If the June 5 primary is the prelude to the November general election, the California Democratic Party is set to hold a prelude to the prelude.

This weekend members of the state’s dominant party will meet in San Diego for its annual convention. Platform writing and morale boosting aside, the main task will be to pick which candidates get to run with the state party endorsement.

The results might actually matter this time. Four Democratic gubernatorial candidates will be trying to win the party’s backing—or keep it away from their opponents. U.S. Sen. Dianne Feinstein faces an increasingly credible challenger in state Sen. Kevin De León. And hopes of a blue wave this November have yielded a bumper crop of progressive candidates vying for congressional and legislative seats.

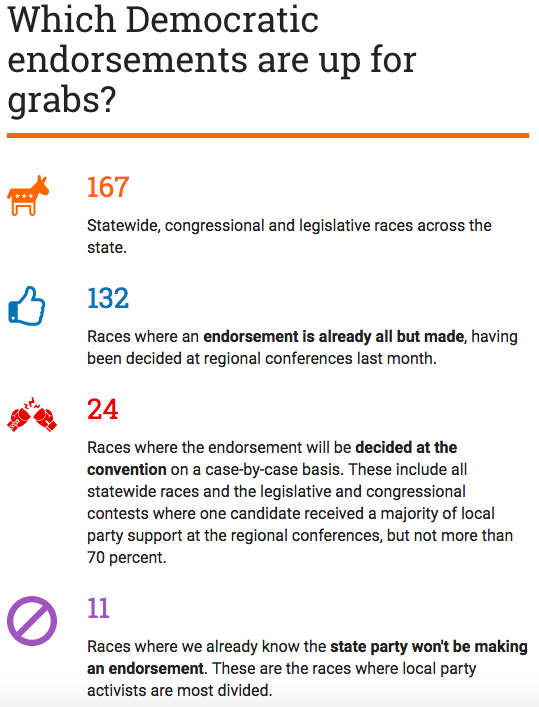

At stake: 167 race endorsements, although most have already been approved at the local level. For the statewide races and some unresolved local ones, however, things are expected to get rowdy.

Start at the top of the ticket: None of the gubernatorial campaigns are projecting an easy endorsement win, which for statewide races requires 60 percent of the delegate vote. Even the candidate who’s been seen as the front-runner is hinting of a stalemate.

“It will be extremely difficult for any gubernatorial candidate to get to 60 with such a big field,” said Nathan Click, a spokesperson for Lt. Gov. Gavin Newsom’s campaign.

Meanwhile, the Antonio Villaraigosa campaign is already discounting the gravity of a possible defeat. “Gavin Newsom has been working for this endorsement virtually non-stop for nine years. He’s counting on a victory, ” Villaraigosa campaign spokesman Luis Vizcaino said. “But the only predictable thing about a Democratic Party convention is that it is unpredictable.”

Why all the fuss?

On paper, running as the party’s chosen candidate doesn’t count for much. Anyone can campaign as Democratic, and the endorsement won’t even appear on the ballot itself—although avid readers of the sample ballot will find the information there.

An endorsement doesn’t necessarily mean more cash either. The party may direct some extra money to favored candidates in competitive races, but party leaders say they don’t want to be seen picking winners. Not after 2016. In Dem-on-Dem contests in progressive districts, the party doesn’t plan to spend “anything beyond the minimum of including (endorsed candidates) in slate cards,” said party spokesperson John Vigna.

Still, the state party mantle seems worth fighting for.

The California Republican Party has traditionally been reluctant to put its thumb on the scale by endorsing before the primaries, but changed its mind after no Republican made it onto the general ballot in the 2016 U.S. Senate race. The party will hold its endorsement convention in early May.

According to one study, candidates with the party’s backing perform 6 to 15 percentage points better in a subsequent primary than similarly qualified, but non-endorsed opponents—a sizeable, if not insurmountable advantage.

In down-ballot races, the party endorsement can help a little-known Democrat stand out from the progressive pack. It can also boost a candidate’s credibility with funders and other endorsers. And in races where there is already a presumed front-runner, the outcome of an endorsement battle can either reaffirm the obvious, or prompt voters to reconsider the conventional wisdom.

“Gavin having more money than John (Chiang), Delaine (Eastin), Antonio (Villaraigosa), doesn’t mean anything if he can’t win the support of the party,” said Drexel Heard, a delegate from the San Fernando Valley who supports Newsom.

For progressive voters wary of party meddling—say, Bernie Sanders supporters from 2016, or those who backed Kimberly Ellis for party chair at last year’s convention—the party imprimatur could indicate which candidate not to vote for.

Still, “party endorsements do separate candidates, and unless you’re running against ‘the Establishment,’ it’s probably better to have it than not,” said Larry Gerston, a political science professor emeritus at San Jose State University.

For some campaigns, this endorsement fight will be one of the last opportunities to prove their viability before the primary.

Take the case of de León, who just received the backing of two powerful labor groups, the Service Employees International Union and the California Nurses Association. A surprise win—or even a strong showing—against incumbent Feinstein would signal to voters that the U.S. Senate contest isn’t the foregone conclusion that public opinion polls have so far made it out to be.

Likewise in the attorney general’s race, it’s a chance for Insurance Commissioner Dave Jones to remind party members that before Gov. Jerry Brown appointed Xavier Becerra to the job, he was the presumed front-runner for a reason.

In other races, the contest is less a question of “who” than “if.”

Newsom remains the slight favorite in the gubernatorial endorsement contest, but his three opponents have their own reserves of support. Their best strategy might be to ensure that no one clears the 60 percent threshold.

The endorsement process for congressional and legislative races, which began last month at regional party meet-ups across the state, is more complex.

If those candidates received 70 percent or more of the vote of delegates and party activists at regional conferences, the endorsement is all but made. In districts where the delegate vote was more divided, an endorsement will either be debated at the convention, or it won’t be awarded at all.

That creates a conundrum for the Democratic Party heading into the midterms, said University of California, San Diego political scientist Thad Kousser, who co-authored the endorsement study.

“Party endorsements could matter the most in the congressional seats where parties are least likely to make them,” he said.

Consider the 10 California districts recently identified as possible pick up opportunities by the Democratic Congressional Campaign Committee. These red-going-on-purple congressional seats are central to Democratic aspirations of taking back the House this November.

But so far, the state party has only offered endorsements in just two of the 10: to Emilio Huerta in the southwest San Joaquin Valley, and to Ammar Campa-Najjar in east San Diego County. Of the remaining eight, six will be contested at the convention. Two won’t get an endorsement, period.

That’s of particular concern for the party given California’s primary process. Under the “top two” system, only the first and second most popular candidates in June move on to the general election, regardless of party. In the seats occupied by Republicans Darrell Issa of Vista and Ed Royce of Fullerton, both of whom aren’t seeking reelection, too many Democrats with limited name recognition could split the left-of-center vote, allowing two Republicans to grab the top two spots.

“Winnowing the Democratic field could be vital to ensuring a Democrat in the top two,” said Kousser. But “it will be tough for a divided party to endorse.”

It’s already too late for Royce’s district, where the field is thoroughly divided across seven Democrats. This weekend, Mike Levin will fight for his endorsement in Issa’s district against likely opposition from four of his fellow party members.

Call it the enthusiasm paradox.

“You have an influx of people running, which is a good thing,” said Merced delegate Alejandro Carrillo. “But it definitely adds to the divide.”

Delegates also will have to reconsider their endorsement Assemblywoman Cristina Garcia of Los Angeles, who stands accused of sexual misconduct. The party may have just dodged that awkward debate in the case of state Sen. Tony Mendoza, another Los Angeles legislator facing sexual harassment allegations, who resigned on the eve of the convention.

At the same time, local intraparty spats will be dredged up for the whole party to consider.

Last week, Harley Rouda, running for Congress in Orange County, launched an ad attacking fellow Democrat Hans Keirstead. With Keirstead seeking a convention endorsement, Rouda’s team has been in full campaign mode this week—making calls, organizing coffee dates, and sending rafts of postcards to convince delegates not to endorse the other Democrat.

It’s all good practice for the elections to come.