“When I see someone attacking the benefits the Fire Department receives or the Police Department receives, my concern is: Why wouldn’t you expect the same for yourself? We should act as a beacon.”

—Mike Mohun, president of the San Ramon Firefighters Union, quoted in the New York Times, March 2, 2017

There are many compelling reasons to examine this statement by Mr. Mohun, since pension benefits for state and local government workers are consuming ever increasing percentages of tax revenue. For starters, using the term “attack” is unfair. More accurate might be “counter-attack,” since the costs for these pensions are what has become extreme, not our reaction. If these pensions were financially sustainable, California’s citizens would not be under attack by continuously escalating taxes, and continuously diminishing public services.

But why shouldn’t we expect the same for ourselves? This doesn’t seem like an unreasonable statement. Perhaps to evaluate the reasonableness of Mohan’s idea, let’s examine the benefits received by retirees in the San Ramon Valley Fire District.

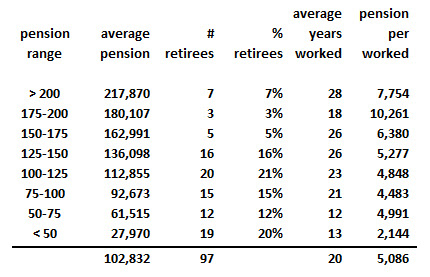

According to Transparent California, there are 97 retirees who used to work for the San Ramon Valley Fire District for whom years of service were disclosed. As can be seen in the table below, 7% of these retirees are collecting a pension in excess of $200K per year, based on an average years of service of 28 years. Three more, 3%, collect a pension over $175K per year, based on average years working of 18 years. Without recapping the entire body of data, note that more than half the retirees collect pensions over $100K per year. The average pension for all retirees is $102,832 based on an average of 20 years of service.

Contra Costa County Pension System – San Ramon Valley Fire District

Retiree Pension Data, 2015

What’s not in these numbers is significant, if we really wish to understand what Mr. Mohun is suggesting we all should expect for our retirements. These averages are skewed lower than the reality because (1) some of the retirees appear to have been administrative or part-time employees, not full-time firefighters, (2) some of them probably bought “air-time” at bargain-basement (probably financed) rates which inaccurately distorts upwards their years of service, and (3) it is likely that all of them are collecting other supplemental retirement benefits such as retiree health care which usually adds at least $10K per year to the cost of their retirement benefit.

So Mr. Mohan is certainly not suggesting that we all retire after 20 years of work with a $100,000 pension, is he? Let’s further explore this.

There are 7.0 million Californian’s over the age of 60, but after all, if we only work for 20 years, that means we’ll be retiring well before we turn 60. To accurately predict how we might quantify the macroeconomic impact of Mr. Mohun’s expectations for us all, we’ll need to consider how many Californians are over the age of 45. That retirement age would be based on the assumption that once we’ve completed an extended period of education and life experience, we begin full-time work at the age of 25, and retire when we’re 45 with a $100K pension for the rest of our life. There are 20 million Californians over the age of 45 in California.

Implementing the Mohan plan, therefore, would cost $2.0 trillion per year. Perfect! That’s still a bit less than California’s entire GDP of 2.5 trillion!

There’s a snag in all of this, however, because if you allocate 80% of California’s GDP to pay retirees, it only leaves a half-trillion to pay the workforce – those Californians between the ages of 25 and 45. There’s 10 million of them (actually 11.3 million but we’re rounding), so they would only be able to make $50,000 per year. And of course, no money would be left over for anyone under the age of 25 who might be trying to work their way through college.

Snags abound. What might it take to finance a pension of this magnitude? Wouldn’t this money have to be set aside? To get an idea, let’s see just how much is being set aside each year for Mr. Mohan and his cohorts in the San Ramon Fire Protection District.

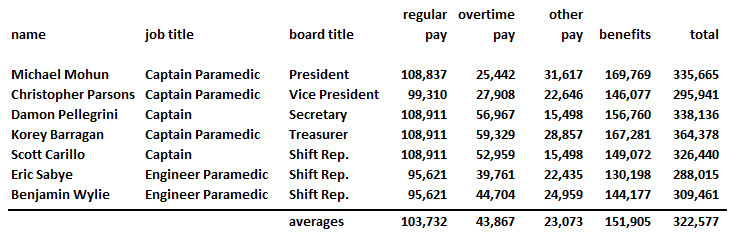

For this we have to refer first to the webpage of the San Ramon Valley Firefighters Local 3516 that reveals their board members. Cross referencing these names with data from Transparent California yields the following information:

San Ramon Firefighters Local 3515 Board Members

As can be seen in the second to last column on the right, “benefits,” taxpayers are setting aside, on average, $151,905 per year to pre-fund retirement benefits for Mohan and his fellow union board members. The payments being made to their pension system are roughly equal to their entire annual pay, including overtime and “other pay.”

In a recent California Policy Center study entitled “California’s Public Sector Compensation Trends,” the average pay and benefits for a private sector worker in California in 2015 was estimated at $54,326. Unlike public safety averages, this $54,326 estimate undoubtedly exceeds the median, and, overall, was arrived at using generous assumptions. The reality is lower, not higher.

It is accurate to say that a San Ramon Valley Firefighter can expect to work half as many years as the average Californian in exchange for twice as much in pay – then retire 20 years earlier and collect a pension roughly four times (or more) than the average retirement income of the average Californian. Granted, firefighters should make more than the average worker. But over a lifetime, six times as much?

One final note: “Attacking” levels of compensation that are financially unsustainable and unfair to taxpayers does NOT translate into an attack on the profession of firefighting or firefighters as individuals. No reasonable person fails to respect firefighters for the work they do and the risks they take. But if and when the market takes another dive, and even before that, Mr. Mohan and his colleagues are invited to think about proposals that are not merely inspirational for everyone, but practical.

They might begin by recognizing how California’s legislature has enacted policies which make this the highest cost-of-living state in the U.S. They might use their considerable political clout do help us do something about that – for everyone’ssake.

Ed Ring is the vice president of the California Policy Center.