The burgeoning political standoff between California and the Trump administration took another step into unprecedented terrain this week when, on a pre-Super Bowl televised interview, the President denounced California as “out of control” and contemplated cutting its federal funding. The threat came in response to moves by the Democratic-controlled Legislature toward providing additional legal protections for undocumented immigrants and labeling California itself a “sanctuary state.”

But with President Donald Trump issuing an executive order to defund sanctuary jurisdictions, and San Francisco suing to have the order declared unconstitutional, a number of questions remain—not the least of which is “can the President really defund an entire state?”

Here’s what we know, and what we don’t know:

1– “Sanctuary” is not an official designation

Despite all the controversy, there is no single definition of what a sanctuary jurisdiction actually is.

Broadly speaking, a city, county, or state is considered to have sanctuary status if it puts some restrictions on the degree to which its law enforcement officials can enforce immigration law. Opponents call this obstruction of federal law; sanctuary city defenders counter that it’s not the job of state and local police to enforce federal immigration law.

Still, sanctuary cities run the gamut. The label certainly applies to San Francisco, which prohibits municipal employees from using “any city funds or resources to assist in the enforcement of federal immigration law or to gather or disseminate information regarding release status of individuals.” But depending on whom you ask, the “sanctuary” designation might also apply to a place like Sonoma County, which merely maintains an unwritten rule that sheriffs’ deputies not go out of their way to inquire about, or act upon, immigration status.

According to some, the entire state of California fits the bill.

The state’s Trust Act from 2013 prohibits state and local law enforcement officers from keeping non-felons in custody solely at the request of Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE). For example, if an undocumented immigrant is arrested for driving under the influence, the county jail can only keep that person for that offense—regardless of any ICE detainers.

2– President Trump defines “sanctuary” status by whether police are allowed to communicate with ICE

The President’s executive order to defund “sanctuary jurisdictions” defines them in a surprisingly precise way—citing Title 8, section 1373 of the U.S. Code, which states that no law can “prohibit or restrict” the sending and receiving of information about citizenship or immigration between local, state, or federal government officials and ICE.

Advocates for tougher immigration enforcement see San Francisco’s sanctuary city policies as a clear violation of that law.

But in its lawsuit filed in response to the executive order, the city argues that its policy doesn’t prohibit police from communicating directly with ICE about immigration and citizenship status—it just doesn’t allow them to use city resources to do so. In other words, for instance, the law doesn’t prohibit a police officer from calling ICE on his or her own phone.

California Senate Democrats appear to agree. In early December, Senate President Pro Tem Kevin de León (D-Los Angeles) introduced SB 54, which would similarly prohibit state and local government employees across California from using public funds to cooperate with ICE investigations. The bill, which de León calls the “California Values Act,” has already started sailing through committees with party-line approval.

Whether SB 54 will make California a sanctuary state in the eyes of the federal government—or whether it already enjoys that status thanks to the Trust Act—is not yet clear. Trump’s executive order tells the Attorney General and the Secretary of the Department of Homeland Security to define which localities are sanctuary scofflaws. That ambiguity has some city officials worried: Miami-Dade Mayor Carlos Giménez, for example, responded to the executive order by directing county officials to comply with all detainer requests from ICE.

3– Police are split over sanctuary status

Why would some law enforcement agencies support it? First, enforcing immigration law requires time and resources.

“Most immigration offenses are not criminal, they are civil violations, and cops don’t really worry about civil violations,” says Jessica Saunders, a criminologist at the nonprofit RAND Corporation think tank. ” If we’re adding this additional responsibility for them, do they have the capacity to do it? Is it actually going to help their primary mission of fighting crime?”

Local police also say it’s important to maintain the trust of the policed. In response to the executive order, the Major Cities Chiefs Association, a professional group of police chiefs and county sheriffs, expressed concern that requiring police to enforce immigration law might discourage members of the immigrant community from seeking out law enforcement when they need help.

“Immigrants residing in our cities must be able to trust the police and all of city government,” the association said.

Finally, some police departments also worry about legal liability. In 2011, the Sonoma County Sheriff’s Department settled allegations that it had racially profiled people and engaged in unlawful detention in the course of assisting ICE investigations. (Interestingly the settlement had the sheriff’s department adopt new policies that might very well make it a “sanctuary jurisdiction” in the eyes of the Trump administration. Namely: suspected unlawful immigration status isn’t enough to justify investigating or detaining someone, and cooperation with ICE can only take place under restricted circumstances.)

Still, police opinion is split. The National Fraternal Order of Police issued a statement in favor of the President’s executive order, and the California State Sheriffs Association has come out against SB 54, stressing “the need for law enforcement to be able to work together at all levels of government.”

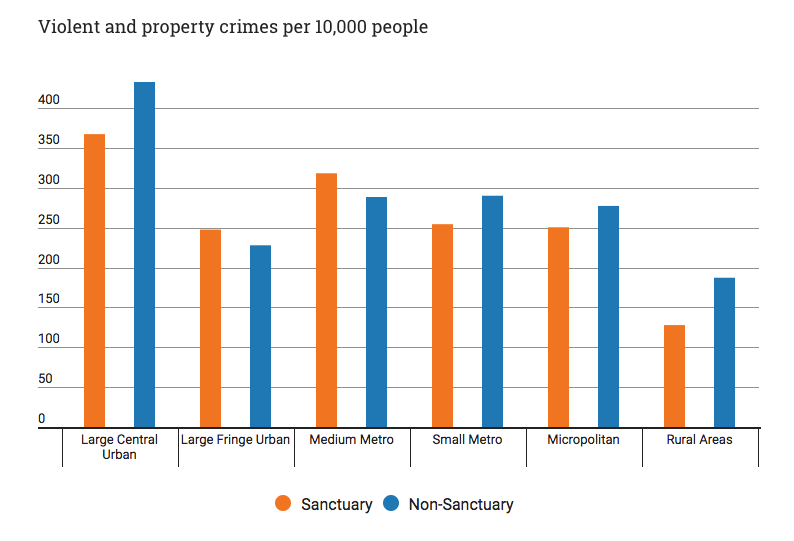

Crime tends to be lower in sanctuary counties

While police officers may differ over whether sanctuary policies make their jobs more or less difficult, there isn’t much evidence that it leads to higher crime. A recent study by the University of California, San Diego political science professor Tom K. Wong concluded that crime is significantly lower in sanctuary cities and counties. That doesn’t mean that sanctuary policies lead to lower crime (sanctuary cities also tend to be more affluent, which could influence the crime rate), but it seems to contradict the claim made by President Trump that sanctuary cities “breed crime.”

4– California’s best defense against the executive order may be “state’s rights”

San Francisco City Attorney Dennis Herrera insists that his city’s policies do not violate Section 1373. But even if they did, he argues in a complaint submitted to the U.S. District Court, section 1373 is “unconstitutional on its face.”

Because the law dictates how local and state employees can or cannot communicate with ICE, the city contends that it constitutes the commandeering of state and local officers by the federal government, and therefore violates the 10th Amendment of the Constitution.

Legal wonks may note the irony here. The 10th Amendment provides that “powers not delegated to the United States by the Constitution, nor prohibited by it to the States, are reserved to the States” and is the foundation of many “states’ rights” arguments typically favored by small-government conservatives. Call this San Francisco’s “Born Again Federalist” moment.

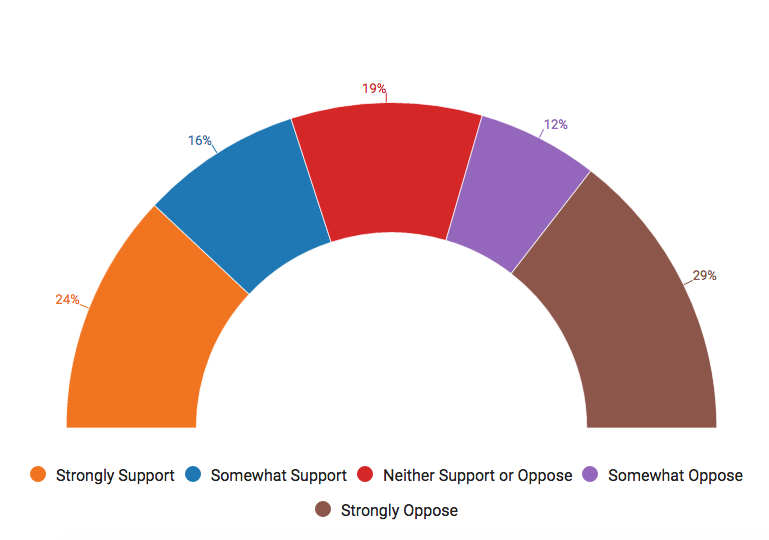

Californians split on support for sanctuary status

In fact, according to some legal scholars, San Francisco’s best line of defense might come from a 1997 Supreme Court case over the Brady Handgun Violence Prevention Act, which would have required local police and sheriffs to perform background checks on prospective gun buyers. The Court struck that provision down on 10th Amendment grounds.

The majority opinion, written by the late Justice and titan of conservative jurisprudence Antonin Scalia, held that the federal government simply cannot “command the States’ officers, or those of their political subdivisions, to administer or enforce a federal regulatory program”

According to Deep Gulasekaram, a professor of constitutional and immigration law at Santa Clara University, that argument looks an awful lot like the question over sanctuary cities.

“If you apply that same logic there, Congress cannot force local law enforcement officers to participate in immigration enforcement,” he says. “They simply can’t.”

Still, this won’t be the first time that Section 1373 sees its day in court. In 1999, New York City saw its own policy, which banned city employees from passing information about undocumented immigrants to federal immigration authorities, struck down by a federal court as a violation of the statute.

San Francisco is now hoping that a court will either view the city’s own sanctuary policy as narrower than New York’s blanket ban on communication—or better yet, that the New York ruling will simply be overturned.

5– If Trump tries to strip sanctuaries of federal funding, it won’t be that easy

California’s Legislative Analyst’s Office recently estimated that California receives roughly $368 billion from the federal government every year. That includes $79 billion in direct spending to the state, $8.2 billion in local and county funding, and $281 billion to California-based individuals, non-profits, businesses, and universities. (It might be worth noting that this is still substantially less than the $405 billion that the federal government collects from California, but so far, no California lawmakers are threatening to cut off D.C. in retaliation and, even if they did, it isn’t clear how the state would go about doing that).

Now that the Trump administration has threatened to pull federal funding from sanctuary jurisdictions, how much of this money is actually on the line?

Where do California’s federal dollars go?

Courts have traditionally limited the degree to which the federal government can use funding as a cudgel against uncooperative state and local governments.

First, most legal scholars agree that the money at stake generally has to relate in some way to the law or action that the federal government wants the city or state to take. For example, in 2016, California received a total of $132 million in grant money from the Department of Justice’s Office of Justice Programs. While the Trump administration might be able to pull those funds in response to the state’s sanctuary policies without too much legal trouble, cutting off the entire $368 billion tap might not pass constitutional muster.

Likewise, courts have generally held that conditions on federal grants have to be spelled out to recipients ahead of time. This prevents the federal government from luring a city or state into taking federal funding only to use those dollars as ransom to extract desired policy changes.

Lastly, and maybe most challenging for the Trump administration’s de-funding efforts, courts have ruled that federal funding options can’t be so coercive that they pass the point where “pressure turns into compulsion” and they deprive local or state governments of any real choice about policy decisions.

For example, the federal government makes a small fraction of highway funding contingent on each state maintaining a legal drinking age of 21. The Supreme Court has held that this restriction wasn’t unduly coercive because of the relatively small stakes involved. But what about a threat to take away all federal funding?

Through his executive orders and in other ways, President Trump is likely to test the limits of these precedents. After a recent protest turned violent at UC Berkeley, he took to Twitter, asking whether the university couldn’t also be deprived of federal funding.

“I don’t have a crystal ball, so maybe a court looking at this would end up changing the way we understand these conditions,” says Santa Clara’s Gulasekaram. “But the fact is, that’s not how constitutional law works.”