets rests heavily on the building code, which is revised every three years. It won’t fully reflect the new law until 2020, but the latest update, to take effect Jan. 1 of next year, does require a higher degree of efficiency.

Who uses California’s power?

Starting in January, homeowners who embark on major renovations—the type that trigger permits and inspections—may have new requirements for walls and attics, need high-performance lighting or require tankless water heaters, among other items. And inspections for compliance will be, at least in the near term, the most important tool for advancing the energy-efficiency goals.

Homeowners, however, are less than assiduous about getting permits even when they are required: The energy commission estimates that 90 percent of residential heating and cooling upgrades, for example, are performed without official permission.

Enforcement is easier for work performed on large commercial structures, which is more likely to come to the attention of inspectors and can incur heavy violation penalties. And businesses are worried.

Matthew Hargrove, Senior Vice President of governmental affairs at the California Business Properties Assn., represents owners of commercial buildings, who are concerned about the cost of upgrades. He said the last code update, in 2014, required advancements that tripled the cost of redoing lighting systems.

The mandate seemed simple enough, he said, but “we had lighting contractors saying the requirements were so expensive that their businesses died on the vine” when many building owners chose not to upgrade.

Refurbishing buildings that have modern, more efficient infrastructures may be relatively affordable, but those structures are poor candidates to reap significant energy savings, Hargrove said.

The real savings are to be found in older commercial buildings, but those are often held by owners who can least afford upgrades, Hargrove said. When a commercial building erected in the 1920s or 1930s requires major work, the cost of bringing it to code may be prohibitive.

Despite the unknowns, it seems certain that maximum residential efficiency will come with some sticker shock for homeowners. Estimates vary dramatically, depending on the extent of efficiency.

Jacob Atalla is Vice President of Sustainability for KB Home, which is building the technologicallysophisticated houses in El Dorado Hills. He said the systems in those structures save about $3,948 annually in utility expenses. But the price tag for those houses runs about $50,000 more than for homes without so many energy-saving bells and whistles.

The energy commission, however, estimates it will cost only an additional $2,700 for a new home to simply meet the building code taking effect Jan. 1. The agency estimates that over the life of a 30-year mortgage, those code requirements would save a homeowner $7,400 in energy and maintenance expenses.

However, a commission report last year acknowledged that most Californians stay in homes only five to eight years and “may not recoup the value of a deep retrofit project while they own the home.”

Officials point out there are ways to soften the blow. Utility companies currently offer $1 billion a year for programs, some funded by their customers, to encourage energy efficiency. Major utilities and state agencies offer rebates for homeowners who upgrade, and myriad programs help low-income families use less energy.

In addition, state funds have been set aside to help aging schools upgrade. Schools spent $300 million last year on such improvements as newer windows and modern heating and cooling systems.

Nonetheless, there is concern that the burden of complying with the requirements will fall heavily on the poorest Californians. Nearly a third of the state’s utility customers are categorized as low-income, according to the Public Utilities Commission.

They currently receive about $30 million a year in federal weatherproofing assistance, according to the Public Utilities Commission. But they may need more.

“It’s important that sustainability not be defined just in terms of environmental sustainability, but equality and income sustainability,” said Tyson Slocum, director of the energy program at Public Citizen, the non-partisan public interest group. “Cost can’t be a barrier to participate.”

Proponents note that as technology evolves, it gets less expensive. A 2015 state report envisions an $8 billion annual private-sector efficiency marketplace, in which technology companies innovate with products and services to make energy savings reachable for more people.

State officials vow that California will find a way to slash its energy footprint as it educates residents about how, and why, to do so.

“Part of the challenge is a relatively basic education, so that people can understand what their actions imply in terms of energy consumption,” McAllister said.

“The conditions are absolutely there to achieve our goals,” said, “We can do it.”

Correction: An earlier version of this article cited Jacob Atalla, Vice President of Sustainability for KB Home builders, as saying the company’s technologically sophisticated houses could save residents about $1,000 a year in utility bills. He was actually referring to KB’s standard new homes. The company estimates that its most energy-efficient homes would cut utility bills by $3,948 annually, assuming moderate consumption. That number would vary according to local utility rates and other factors, and it excludes taxes and fees.

See more stories on building efficiency.

Cross-posted on CALmatters.