Here are four reasons why Californians – and everyone else in America who breathes oxygen – should be alarmed that Scott Pruitt, the Trump Administration’s nominee to become EPA secretary, testified last week he may not grant waivers for California to exercise its authority under the federal Clean Act to enact air quality regulations that are more stringent than those of the federal government:

- Los Angeles.

- Bakersfield.

- Visalia.

- Fresno.

These California cities rank as the top four U.S cities with the worst air quality.

The reason that Congress, back in 1970, granted California authority to go beyond federal standards is that California had the worst air pollution in the nation. It had already taken aggressive action in 1967 under Gov. Ronald Reagan to address the persistent smog that was choking the Los Angeles Basin, regularly triggering red-flag alert days in which schoolchildren were forbidden from playing outside.

The caveat was that the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency would review any California regulations that exceeded federal standards and grant a waiver to allow such regulations to proceed. These waivers, dozens of them, were granted routinely for decades, and were responsible for some of the nation’s most important environmental health advances – catalytic converters in car engines, for instance, or vapor-trapping nozzles on gas pumps.

With California and its Air Resources Board driving such technological advances, the air got cleaner – still unhealthy much of the time, but cleaner. The San Gabriel Mountains reappeared on the Los Angeles horizon, and red-flag days at public schools went the way of the school-based nuclear fallout shelters that had proliferated during the Cold War.

Other states took notice. Once a waiver had been granted, federal law gave other states the option of adopting the more rigorous California standards. Many did exactly that. Their air got cleaner, too.

It was not until 2002, when California passed its Clean Car Law, mandating a reduction in greenhouse gas emissions from automobile tailpipes, that the waiver process became political, rather than administrative. President George W. Bush’s Administration denied the waiver, putting California and 13 other states that sought to follow its lead on hold.

The momentum swung in 2007, when the U.S. Supreme Court ruled in Massachusetts v. EPA that greenhouse gas emissions could be regulated in the same manner as air pollutants that cause direct harm to human health. Then, two weeks into his presidency in 2009, President Obama announced the waiver denial would be reviewed, leading to a reversal of the Bush Administration’s decision.

The end result: New, nationwide fuel-efficiency standards for cars that will have the effect of reducing climate pollution by more than 500 million metric tons by 2030. The not-at-all incidental co-benefit will be their effect on preventing unhealthy pollutants from reaching Americans’ lungs – the equivalent benefit of shutting own 240 coal-fired power plants.

Pruitt, the attorney general of Oklahoma, made his remarks on the same day it was announced that 2016 marked the third consecutive year in which the planet recorded its hottest year on record. He is unlikely to be swayed by arguments that California’s special status under the Clean Air Act should be maintained for the sake of combatting global warming.

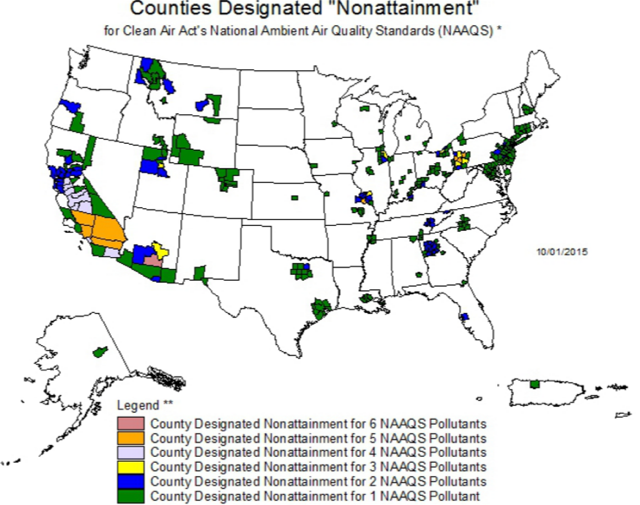

Instead, the point must be made that California’s unique ability to lead on policies to reduce air pollution protects children’s lungs – not just in Los Angeles and Fresno, but also in cities further down on the worst-air-quality list. Places like Pittsburgh and Cleveland, St. Louis and Tulsa, Dallas and Indianapolis.

The people in those cities have benefited from clean-air waivers granted California over five decades. They may not all share the commitment of Californians to address climate change, but they care just as much as a parent in Bakersfield when their kids develop asthma.