Inside the California Assembly chamber on the night of June 1, the presiding officer urged lawmakers to recognize former members in their midst, “the honorable Henry Perea and Felipe Fuentes.” In a familiar Capitol ritual, the former assemblymen waved from the balcony as applause rang out from their one-time colleagues.

But the two weren’t just retired lawmakers—they were now lobbyists being paid by oil companies to kill a bill that would soon meet its fate on the Assembly floor below.

That bill, by Democratic Assemblywoman Cristina Garcia, aimed to force industry to reduce air pollution that comes from their plants. Garcia knew the lobbyists in the balcony were pals with many of her Assembly colleagues, she knew oil and other industries were working hard to defeat her, and she knew her bill was in danger.

A million people in her industrial Los Angeles neighborhood “have been treated like a wasteland,” Garcia said in frustration, wiping tears from her eyes. Then she cast a glance toward the balcony. “Clean air is a big deal for a lot of Californians,” she said. “You have a choice: Do we all matter?”

Her bill fell six votes short, as moderate Democrats joined Republicans to quash it. The moment marked a win for oil—and revolving-door politics.

Today Garcia cites the lobbyists’ special relationships with current legislators as among the factorsto blame for her bill’s demise. “When you have a former member on the floor at the same time they are working for or against the bill,” she said, “you open the opportunity to have access in a way lobbyists normally would not have.”

Sacramento is full of termed-out or retired lawmakers who make second careers as lobbyists, strolling through a “revolving door” between government and the private sector. Current law prohibits ex-legislators from directly lobbying their former colleagues for one year after they leave the Legislature, and a measure on Gov. Jerry Brown’s desk would slightly strengthen that by barring legislators who quit mid-term from lobbying during the remainder of that two-year-session, plus another year.

Still, the oil industry’s strategy this year was striking. After failing last year to prevent a new law requiring massive cuts to greenhouse gas emissions, oil came back this year lobbying hard. Now Democrats held a supermajority in the Legislature but were divided over how to redesign the state’s landmark cap-and-trade program, which forces businesses to reduce emissions or pay for permits to pollute.

The oil industry’s goal: to shape the next phase of cap and trade through 2030. And it had hired four former lawmakers—all Democrats—to advocate on its behalf.

Each hailed from predominantly working class, Latino districts and joined an influential “mod squad” of moderates during their legislative tenures, which covered various periods between 2002 and 2015. Two are from Kern County, the biggest oil producer in California. And three quit their elective office mid-term to work for industry.

All four declined interviews for this article, as did their employers. Three were registered lobbyists during the peak of cap and trade negotiations this year:

- Henry Perea, the son of a Fresno city councilman and grandson of Mexican immigrants, made his mark in the Assembly as the former leader of its mod caucus before quitting mid-term, initially to work for a pharmaceutical trade association. Now he lobbies for the Western States Petroleum Association.

- Felipe Fuentes, raised in the San Fernando Valley, worked as a legislator to secure tax credits to keep filmmakers in the state, then was named to the Los Angeles Times 2016 “naughty” listfor bailing on his LA city council seat to become a lobbyist. His firm’s clients include an oil production company.

- Michael Rubio, who worked his way up in Kern County politics, abruptly quit the state Senate in 2013 to work for Chevron, saying he wanted to spend more time with his family.

A fourth is not a registered lobbyist, but manages government affairs for a refinery company:

- Nicole Parra, whose father was a Kern County Supervisor, won election to the Assembly at age 32 and also became a mod caucus leader, known for sometimes endorsing Republicans.

“The industry showed incredible smarts by going out and hiring these people. Nationally, the oil industry is very Republican,” said David Townsend, a Democratic political consultant who knows all four through his work running a fundraising committee that helps elect business-friendly Democrats.

“Their knowledge base is enormous. Their relationships are broad-based and deep. If I were in trouble, they are some of the ones I’d hire,” Townsend said.

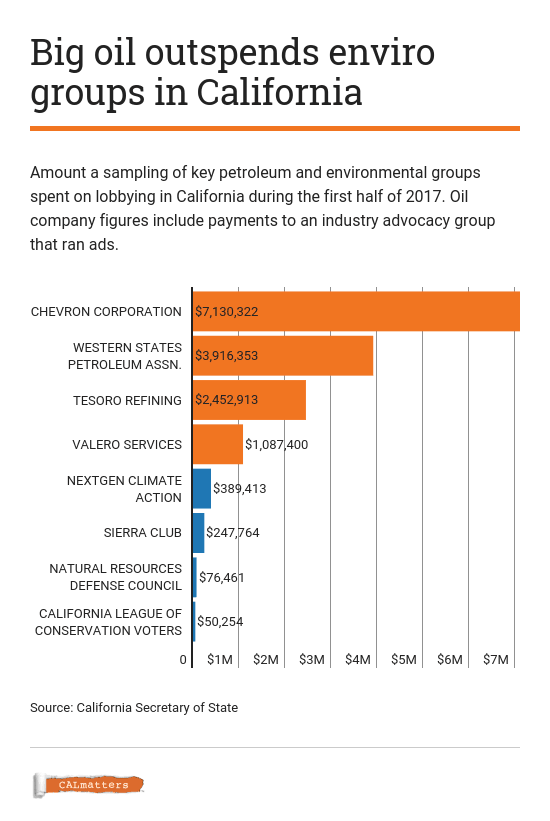

Oil companies have a long history of fighting against the aggressive climate policies backed by many California Democrats. This year, though, instead of fighting against cap and trade, oil teamed with other business interests to lobby to make cap and trade more industry-friendly. In the final deal that lawmakers approved on a bipartisan vote in July, oil won a new law forbidding local air quality districts from enacting emissions restrictions tighter than the state’s—as well as a potential perk worth hundreds of millions of dollars. Leading environmental groups supported the bill to extend cap and trade for another decade, but other environmentalists wound up opposing it for being too easy on polluters.

“This easy crossing from legislator to advocate for the industry has happened before, but it seems to have been happening recently in greater bulk. So that, to me, is kind of distressing,” said Kathryn Phillips, a lobbyist for the Sierra Club, which opposed the cap-and-trade plan.

“These are people who have been friends with the people they are going to lobby.”

Many aspects of those relationships play out in ways the public never sees—through text messages, phone calls or at private get-togethers. Weeks before lawmakers voted on the final cap-and-trade bills, Senate leader Kevin de León dined with Perea and Rubio at an intimate Sacramento restaurant known for $44 steaks.

De León, a Los Angeles Democrat who has carried many clean energy bills, said former lawmakers didn’t get any special treatment from him.

“I sit down with everybody across the spectrum. That’s my job as the leader of the Senate,” he said. “I have to sit down with all perspectives, whether it’s oil, whether it’s clean energy, whether it is labor unions, whether it’s businesses.”

After Perea became a lobbyist, he met with Assembly Speaker Anthony Rendon to talk about cap and trade, and held additional meetings with the speaker’s staff, Rendon acknowleged. But the speaker rejected the idea that former lawmakers were especially influential in negotiating the next phase of California’s landmark climate policy.

“On an issue like cap and trade, where members arrive with a certain set of values and with information already, I am inclined to think that this is less impactful,” Rendon said.

On the other hand, former lawmakers—especially those who served most recently—can bring unique insider know-how to any lobbying effort. They understand caucus dynamics, know how to tailor persuasive messages to particular legislators, and enjoy unusual access to public officials.

Signs of that were on display throughout the year in the bustling Capitol. In April, Parra participated in a lunchtime discussion with legislative staffers about professional advancement for women of color, joined by a legislator, a lawmaker’s chief of staff and an aide to the governor who works on environmental issues. And in September, as lawmakers began a long night voting on dozens of bills, Perea strolled down a Capitol hallway packed with lobbyists and slipped into the back door of the Assembly chamber—right past a sign labeling the room restricted to “members and staff only.”

Well-connected environmental advocates also roam the halls. Last year, for example, the Assembly honored former legislator Christine Kehoe, a San Diego Democrat who now runs a group that works to expand use of electric vehicles.

Frequently when politicians leave office, they take a job developing a lobbying strategy—but not directly lobbying. Rubio did that when he quit the Legislature in 2013 to work for Chevron, as did Perea when he resigned in 2015 to work for a pharmaceutical trade association. But as the cap-and-trade negotiations heated up this year, both officially registered as lobbyists—a sign that they anticipated having a lot more direct contact with lawmakers. Perea left the pharmaceutical group to join the Western States Petroleum Association as a registered lobbyist in May. The next month, Rubio registered as a lobbyist for Chevron. In September, he filed paperwork with the Secretary of State ending his registration as a lobbyist. (Both men scored spots this year on a popular list of the 100 most influential players around the Capitol.)

Fuentes was elected to the Los Angeles City Council after he was termed out of the Assembly in 2012. He quit the City Council last year to become a lobbyist with a firm called the Apex Group, whose many clients include Aera Energy—a firm that drills for oil in the San Joaquin Valley.

Parra, after being out of elected office for eight years, was hired by Tesoro (now Andeavor) in November as a manager of state government affairs.

No one has complained to California’s political watchdog that the former lawmakers broke any ethics rules in their advocacy work this year. The assemblyman carrying the bill to lengthen the time lawmakers are banned from lobbying said it’s not inspired by any of the Legislature’s recent departures.

Still, even if legal, the idea that personal relationships may influence statewide policy can be disconcerting, said Jessica Levinson, a professor at Loyola Law School and president of the Los Angeles Ethics Commission.

“If we think about what we’re worried about when it comes to any lobbyist, it’s the idea that our lawmakers are making decisions based on what hired guns are asking them to do as opposed to what’s good public policy,” Levinson said.

“Lobbyists have an outsized influence on lawmakers, and that is exponentially increased when that lobbyist is a former lawmaker.”

Even if former lawmakers held office at different times from today’s legislators, they may be connected through other political circles. That was the case for Assemblywoman Lorena Gonzalez Fletcher, whose time in the lower house coincided with Perea but not the other three. She knew them, though, through California’s larger network of Latino Democrats.

Gonzalez Fletcher said she never felt she was being pressured by the former legislators as the cap-and-trade negotiations advanced—perhaps because she declared her support for the bill early. Still, she saw them around the Capitol or ran into them while out for after-work drinks.

“There was a lot of checking in: ‘Where are people? Where do you think things will land?’ It felt more like information-gathering in my brief discussions with former members,” Gonzalez Fletcher said. “I didn’t feel a lot of hard lobbying going on.”

At a time when many lawmakers worry that Sacramento’s lobbying corps isn’t as diverse as the either the state or the Legislature (Latinos make up 39 percent of Californians and 23 percent of state legislators), the oil industry has been represented by black and Latino lobbyists in the Capitol for several years. Its move to bring on the four Latino former lawmakers reflects a larger economic shift in California.

“It’s not because they are Latino,” said Mike Madrid, a Republican political consultant with expertise in Latino politics. “It’s because they represented districts that are poor and working class. There just happens to be a very strong relationship between race and class in California.”

Madrid said working-class communities respond to industry arguments about the cost of environmental regulation—either as consumers who will see the cost of gas increase, or as workers who want to keep blue collar jobs in their regions. With Republicans divided over cap and trade, and lacking much clout in the Capitol, it was logical for oil to bring on some prominent Democrats.

“You’re starting to see a transformation of what has traditionally been a right-left red-blue Republican-Democrat divide,” he said. “There is a realignment occurring.”

Another indication emerged five days before lawmakers voted on the cap-and-trade extension: The California Business Roundtable, a group of 30 companies including Chevron and Valero, enlisted a new lobbyist: Richie Ross, former bare-knuckles chief of staff to one of the most powerful Democratic Assembly speakers in state history, Willie Brown.

Today, Ross is unusual among Sacramento lobbyists because he is also a political consultant whose clients include 10 Democratic legislators—giving him financial connections both to the groups that pay him to lobby and the politicians who pay him for campaign advice.

He said he provided advice to the Roundtable and did not lobby his political clients in the Legislature: “They had me register (as a lobbyist) because at that point everyone was uncertain as to whether they would need me to lobby.”

The Roundtable’s president, Rob Lapsley, is a long-time Republican. But he said business groups knew that when it came to cap and trade, they needed Democrats involved to get the plan they wanted from a Democratic-controlled Legislature.

“Richie is a smart, strategic advisor with long-term relationships. We found that of great value,” Lapsley said. “He goes back a long way. And he was very helpful in getting additional insights.”