With President Donald Trump alleging serious voter fraud in California, and the state’s top election official calling his claim untrue, how much voter fraud is actually under investigation in the Golden State?

Not much—certainly not enough to sway the election, in which California voters chose Hillary Clinton over Trump by 4.3 million votes.

And while the California Secretary of State is investigating some cases of potential fraud, not a single case opened last year involves allegations of voting by an immigrant who is in the country illegally—a stark contrast to the picture painted by Trump.

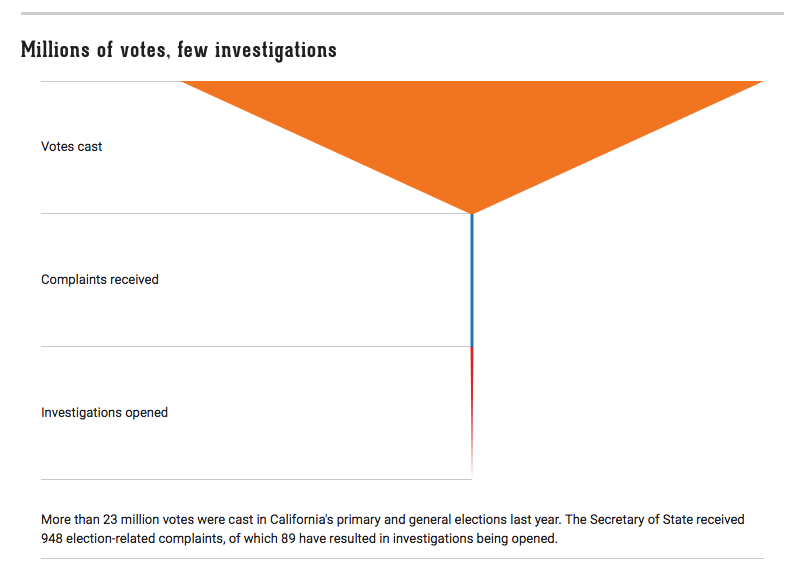

The Secretary of State received 948 election-related complaints in 2016, according to its response to a CALmatters’ Public Records Act request. The office determined that more than half (525) did not merit criminal investigation. Of the remaining complaints, 140 are still being screened, 194 were non-criminal problems referred to local officials, and 89 triggered investigations by the Secretary of State.

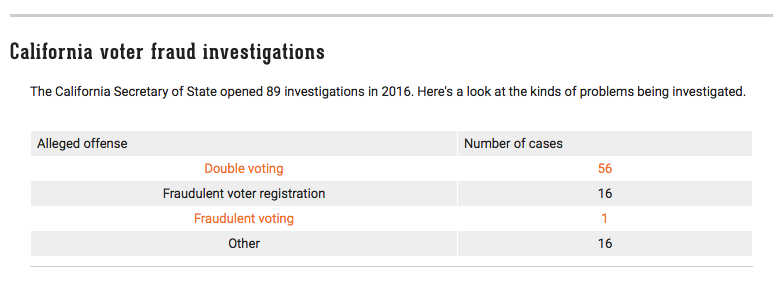

The office did not provide details on the 194 cases it sent to local authorities. But of the 89 investigations the Secretary of State opened in 2016: 56 are allegations of double voting, 16 are allegations of fraudulent voter registration and 1 is an alleged case of fraudulent voting. The rest allege wrongdoing by candidates, petition circulators and others who work in the elections arena – not by voters themselves.

Together, the cases the Secretary of State is investigating and those it referred to counties amount to one one-thousandth of one percent (0.001%) of the more than 23 million votes cast in California’s primary and general elections last year.

The miniscule number “undercounts the amount of potential fraud because a lot of it would not be reported,” said Richard Hasen, a professor of election law at the University of California, Irvine. It also doesn’t include investigations that could be underway if initiated by prosecutors in the state’s 58 counties.

Still, Hasen said, “I see no evidence that voter fraud is a major problem in California.”

He cited an exhaustive study that found just 56 cases of election fraud in California between 2000 and 2012, most of it perpetrated by campaign officials, not voters. The view held by Hasen and supported by many academic studies conflicts with claims by Trump, who has been complaining about fraudulent voting for months, without citing evidence of a widespread problem.

In November, Trump tweeted that “the millions of people who voted illegally” had cost him the popular vote, and that there was “serious voter fraud in Virginia, New Hampshire and California.” He repeated similar claims in a meeting with Congressional leaders in January, and then announced in February that he would put Vice President Mike Pence in charge of investigating voter fraud. Pence is forming a task force to do the investigation, though a recent poll found that only 1 in 4 voters believe Trump’s claims.

“The burden is on the president and his team to bring forward proof or evidence,” said Secretary of State Alex Padilla, a Democrat. “We’ve been asking them for it since November and they’ve had nothing to show.”

There are no signs yet that the White House investigation has begun. No one from Pence’s task force has contacted the California Secretary of State’s office, said Padilla spokesman Sam Mahood.

In response to the records request, the Secretary of State’s office would not provide copies of the complaints it received last year, saying they are exempt from disclosure. It did provide tallies of the number of complaints and the categories of potential violations of those that are being investigated.

Republican state Sen. Joel Anderson of Alpine, a Trump delegate who is vice chairman of the Senate’s elections committee, said he’s seen signs of fraud while campaigning in his San Diego-area district. He’s encountered houses where a registered voter—marked as voting in the last several elections—turned out to have been dead for years, and empty lots carrying addresses where people are registered to vote.

“All you have to do is walk a precinct and you know there is fraud,” said Anderson. “The question is: Is it rampant? Is it rare? We don’t know.”

But when told of the small number of voter fraud complaints tallied by the Secretary of State, Anderson called the figures “spectacular.” He said if the White House audit similarly finds an insignificant number of problems in California, Padilla deserves a gold star.

“If those are the numbers and those hold true, that’s a phenomenal job. We should hold up those numbers to 49 other states.”

While Trump claims that large numbers of people in the country illegally are voting, past prosecutions in California include few cases of voting by non-citizens. In 2012, an unauthorized immigrant in Escondido pleaded guilty to voting illegally in the 2008 presidential election by using the name of a U.S. citizen. In 2008, a man was sentenced to jail in Orange County for registering two under-age teenagers and a non-citizen to vote. In a more high-profile case in 1996, Congress opened an investigation after a Republican congressman from Orange County argued that voting by non-citizens had caused him to lose re-election—but the investigation was eventually dropped.

Instead, election crimes prosecuted in California more typically involve wrongdoing by political candidates and public officials. In recent years, a state senator from Inglewood, an Escondido school board member, the former mayor of Vernon and the manager of a community services district near Redding were convicted of voter fraud for lying about their address. City officials in the Southern California city of Cudahy pleaded guilty to tampering with ballots to favor incumbent city council members and discard votes for challengers.

Some Trump supporters have said it would be easy for undocumented immigrants to vote in California because of two state laws approved in recent years. A bill passed in 2013 allows undocumented immigrants to get driver’s licenses. And a bill passed in 2015 creates a system to automatically register people to vote when they get a driver’s license.

But the notion that these two laws have filled California voter rolls with undocumented immigrants is false. The automatic registration process allowed by the new law has not yet gone into effect. Padilla said he expects it to roll out this summer, with a protocol he’s certain won’t allow undocumented immigrants to register to vote.