Last month Detroit mayor Mike Duggan claimed he had been kept in the dark about calculations used during Detroit’s 2014 bankruptcy proceedings to predict future pension payments. Realizing now that payments will be much higher than projected, the mayor is considering a lawsuit because “we did not know that [the projections] were based on optimistic criteria.”

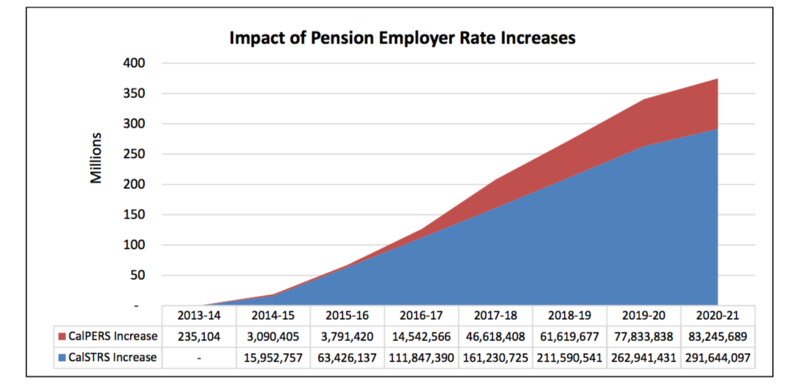

That same year California imposed a steep pension cost increase on school districts to fund a bailout of the teachers’ pension fund (CalSTRS) and to meet unfunded liabilities at the state’s other pension fund (CalPERS). The cost of the increase to the Los Angeles Unified School District (LAUSD), California’s largest school system, was projected as follows:

LAUSD, 2015 Report of the Independent Financial Review Panel

However, those projections are based on unrealistically optimistic assumptions that CalSTRS and CalPERS will earn investment returns exceeding 20th century returns for similar portfolios by more than 20 percent. Like Detroit, LAUSD will likely face steeper payments in the future, as explained here. That will leave even less money for classrooms and young teachers.

In his book Capital in the 21st Century, French economist Thomas Piketty writes about financial obligations “devouring the future.” In LAUSD’s case, the futures being devoured belong to students and young teachers who, because of fast-growing district spending on past pension obligations, are being denied well-staffed classrooms and salaries that allow teachers to live decent lives in the communities they serve.

It didn’t have to be this way. Defined benefit plans work just fine when properly managed. It will take great leadership at LAUSD and other school districts to address the consequences of improper management.