Californians will soon be allowed to eat roadkill but be prohibited from buying fur coats. Abortion pills will become available on college campuses, but tiny bottles of shampoo will be banned from hotel rooms. High school and middle school kids will get a later first bell, but schools won’t be forced to give kindergarteners a full-day program.

Democratic Gov. Gavin Newsom signed and vetoed the year’s final batch of legislation Sunday night, making decisions that will shape California in ways big and small. His choices during his first year as governor largely reflect Newsom’s progressive vision for the state. But they also offer a window into how he approaches his role as a leader — not only of California, but of the broader “resistance” movement opposed to Republican President Donald Trump.

Here are a few things Newsom revealed as he made his way through 1,042 bills the Legislature sent him this year.

He’s no Jerry Brown — and he wants you to know that.

Lawmakers frustrated by past vetoes saw fresh opportunity with a new governor and re-introduced many bills this year that Newsom’s Democratic predecessor had rejected. In most cases, Newsom obliged, signing numerous bills that amounted to do-overs from the past.

“Third time’s a charm,” quipped a cheerful Assemblyman Phil Ting as Newsom signed his bill expanding the use of gun restraining orders — something Brown had vetoed twice.

Other legislation Newsom signed that Brown had rejected: measures to make abortion pills available at college health clinics, allow child care workers to form unions, ban smoking on state beaches, make charter schools more transparent, start school later for sleep-deprived adolescents, and make it easier for victims of sexual harassment and child sex abuse to sue.

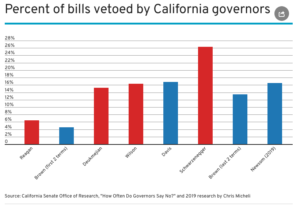

Other legislation Newsom signed that Brown had rejected: measures to make abortion pills available at college health clinics, allow child care workers to form unions, ban smoking on state beaches, make charter schools more transparent, start school later for sleep-deprived adolescents, and make it easier for victims of sexual harassment and child sex abuse to sue.Newsom’s decisions reflect a steady effort to distinguish himself from Brown, which began early in the year with a State of the State speech that signaled he would depart from his predecessor’s approach on water, education and housing. By the end of the year he had vetoed a higher proportion of bills than Brown did — 16.5% compared to 13.5% in Brown’s second stint as governor.

Newsom did agree with Brown on a few vetoes, however. In giving a thumbs down to AB 1451, Newsom became the third consecutive governor to veto a bill that sought to change the process for qualifying initiatives for the ballot by limiting the use of paid signature-gatherers.

He’ll seize any opportunity to bash Trump …

The high cost of rent for many Californians really doesn’t have anything to do with President Trump. It’s largely a supply-demand problem in regions where land values are high, employment is strong and housing production is low.

Yet Newsom managed to make dissing Trump a theme of his bill-signing ceremony at a senior center in Oakland where he enacted new laws protecting tenants from eviction and capping rent increases. He likened the president’s recent visit to California to “a seagull that comes in, and does what seagulls do, and flies away.”

Then he paused for comedic effect to let the seagull imagery sink in.

Newsom acknowledged that sky-high housing costs are a political vulnerability for California Democrats — and said Trump wasn’t wrong to highlight the state’s large homeless population.

“He’s exploiting it,” Newsom told housing activists at the bill signing ceremony. “You’re trying to solve it.”

It was one of countless times this year Newsom used his platform to criticize or make fun of Trump, and another example of how his style breaks from his predecessor. Brown limited his Trump-needling largely to climate policy, and engaged in fewer of the political tit-for-tats that Newsom seems to relish. It’s hardly a risky strategy in a state where two-thirds of adults disapprove of Trump, and has helped Newsom foster a national profile in his short time as governor.

… Even when he and Trump are on the same side.

Progressive Democrats sent Newsom a bill meant to counter Trump’s rollbacks of environmental regulations by enshrining Obama-era rules in California law. At first glance, it sounds like something Newsom would support as part of his broader anti-Trump agenda.

But the legislation got caught up in delicate negotiations over water, and in the end Newsom sided against environmentalists and progressive Democrats, and with farmers and the Trump administration.

Not that you’d know that from his veto message. Newsom reframed the debate, distancing himself from the president even as he took his side.

“No other state has fought harder to defeat Trump’s environmental policies,” Newsom wrote in his veto of SB 1. “And that will continue to be the case.”

He understands the power of image…

After vetoing the environmental bill on a Friday night — a classic politician move to bury unflattering news — Newsom followed up with an early Monday morning announcement orchestrated to attract national buzz. He released a video of himself signing a bill allowing college athletes to make money from sponsorships — on an HBO show with basketball star Lebron James.

“You the man Governor Gav!” James later wrote on Twitter.

On James’ Instagram, a video of the bill signing has been viewed more than 1.2 million times.

Newsom’s approach to signing the college sports bill took a page from former Gov. Arnold Schwarzenegger’s playbook. Aaron McLear, Schwarzenegger’s press secretary during his governorship, said the movie star governor saw bill-signing ceremonies as “a great opportunity to get out of Sacramento and speak directly to the public to demonstrate what their government is doing.”

… But he’s no entertainer, at least when it comes to veto messages.

Obscure historical references and snarky turns of phrase peppered Brown’s most lively veto messages. He complained of “enough mischief” and “mayhem” in nixing a bill to keep bars open later, bemoaned the “coercive power of government” in vetoing a ban on smoking on state beaches, and directed legislators to read a 50-year-old essay in the Federal Bar Journal in vetoing an anti-corruption bill.

The prose in Newsom’s veto messages was comparatively mundane. (“I am acutely aware of the need to address congestion and safety around Lombard Street. However, the pricing program proposed in this bill creates social equity issues,” he wrote, managing to find the prosaic even in a bill to charge tourists to visit the crookedest street in the world.)

But like Brown, Newsom also issued surprise vetoes, nixing some innocuous-seeming bills that had sailed through the Legislature, and even some of his own priorities.

For instance, though he promoted full-day kindergarten at the outset of his administration, he vetoed a measure that would have required schools, within three years, to add a full-day kinder program, citing fiscal concerns.

And not a single lawmaker voted “no” on measures requiring animal shelters to microchip dogs and cats, directing state technology officials to evaluate uses for artificial intelligence, and asking school districts to include apprenticeship programs at their college and career fairs. Yet Newsom vetoed all three.

“There’s reasons governors do things like that, because they have to pay attention to how it all gets implemented,” said Dana Williamson, a top aide to Gov. Brown. “A bill that the Legislature passes, even with no controversy, could have some operational impact on the state.”

His operation is still on a learning curve.

Newsom accomplished a lot in his first year as governor. He advanced policies that Democratic presidential candidates are just talking about — expanding health care coverage, closing private prisons and offering two years of community college without tuition for some students. He tackled long-simmering California challenges, getting dueling interest groups to agree on legislation to increase regulations on charter schools and limit when police can use deadly force.

But he stumbled, too. He sowed confusion with contradictory messages about his plans for high-speed rail. He garnered mistrust when he wavered on a bill to crack down on bogus medical exemptions from childhood vaccines — asking lawmakers to change the bill, and then, after they made the changes, taking to Twitter to demand more.

“Everyone in the Capitol was gasping, ‘What is going on?’” said Mike Madrid, a GOP consultant who was working for the doctor association that backed the vaccine bill.

“When you are dealing with the governor, or any executive office, you have to believe 100% that their word is their bond.”

Lawmakers were especially frustrated because the vaccine bill was so contentious, drawing hundreds of protesters to the Capitol for days on end — and culminating with a demonstrator throwing a menstrual cup of blood at senators on the final night of session.

Their sense of betrayal may have made it harder for Newsom to get what he wanted as the legislative year drew to a close. His fellow Democrats in the Legislature sent Newsom an environmental bill he opposed, and refused to take up a recycling bill that he wanted them to pass.

The snafus exposed shortcomings that the governor should try to address next year, Madrid said: “Being a governor, half of it is visioning and half of it is managing. On the visioning, he’s got an A-plus. On managing, there is room for improvement.”