Investments earning 6.7 percent during the fiscal year that ended June 30 might seem like a good return, particularly after an alarming stock market drop at the end of last year.

But for CalPERS it’s a loss that creates new pension debt.

The big pension system currently needs earnings of at least 7 percent to balance its books for the year. So the small loss, .3 percent, creates a new layer of debt to add to the many layers of debt from previous years with investment losses.

The difference this year, however, is that under a reform adopted by the CalPERS board last year new debt from investment losses will be paid off over 20 years instead of 30 years, saving money in the long run.

The .3 percent loss will mean different dollar amounts of new debt when applied to the roughly 3,000 CalPERS pension plans, which vary in size and funding status. The plans cover state workers, most cities and counties, special districts, and non-teaching school employees.

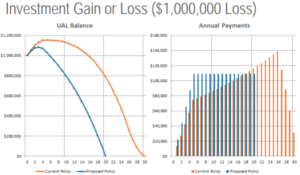

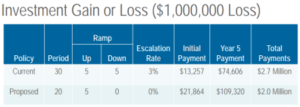

As the CalPERS charts below show, under the previous policy the cost of paying off an investment loss of $1 million would be $2.7 million over 30 years. Under the new policy, the cost drops to $2 million over 20 years.

The new policy is the second CalPERS reform since 2013, when the 30-year policy replaced an “open” or “rolling” policy to pay off or “amortize” debt from investment losses. The debt could be refinanced each year and theoretically might never be paid off.

“We moved a notch from basically ‘unacceptable’ to ‘not recommended,” Scott Terando, CalPERS chief actuary, told the board in November 2017, referring to how the switch from open to 30-year amortization is viewed under professional group guidelines.

Most California public pension systems use 15 to 20-year payment periods. Among 17 systems listed in a CalPERS staff report two years ago only the Los Angeles County Retirement Association had a 30-year payment period.

CalPERS board approval of 20-year debt payment was difficult because short-term employer costs would increase. Cities said rates, already at all-time highs and projected to increase, were forcing layoffs, program cuts and threatening the solvency of some cities.

Employer rate increases also can face resistance from powerful public employee unions, often a force on the 13-member CalPERS board. Some union officials argue that taking money off the bargaining table should be negotiated.

Failure to promptly pay down debt is one reason CalPERS funding has not recovered from heavy investment losses during a stock market crash and financial crisis a decade ago, despite a bull market of record length.

Pension funds that quickly recovered, such as the Wisconsin and Dutch systems regarded by some as models, not only promptly pay off debt from investment losses but also can cut pension payments to retirees if needed.

The CalPERS investment fund plunged from about $260 billion in 2007 to $160 billion in 2009. The funding level fell from 100 percent of the projected assets needed to pay future pensions to 61 percent.

Now CalPERS is still only 70 percent funded, even with investments valued at $375 billion last week. Though CalPERS rebounded from losses to full funding in the past, conditions have changed. The loss was unusually large and CalPERS is a maturing system.

Retirees will soon outnumber active workers. Investment funds have grown much larger than the payroll on which employer rates are based. So replacing a loss requires an employer rate increase that takes a much bigger bite out of employer budgets.

The failure to get back to 100 percent funding, or even the traditional minimum of at least 80 percent funding, leaves CalPERS little cushion to absorb a deep economic downturn or major stock market drop.

At only 70 percent, CalPERS funding is more likely to drop below 50 percent, a red line experts say could be a crippling blow making a return to full funding difficult if not impossible.

The CalPERS debt or unfunded liabiity, $139 billion, is a slippery number. It would soar if the current earnings forecast used to discount future pension debt, 7 percent, was lowered to what critics say is a more likely return.

Pension debt also varies with how it’s paid off. Under the previous 30-year CalPERS policy, debt continued to grow (“negative amortization”) until about year 17. Then growing payments began to cover the interest and reduce the principle or original amount of the debt.

An important part of the new 20-year CalPERS policy is a payment switch from “level percentage of pay,” which grows with the increase in salaries, to a “level dollar amount” that covers the interest and immediately starts reducing debt.

At the request of cities the CalPERS board changed the proposed 20-year policy to phase in the level dollar amount over five years, easing the strain of rising rates on local government budgets but also allowing debt to continue growing for five years. (see chart)

As with previous policies, CalPERS treats investment losses differently than debt resulting from “assumption” changes such as a lower discount rate, longer expected life spans, and increases in pension benefits.

The new 20-year policy for assumption changes doesn’t have a payment phase in allowing debt to grow for five years. In the example of paying off a $1 million debt, not having a phase in drops the total cost from $2 million to $1.8 million.

Many of the 3,000 CalPERS plans have a dozen or more layers of debt, each with its own amortization period. In a single year one or more layers may be added, while one or more layers may be paid off.

CalPERS encourages early payments by showing savings from shortening amortization periods to 20 years formerly and now to 15 years and 10 years. Employers have the option of collapsing several debt layers into one new layer for a “fresh start” on amortization.

If employers are struggling to make their CalPERS payments, the new policy has a “hardship” provision that, when criteria is met, allows debt payments to be extended, cutting costs in the short term but increasing them in the long run.

In years when investment earnings exceed the 7 percent target, the gain is used to reduce debt. Because losses can be reduced by future gains, CalPERS has treated losses differently than assumption changes.

“Ideally, the positives and the negatives offset one another,” Terando, the chief actuary, said last week. “So you have a loss one year followed by a gain the next year. As you amortize those, they are offsetting payments.”

Under a new “risk mitigation” policy that begins this fiscal year, when investment earnings exceed 9 percent the discount rate will be lowered slightly, dropping more as the amount over 9 percent increases.

The goal is to slowly allow a shift to lower-yielding investments with less risk of a big loss like the one a decade ago. Employer contributions would not be raised until two years after the gain over 9 percent.

A similar two-year lag, needed by actuaries to check the data for the 3,000 plans and give employers some advance notice, means the .3 percent loss last fiscal year will not begin raising employer contributions until fiscal 2021-22.

Since the funding problem began in 2007, CalPERS liabilities have increased roughly 6 1/2 percent a year while assets increased about 3 1/2 percent a year, Terando said. But since the stock market crash, assets have been growing faster than liabilities the last eight to ten years.

After sinking to 61 percent the funding level has been increasing at the rate of about 1 percent year. Terando said CalPERS has tried to improve funding at a reasonable pace while keeping employer contribution rates affordable.

When the funding level was 61 percent, said Randall Dziubek, deputy chief actuary, the CalPERS discount rate was 7 3/4 percent and the estimates of expected life spans were well off the mark.

“So really we were not 61 percent funded,” said Dziubek. “We were probably 50 percent funded, if we knew then what we know now. So there really has been more of a recovery than what it looks like.”

Reporter Ed Mendel covered the Capitol in Sacramento for nearly three decades, most recently for the San Diego Union-Tribune. More stories are at Calpensions.com.