The annual payment to CalPERS for state worker pensions next fiscal year is expected to be $7 billion, a jump from $6.4 billion this year — and a quantum leap from $160 million when a pension increase, SB 400, was approved 20 years ago.

It was 1999 and CalPERS was in its golden years, thanks to a booming stock market. Investment earnings had averaged 13.5 percent for a decade, soaring in the two prior years to 20 percent. Funding for a half dozen state and school plans ranged from 100 to 139 percent.

Faced with a “surplus,” CalPERS was about to do what California public pension systems have done (see CalSTRS and UC) since voters approved measures allowing a shift in investments from predictable bonds to higher-yielding but riskier and unpredictable stocks.

Instead of preparing for a market downturn and leaner times, the “surplus” funds were spent on cutting employer payments into the pension system and raising employee pensions, some retroactively.

The CalPERS-sponsored legislation that raised pensions, SB 400, became infamous for driving up state employer costs and setting a generous Highway Patrol pension formula, widely adopted by local police and firefighters, that critics say is “unsustainable.”

As if critics needed more, CalPERS gave the Legislature a 17-page pamphlet on SB 400 that quoted the CalPERS president then, William Crist, as saying SB 400 would not cost “a dime of additional taxpayer money.”

CalPERS told the Legislature the increase in pension costs would be offset by inflating the market value of investments from 90 to 95 percent, spreading surplus funds over 20 years to reduce employer rates, and continued strong investment returns.

“They (CalPERS) anticipate that the state’s contribution to CalPERS will remain below the 1998-99 fiscal year ($766 million) for at least the next decade,” said the Assembly floor analysis of SB 400.

What the Legislature was not shown was a CalPERS actuarial forecast of what would happen if investment returns during the next decade averaged 4.4 percent, instead of the expected 8.25 percent.

In that scenario, CalPERS actuaries forecast that the state contribution a decade later would be $3.9 billion, not below $766 million as the Legislature was told. As it turned out, the state contribution in 2009 was $3.9 billion, though 10-year earnings averaged only 3.1 percent.

Whether knowing the downside would have made a difference as SB 400 sailed through the Legislature (Senate 39-to-0, Assembly 70-to-7) is debatable. Unions had strong support in the Legislature, even from conservative Republicans allied with prison guards.

Former Gov. Gray Davis’ personnel director, Marty Morgenstern, used the 4.4 percent earnings scenario to bargain a small reduction in the SB 400 pension formula for miscellanous state and non-teaching school employees.

“If future returns are more like those earned between 1966 and 1975, the State could end up contributing over $3.9 billion a year to maintain the new benefit level, according to CalPERS actuaries,” said a Morgenstern bargaining update on July 22, 1999.

“Thus the administration believes that the State’s ability to afford employee benefits in any reasonable foreseeable circumstances could be in jeopardy if we are not careful in implementing pension improvements.”

CalPERS has not viewed SB 400 as a main driver of increased state pension costs. In a CalPERS breakdown of the state contribution changes between 1997 and 2014, SB 400 accounts for 18 percent of the increase. Other benefit changes caused 5 percent of the change.

Most of the rate change, 46 percent, was due to investment gains and losses and changes in demographic assumptions, actuarial methods and contributions. An increasing state payroll accounts for 31 percent of the rate change during the period.

One of the arguments for SB 400 in the CalPERS pamphlet, titled “Addressing Benefit Equity,” was that most local government employees in CalPERS received a higher pension than state workers.

Legislation in 1990 allowed non-safety local government employees to receive a “2 at 55” pension formula, providing 2 percent of final pay for each year served at age 55. An employee could start work at age 30 and retire with 50 percent of pay at age 55.

Most “miscellaneous” non-safety state workers were still receiving a less generous “2 at 60” formula. Adding to the inequity, miscellaneous state workers hired after July 1, 1991, had an even less generous formula, “1 at 60.”

CalPERS proposed that miscellaneous and industrial state workers and school employees receive a “2.7 at 65” formula. After bargaining, SB 400 gave these groups a lower “2 at 55” formula that increased to 2.5 percent at age 63 and above.

Employees could upgrade past service to the new formula by making contributions with interest. CalPERS retirees, getting a retroactive boost at no cost to them, received pension increases of 1 to 6 percent, depending on the amount of time they had been retired.

A well-known part of SB 400 gave the Highway Patrol a “3 at 50” formula, up from “2 at 50,” an increase of roughly 50 percent. The pension is capped at 90 percent of final pay, unlike other CalPERS formulas that allow retirement at 50 and pensions that exceed final pay.

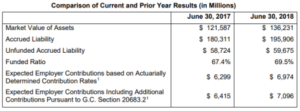

The state share of the “surplus” was, briefly, a lower annual payment to CalPERS. Contributions for state employees that had already dropped from $1.2 billion in fiscal 1997 to $776 million in 1998 were cut to $160 million in 1999 and 2000 before beginning to soar.

Some think the major impact of SB 400 came from a last-minute provision that authorized local police to receive the “3 at 50” formula bargained by the Highway Patrol, which critics have called “unsustainable.”

The extra cost for the Highway Patrol is a small part of the state budget. But for local governments police and firefighters, along with other personnel costs, are usually a big part of the budget.

How important equity is to local governments was shown in the Stockton and San Bernardino bankruptcies. Officials in both cities said they did not try to cut CalPERS pensions, their biggest debt, because of the need to be competitive in the job market.

CalPERS encouraged what some call the “ratcheting up” of pensions by offering to inflate investment values to help cover the cost of higher local government pensions authorized by AB 616 in 2001, three progressively higher non-safety formulas more generous than “2 at 55.”

The most generous, “3 at 60,” provides a pension at age 60 that is 90 percent of final pay after 30 years of service and 120 percent of pay after 40 years of service, according to a CalPERS local government benefit chart.

Former Gov. Brown’s pension reform ended “ratcheting up” for new employees hired after Jan. 1, 2013, by imposing standard formulas in CalPERS, CalSTRS and the county systems. New hires must work longer to earn pensions similar to previous formulas.

This week, the CalPERS board is expected to approve the new $7 billion state payment for the new fiscal year beginning July 1.

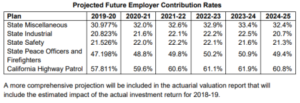

If investment earnings hit the 7 percent annual target, CalPERS projects state payments, as expressed in percentage of pay, will level off during the next five years.

Reporter Ed Mendel covered the Capitol in Sacramento for nearly three decades, most recently for the San Diego Union-Tribune. More stories are at Calpensions.com.