Journalists and elected officials occasionally make the mistake of viewing budget problems in terms of size rather than where the budget item falls. For example, the costs of unfunded pensions and retiree healthcare in the current fiscal year (FYE16–17) add up to 6% of the state’s General Fund, a much smaller share than retirement spending in, say, Los Angeles where retirement spending consumes 20% of the local budget. But all the consequences of that 6% fall on a small portion of the General Fund. That’s because General Fund expenditures are like a waterfall in which money is first captured by expenditures protected by constitution, contract or statute. Unprotected programs get funded from the balance. For example:

Assume General Fund revenues this fiscal year are $100. The first $40 plus unpaid balances (if any) goes to K-14 education as a result of constitutional protection (Proposition 98). The next $7 goes to General Obligation bond debt service as a result of constitutional and contractual protection and another $7 goes to pensions and retiree healthcare as a result of contractual protection*. Medi-Cal, a statutory entitlement, takes 15% of the General Fund (plus additional amounts from Special Funds) and another 7% is consumed in part by entitlements administered by the Department of Social Services. Together, those protected obligations (ie, K-14, debt service, pensions, OPEB, Medi-Cal and DSS) will consume 78% of the General Fund this fiscal year, up from 69% just six years ago.

That leaves only 22% (ie, 100–78) for everything else, but that 22% must also cover Corrections, CHP and CalFire, all involving public safety and politically protected by powerful government employee unions. Public safety takes 10+% of the General Fund, leaving only 12% for UC, CSU and other discretionary categories not protected by contract, statute or the constitution. That’s down from 21% just six years ago; ie, the share of the General Fund available for discretionary items declined 43% in just six years.

The share of the General Fund available for UC, CSU and other discretionary categories declined 43% in just six years.

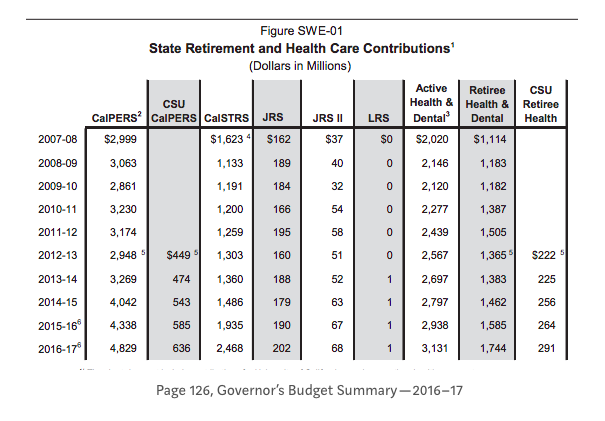

General Fund revenues were robust over that six-year period, growing 28%, and were even enhanced by a substantial tax increase, but UC and CSU saw only 19% and 23% growth in state spending. That’s in part because General Fund spending on pensions and retiree healthcare grew 99% and 47%.

Looked at another way, California’s General Fund is no different than a household in which discretionary spending is a function of how much is left over after non-discretionary spending. If your salary rises less than your mortgage and healthcare costs, you must reduce discretionary spending.

This explains how UC, CSU and other discretionary programs are paying the price for rapid growth in unfunded retirement costs. Every dollar by which protected expenditures exceed revenue growth comes out of unprotected pockets. After so many years of degradation (state spending on retirement costs has grown 70% since FYE11; see below), now only 12% of the General Fund is left to fund them — and that’s after a seven year bull market. Just imagine the consequences when revenues revert to the mean. That’s what happens when unfunded retirement obligations are not seriously addressed.

Pension and OPEB costs are just starting their sharp rise. Action can be taken. For the benefit of discretionary programs, taxpayers and fee-payers, legislators and governors should pay attention.

*There is an argument that pensions and retiree healthcare are senior to or at minimum pari-passu with debt service (see eg bankruptcy court decisions relating to Stockton and Detroit) but in the case of a state that cannot declare bankruptcy and that has the power to tax, that’s probably a distinction without a substantive difference.