California’s new governor, Gavin Newsom, delivered an inaugural addressearlier this week that accurately reflected the mentality of his supporters. Triumphalist, defiant, and filled with grand plans. But are these plans grand, or grandiose? Will Governor Newsom try to deliver everything he promised during his campaign, and if so, can California’s state government really deliver to 40 million residents universal preschool, free community college, and single payer health care for everyone? It’s reasonable to assume that to execute all of these projects would cost hundreds – plural – of billions per year. Where will this money come from?

While California’s budget outlook currently offers a surplus in excess of $10 billion, that is an order of magnitude less than what it will cost to do what Newsom is planning. And this surplus, while genuine, is the result of an extraordinary, unsustainable surge in income tax payments by wealthy people. California’s tax revenues are highly dependent on collections from the top one-percent of earners, and over the past few years, the top one-percent has been doing very, very well. Can this go on?

To illustrate just how unusually swollen California’s current state tax revenues have gotten, compare state tax collections in FYE 6/30/2017 (our most recent available data) to seven years earlier, in 2010.

Back in 2010, California was in the grip of the great recession. Total state tax revenue was $94 billion, and $44 billion of that was from personal income taxes. Skip to FYE 6/30/2017, and total state tax revenue was $148 billion, and $86 billion was from personal income taxes. This means that 80 percent of the increase in state tax revenue over the seven years through 6/30/2017 was represented by the increase is collections from individual taxpayers, which doubled.

It isn’t hard to figure out why this happened. Between 2010 and 2017 the tech heavy NASDAQ tripled in value, from 2,092 to 6,153. In that same period, Silicon Valley’s big three tech stocks all quadrupled. Adjusting for splits, Apple shares went from $35 to $144, Facebook opened in May 2012 at $38, and went up to $150, Google moved from $216 to $908.

While California’s tech industry was booming over the past decade, California real estate boomed in parallel. In June 2010 the median home price in California was $335,000; by June 2017 it had jumped to $502,000. Along the California coast, median home prices have gone much higher. Santa Clara County now has a median home price of $1.3 million, double what it was less than a decade ago.

As people sell their overpriced homes to move inland or out-of-state, and as tech workers cash out their burgeoning stock options, hundreds of billions of capital gains generate tens of billions in state tax revenue. But can homes continue to double in value every six or seven years? Can tech stocks continue to quadruple in value every six or seven years? Apparently Gavin Newsom thinks they can. Reality may beg to differ.

Just a Slowdown in Capital Gains Will Cause Tax Revenue to Crash

The problem with Gavin Newsom’s grand plans is that it won’t take a downturn in asset values to sink them. All that has to happen to throw California’s state budget into the red is for these asset values to stop going up. Just a plateauing of their value – which, by the way, we’ve been witnessing over the past six months – will wreak havoc on state and local government budgets in California.

The reasons for this are clear enough. Wealthy people, making a lot of money, pay the lion’s share of state income taxes, and state income taxes constitute the lion’s share of state revenues.

Returning to the 2017 fiscal year, of the $86 billion collected in state income taxes, $28 billion was from only 70,437 filers, all of them making over $1.0 million in that year. Another $7.3 billion came from 131,120 filers who made between a half-million and one million in that year. And since making over $200,000 in income in one year is still considered doing very, very well, it’s noteworthy that another 807,000 of those filers ponied up another $15.1 billion in FYE 6/30/2017.

There is an obvious conclusion here: if people are no longer making killings in capital gains on their sales of stock and real estate, California’s tax revenues will instantly decline by $20 billion, if not much more. And it won’t even take a slump in asset prices to cause this, just a leveling off.

Debt, Unfunded Pension Liabilities, Neglected Infrastructure

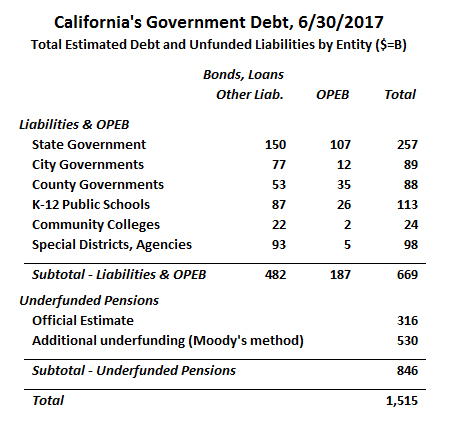

When considering how weakening tax revenues in California will impact the ability of the state and local governments to cope with existing debt, it’s hard to know where to begin. To get an idea of the scope of this problem, the California Policy Center just released an analysis of California’s total state and local government debt.

As shown on the table, California’s total state and local government debt as of 6/30/2017 is over $1.5 trillion. More than half of it, $846 billion, is in the form of unfunded pension liabilities.

Calculating pension liabilities is a complex process, with controversy surrounding what assumptions are valid. In basic terms, a pension liability is the amount of money that must be on hand today, in order for withdrawals on that amount – plus investment earnings on that amount as it declines – to eventually pay all future pensions earned to-date for all active and retired participants in the fund. Put another way, a pension liability is the present value of all pension benefits – earned so far – that must be paid out in the future. The amount by which the total pension liability exceeds the actual amount of assets invested in a fund is referred to as the unfunded liability.

The controversy over what is an accurate estimate of a pension liability arises due to the extreme sensitivity that number has to how much the fund managers think they can earn. Using the official projection which is typically around 7.0 percent per year, the official pension liability for all of California’s government pension funds is “only” $316 billion. But Moody’s, the credit rating agency, discounts pension liabilities with the Citigroup Pension Liability Index (CPLI), which is based on high grade corporate bond yields. In June 2017, it was 3.87 percent, and using that rate, CPC analysts estimated the unfunded liability for California’s state and local employee pension systems at $846 billion. Using the methodology offered by the prestigious Stanford Institute for Economic Policy Research, California’s unfunded pension debt is even higher, at $1.26 trillion.

Where pension liabilities move from controversial theories to decidedly non-academic real world consequences, however, is in the budget busting realm of how much California’s government agencies have to pay these funds each year. California’s public sector employers contributed an estimated $31 billion to the pension systems in 2018. Extrapolating from officially announced pension rate hikes from CalPERS, California’s largest pension system, by 2024 those payments are projected to increase to $59 billion. And these aggressive increases the pension systems are requiring are a reflection more of their crackdown on the terms of the “catch up” payments employers must make to reduce the unfunded liability than on a reduction to their expected real rate of return.

Huge unfunded pension liabilities are another reason, equally significant, as to why California’s state budget is extraordinarily vulnerable to economic downturns. If assets stop appreciating, not only will income tax revenue plummet. At the same time, expenses will go up, because pension funds will demand far higher annual contributions to make up the shortfall in investment earnings.

A cautionary overview of the economic challenges facing California’s state government would not be complete without mentioning the neglected infrastructure in the state. For decades, this vast state, with nearly 40 million residents, has been falling behind in infrastructure maintenance. The American Society of Civil Engineers assigns poor grades to California’s infrastructure. They rate over 1,300 bridges in California as “structurally deficient,” and 678 of California’s dams are “high hazard.” They estimate $44 billion needs to be spent to bring drinking water infrastructure up to modern standards, and $26 billion on wastewater infrastructure. They estimate over 50 percent of California’s roads are in “poor condition.” In every category – aviation, bridges, dams, drinking water, wastewater, hazardous waste, the energy grid, inland waterways, levees, ports, public parks, roads, rail, transit, and schools, California is behind. The fix? Literally hundreds of additional billions.

What Governor Newsom might consider is refocusing California’s state budget priorities on areas where the state already faces daunting financial challenges, rather than acquiescing to the utopian fever dreams of his constituency and his colleagues.