The California Supreme Court pushed the three states initiative off the November ballot probably on its way to being shoved out the door permanently once the court examines the proposal more closely. With attention focused on the three states initiative recently, we have heard about the approximate 200 efforts over the years to cut California into smaller pieces. But there is a lesser-known history dealing with the size of California. At the beginning of the state’s founding, during the constitutional convention of 1849, there was an effort to make California much larger than it is today.

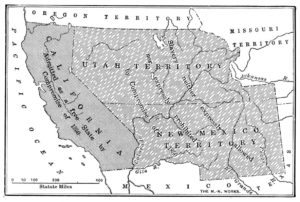

One of the more lively debates at California’s first constitutional convention in Monterey centered on California’s boundaries. A proposal substituted for a plan put forth by the boundary committee would extend California eastward to include the New Mexico territory and the Great Salt Lake and lands east to the Rocky Mountains. For a time, it gained majority support at the convention and won a vote to substitute for the original boundary plan.

William Gwin, who would become one of California’s initial United States Senators, put forth the plan. He was a man of southern sympathies and pro-slavery, facts that, in part, inspired his plan. But that’s not what he told the convention.

Gwin’s idea was to bring California in as a huge state and eventually carve it up into many states so as to gain power in the senate by adding more senators. Gwin told the convention, “If you are seeking power for your state your object should be to make it as small as possible.” And, “I wish we could get it divided into two or three states.”

In an echo to Tim Draper’s more modern plan, Gwin said eventually he wanted six states and he declared he had no doubt there would be 20 states west of the Rockies. “When the population comes, they will require that this state shall be divided.”

But there was pushback to Gwin’s plan soon after it won its initial vote. There was concern about including the Salt Lake area with its Mormon residents in the state of California. The Mormons were considered a sect peculiar to Californians. One delegate arguing, the Utah Territory area was “settled now by a large population of people, whose religious tenets certainly form a great barrier to their introduction among the people of California.”

There were also objections to including the Utah Territory in the new state of California when the wishes of the people of that area were not represented at the convention.

Further, there was the issue of someone chosen as a representative from so far away needing to travel months to get to the legislature. One delegate expressed horror that such an arrangement might require that California institute a full time legislature.

Imagine that. A full time legislature!

But boiling below the surface and eventually becoming part of the debate was the slavery question. Opponents of the plan argued it was just a method to bring slaves into California. Miners were against importing slaves and competing with slave labor in the diggings. Gwin was charged with setting up a plan to eventually create a number of states so that some would accept slavery. In the end, California prohibited slavery.

Finally arguments were made that creating such a large state would injure California’s chances of gaining statehood. Congress would object, it was argued. A new proposal establishing the Sierra Nevada as California’s eastern border carried the day.

A record of California’s 1849 constitutional convention were recorded and published by J. Ross Browne. The debate on the state boundaries begins on page 167.

The saga of attempting to re-shape California began at its birth and continues today with Draper’s latest effort. It appears from the Supreme Court’s action that if California is to take a different form, Draper or someone else is going to have to try again.