Tax reform may not be much more than a glimmer in the eye of Republicans in Washington D.C., but their promise of lower rates and closed loopholes appears to be already jostling state and local finances.

Exhibit One comes in the form of a disappointing haul for California tax collectors this summer. In June, the most recent month for which figures were available, the state took in $361 million less than lawmakers planned for in the state budget.

While there are plenty of reasons for revenues to miss their projected mark—an unexpected economic cold snap, perhaps, or a forecasting model miss—the fiscal sleuths at the Legislative Analyst’s Office suggest that something else could be afoot. They wrote in a recent report that “high-income taxpayers may be deferring income and/or tax payments to late 2017 or even 2018 in anticipation of a federal tax cut.”

It’s a phenomenon that may be sweeping the nation: States such as New York and Massachusetts, both of which levy state income taxes, report lackluster receipts.

The evidence for California is incomplete, but compelling.

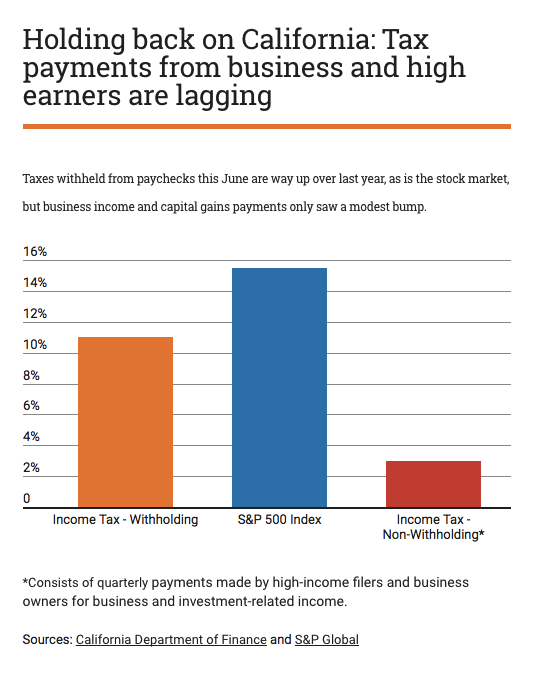

For one, state sales taxes actually came in higher than expected. So did withholding receipts—the money that gets taken out of your paycheck. That rules out the possibility that the state economy has taken an unexpected dip.

What came in under expectations are the estimated payments, made four times per year, that high-earners pay on income from capital gains, businesses, interest payments, and dividends. Corporate tax payments also came in below the forecast.

More importantly, says Justin Garosi, an economist at the Legislative Analyst’s Office and one of the authors of last month’s report, estimated payments are only up 3 percent since last June, despite the S&P 500 stock index booming over 15 percent over the same period. Corporate America and Wall Street have had a blowout year, so where are their tax payments to prove it?

“For wages and salaries, it is generally not possible to have your employer delay a paycheck so it gets recorded in 2017 instead of 2016,” said Garosi. But those who earn a living by, say, selling stocks, often have the luxury of picking their payday.

These taxpayers also have the option to simply fork over whatever they paid last year as an estimate on current earnings and then make up the difference later, explains Garosi.

“The puzzle we were talking about is that stock prices are up big over last year, but estimated payments aren’t,” he said. “This suggests that a lot of people are paying what they paid last year even though they expect to eventually have more liability in 2017 than in 2016.”

One reason to do that: you expect to pay a lower tax rate next April.

It’s still too early to say whether that’s exactly what’s going on. The state’s high earners may be holding off on cashing out this year’s bull market for a variety of reasons. More detailed information— about which types of taxes are being paid by which groups, and when—won’t be available until at least 2018. “Even if we did have complete data on capital gains income, we couldn’t be certain how much the level of gains was affected by expectations of federal tax changes,” said state Finance Department spokesperson H.D. Palmer.

But what’s clear is that the stock market is soaring and estimated payments are not, a trend that “would support the notion” that deferral is taking place, he said.

This wouldn’t be the first time this year that the premonition of lower taxes has been blamed for throwing a wrench into California finances. When it comes to taxes, expectations can be just as important as reality.

In the weeks after the election, the market for California municipal bonds, which are tax-exempt and fund most local development projects, took a dip. Some investment experts saw this as a sign that—with possible tax cuts on the horizon— the appeal of low-return but tax-free investments had worn thin. Prices have since come back up, but may dive back down if Congress gets serious about tax reform.

Similarly, affordable housing developers across the state began complaining earlier this year that they were having a harder time raising cash from investors. These projects often are supported by the state’s Low Income Housing Tax Credit program, which allows banks and other big investors that put money into below-market housing projects to write off a portion of their tax bill.

But the election had a profound effect on the state housing market, said Matt Schwartz, president of the California Housing Partnership Corporation, a state-created nonprofit that provides financial and policy consulting on affordable housing issues. He said in deals the corporation helped oversee or advise, within a few weeks of the election prices dropped by more than 25 cents per dollar of credit. Investors indicated a diminished appetite for tax-saving investments.

Those prices have since come back up, but only slightly. He said offers are still 10 to 15 percent below the pre-election high.

“We know of at least $10 million (worth of projects) where local governments pretty much had a gun put to their head and told that they had to step up or hundreds of homes ready to start construction would just fall apart,” he said. “Every one of those lost percentage points is huge in terms of how many fewer affordable rental homes will get produced.”

But investors can only make the argument that tax reform is on the way for so long. Nearly seven months into the current term, Congress has been short on major legislative accomplishments—a fact highlighted by its failure to repeal the Affordable Care Act last month. Rewriting the tax code, or just cutting top rates, can’t be done overnight.

But for the state’s finances, the future may be bright. If in fact high earners have been holding back on the hope of a friendlier tax code, the good news for the state is that these taxpayers can’t kick the can forever. “As high-income tax filers eventually take gains from investments and businesses and make delayed tax payments, these eventually would show up in state revenue collections,” wrote the Legislative Analyst’s Office.

No matter what happens in Washington D.C., the state of California could see a big payday next April.