From one end of California to the other, hundreds of cities are facing a tsunami of pension costs that officials say is forcing them to reduce vital services and could drive some—perhaps many—into functional insolvency or even bankruptcy.

The system that manages pension plans for the state government and thousands of local governments lost a staggering $100 billion or so in the Great Recession a decade ago and has not recovered. The California Public Employees’ Retirement System (CalPERS) is rapidly increasing mandatory contributions into its pension trust fund to make up for those losses, cope with a host of rising expenses and, it would appear, stave off the prospect of its own insolvency.

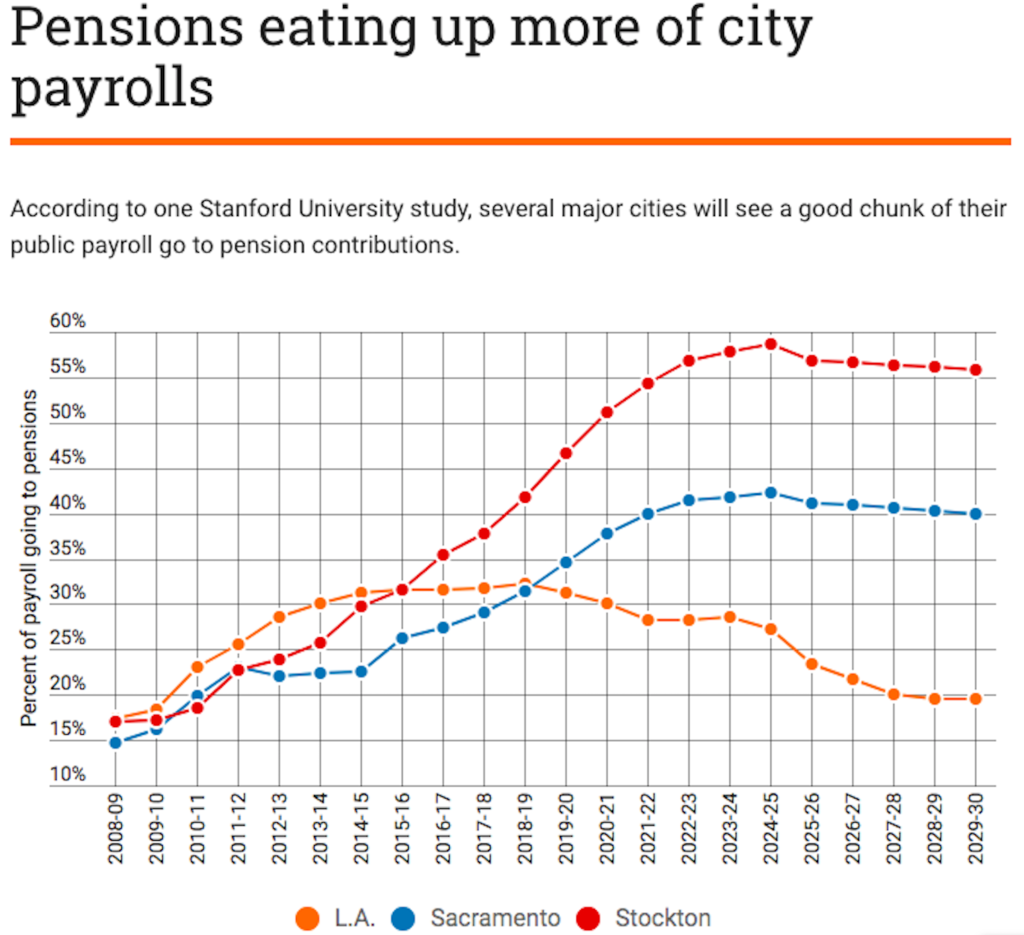

City managers, facing annual increases in contributions of 15-plus percent, are feeling the squeeze, which a new Stanford University study finds is crowding out “resources needed for public assistance, welfare, recreation and libraries, health, public works, other social services, and in some cases, public safety.”

Marina Gallegos, the human resources officer for Salinas, spoke for many city officials when she told CalPERS representatives who briefed her city council on the increases: “This growth is unsustainable.”

“Unsustainable” is a word that pops up frequently in public statements and interviews with local leaders, along with the “B-word.”

“We don’t know how we’re going to operate,” Oroville’s finance director, Ruth Wright, told the CalPERS board last year as a delegation of city officials pleaded for relief. “We’ve been saying the bankruptcy word.”

While all CalPERS client agencies, including school districts, counties and the state itself, are being hit by its rising demands for money, the state’s 482 cities are being clobbered the hardest. They devote the vast majority of their budgets to personnel costs, particularly for firefighters and police officers who have the most generous pension benefit—up to 90 percent of their highest earnings—and thus incur the highest pension costs.

It’s common for California cities to pay 50 cents into the pension fund for every dollar in salary for their police officers, and only slightly less for firefighters. Studies indicate that costs of police pensions could increase by 50 percent within a few years and even double as CalPERS continues to deal with a large “unfunded liability”—essentially a debt—for pension promises.

Lodi’s city manager, Steve Schwabauer, told CalPERS’ trustees, “I have the unfortunate obligation to tell you that Lodi is on a slow, inexorable slide toward insolvency if you maintain your present course.” He and other city officials pleaded for relief but so far have not received it.

Three California cities have declared bankruptcy in recent years, and fast-rising pension costs have been major factors in all. One was Vallejo, whose recently retired city manager, Daniel Keen, joined his colleagues in seeking relief, saying he expected pension costs for police to reach 98 percent of payroll in a decade and hinting that Vallejo could slip into insolvency again.

A new study for the League of California Cities, conducted by a consulting firm, Bartel Associates, projects that over the next seven years overall city pension costs, excluding health care, will nearly double, reaching an average of 15.8 percent of their general fund budgets by 2024-25. Costs for police and fire personnel will climb to well over 60 percent of payroll.

“The results of this study provide additional evidence that pension costs for cities are approaching unsustainable levels,” Bartel’s report warns. As those burdens outstrip revenue growth, it says, “many cities face difficult choices that will be compounded in the next recession.”

But CalPERS’ officials, trying to steady the fund’s own precarious financial position, are openly worried that if they don’t increase the bite on public employers or see investment earnings rebound sharply, they will drift to a still-undefined point of no return, unable to meet obligations under any circumstances.

CalPERS is also facing a wave of retirements from baby-boom-generation workers, the need to adjust for retirees’ longer lifespans and a tab for benefits that were increased sharply in the late 1990s and early 2000s.

It’s a perfect financial storm.

In 1999, the Legislature and a newly inaugurated Democratic governor, Gray Davis, retroactively expanded benefits by roughly 50 percent for state employees. Most cities, counties and other local governments, under pressure from their unions to match the state, quickly followed suit. They all relied on CalPERS’ assurances that its trust fund could absorb the costs without additional contributions.

As a state Senate analysis of its pension bill, SB 400, summarized: CalPERS “believes they will be able to mitigate this cost increase through continued excess returns.”

That assertion crumbled a few years later, when “excess earnings” became immense losses. CalPERS has just 68 percent of the money it projects it needs to cover pension promises to millions of current and future retirees—down from 101 percent a decade earlier. Also, the funding level assumes that investment earnings will hit 7.5 percent per year now and slide slowly to 7 percent.

Critics, such as those behind the Stanford study, say that assumption, called the “discount rate,” is unrealistically high. CalPERS’ own staff says it cannot count on more than 6.1 percent in the next decade, partly because CalPERS is shifting to a more conservative investment strategy.

Despite that seeming anomaly, CalPERS officials say the 7 percent assumption is likely to be reached in the decades-long time frame in which they operate, as modest earnings in the near future are offset by higher earnings later. Its board decided in December not to lower the rate further, which would have required even higher contributions from client agencies.

Larger cities that operate their own pension systems are not immune to the syndrome, since they have also experienced weak investment earnings.

Officials in Los Angeles have calculated that its pension costs have more than doubled, from $435 million a year in 2005-06 to $1.1 billion currently, and are expected to hit $1.3 billion by the end of the decade.

San Diego’s annual pension costs have leaped from $191 million to $228 million in the last two years. City finance director Tracy McCraner says, “We’ve been told that could possibly rise to the tune of about $10 million” next year.

Cities want CalPERS to explore other responses to a more conservative earnings assumption, beyond merely increasing employer payments. They want CalPERS to rein in its costs, by such means as modifying or even suspending cost-of-living increases for current retirees with especially high pensions.

Watch one city’s payroll get swallowed by pensions

Source: Joe Nation, “Pension Math: Public Pension Spending and Service Crowded Out in California, 2003-2030.” Stanford Institute for Economic Policy Research, 2017.

However, the board’s response has been negative, reflecting its domination by public employee unions and union-allied politicians who stoutly resist any downward pressure on pension benefits.

Seeing no broad relief from CalPERS itself, city officials are beginning to lobby Gov. Jerry Brown and legislators for help. But they are not sanguine about their chances, given the heavy influence that the unions also have in the Capitol. Rather, Brown is openly hoping that the state Supreme Court will intervene via pending cases that would eliminate or modify the so-called “California rule”—an assumption, based on a 1955 state Supreme Court ruling, that pension benefits, once granted, can never be changed.

A key phrase in one of the recent appellate court rulings, reinterpreting the 1955 decision and now before the Supreme Court, frames the issue.

“While a public employee does have a ‘vested right’ to a pension,” appellate Justice James Richman wrote, “that right is only to a ‘reasonable’ pension— not an immutable entitlement to the most optimal formula of calculating the pension.”

In November, Brown filed a lengthy brief backing the appellate court rulings, thus putting himself at odds with the unions and defending reforms he had championed.

The cases arose because unions challenged a relatively mild pension-reform measure that Brown and legislators enacted five years ago. It is aimed at reducing benefits for new employees, eliminating the “spiking” of pensions by including abnormal salary income in pension calculations, canceling employees’ ability to buy more pension credits, called “airtime,” and forcing employees to pay greater shares of pension tabs.

However, its effects are not expected to have a major impact on payments to CalPERS, or the independent pension funds maintained by some large local governments, for a number of years. And if the reform does level off current costs for current employees—probably after 2030—overall high costs will likely continue to support a much larger cadre of baby-boomer retirees drawing old-style, pre-reform pensions with high benefits.

If, as city officials fear, they get no relief from CalPERS or in the Capitol, and their pension costs continue to escalate to unsustainable levels, they have several options, some of which are already being pursued:

- Negotiate lower levels of benefits with unions for pre-reform employees, to supplement the lower levels for new workers—an option that the pending state Supreme Court case could make more viable;

- Negotiate contracts that shift a greater share of pension costs to employees, particularly in cities that have been picking up employee shares;

- Reduce future obligations by making lump-sum payments, emulating a $6 billion extra payment that Brown included in his 2017-18 budget toward future state liabilities. Brown is borrowing the money from a state fund that invests extra cash, and some cities have floated “pension obligation bonds” to do the same;

- Cut city services to fund special reserves for future pension cost increases;

- Raise taxes;

- Declare bankruptcy.

As they await the Supreme Court’s ruling and weigh their options for dealing with ever-increasing demands from CalPERS, city officials find that each one comes with its own set of difficulties. One city manager confided, for instance, that when he proposed to leave some parks positions vacant and shift the salary savings into a pension reserve, he told his council that it also would mean reducing park services, such as restroom maintenance. Fearing backlash from constituents, the council ordered that the jobs be filled.

When Stockton went through bankruptcy, the federal judge handling the case, Christopher Klein, issued a lengthy opinion that despite the “California rule,” federal law could allow bankrupt cities to reduce benefits. “I’ve had more than 138,000 bankruptcy cases,” Klein wrote. “I’ve been party to impairment of millions of contracts and it’s all constitutional.”

Stockton, Vallejo and San Bernardino, under pressure from CalPERS and their unions, did not try to reduce benefits while in bankruptcy. But Klein’s opinion sits in the background, waiting for some insolvent public agency to test its validity.

The option that many cities have already taken, and dozens of others are considering, is to raise local taxes, especially sales taxes—although only rarely do they tell voters that the new revenue is needed for pensions.

More generally, they portray the tax boosts as ways to improve police and fire services and keep specific promises to voters, such as adding police patrols or opening fire stations. They know that eventually, as pension costs rise, they will have to rescind those steps.

Privately, some city officials are encouraging their unions to put pension-related tax increases on the ballot via initiative, because a recent court decision indicates that an initiative tax would have a lower vote requirement than one proposed by a city council. Thus it would be easier to enact.

That said, tax increases alone cannot deal with pension costs that are rising so quickly. State-local sales tax rates are now at or above 10 percent in many communities, and taxable retail sales have flattened out as a percentage of personal income.

A final note: All of this is occurring during a period of general economic prosperity.

Were recession to hit, local revenue, particularly from sales taxes, would be adversely affected. And as the last big recession demonstrated, CalPERS and other pension funds would likely take another big hit.

That could be a recipe for municipal fiscal disaster on a broad scale.