Ninety-nine percent of all statistics only tell forty-nine percent of the story.” – Ron DeLegge, Financial Author

Having a high rate of economic growth solves a lot of problems. From government’s perspective, as businesses invest more and consumers spend more, there is ample tax revenue to fund ongoing priorities like education as well as short-term initiatives. There is extra revenue to pay down existing liabilities. And, with profitable businesses and higher employment, there is reduced strain on the budgets of social safety-net programs.

Gov. Gavin Newsom came into office wanting to achieve “big hairy audacious goals” in California, so it should come as no surprise that he touts the state’s high rate of economic growth whenever he can. In last month’s State of the State address, for example, Gov. Newsom proclaimed that California has averaged GDP growth of 3.8 percent over five years compared to 2.5 percent nationally. He summarized, “By any standard measure, by nearly every recognizable metric, the State of California is not just thriving but, in many instances, leading the country, inventing the future, and inspiring the nation.” This, just before elaborating on his extensive plan to solve homelessness in the state.

Of course, repeatedly emphasizing California’s economic growth sends the message that the state is so wealthy, it can absorb whatever burden is required to address the Governor’s extensive list of problems. Tax hikes? Sure. Cost increases? No problem. California is so wealthy, in fact, that business has no right to protest.

Gov. Newsom has essentially said as much: “For all the bitchin’ and complaining, I think businesses are doing pretty damn well.” He made these remarks last June at the Bay Area Council’s Pacific Summit while criticizing companies for focusing on California’s notoriously high cost of doing business. He added, “I see that CEO Magazine [lists California as the] ‘worst place in America to do business’ and yet our GDP growth outperforms every damn one of those other states they highlight…. Eat your heart out Texas, Tennessee — that’s always their top one and two.”

This, just three months before he signed the ill-conceived AB 5 into law, increasing further the cost of doing business in the state for both companies and independent contractors.

Despite California’s high costs, Gov. Newsom believes that its robust economic growth means that the state “is still the envy of the world.” But what if California’s economic growth is not as robust as he thinks? Or, more precisely, what if the statistics he cites provide an incomplete and misleading viewpoint?

It turns out there is less than meets the eye when it comes to the 3.8 percent average growth rate Gov. Newsom claims. This is clear from a deeper dive into the data, both historically and geographically.

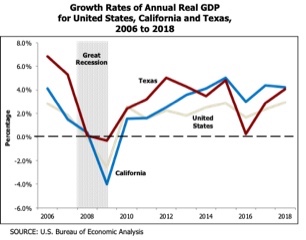

The chart below shows the growth rates of real annual GDP for the United States, California and Texas from 2006 through 2018 based on data from the U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis. Averaging real annual GDP growth for the six years spanning 2012 to 2017 does result in 3.8 percent growth for California, compared to 3.5 percent for Texas and 2.3 percent for the United States as a whole. But what is so special about the year 2012? As an economic milestone, absolutely nothing. The year 2010 holds more relevance for economic comparisons since it marks the end of the Great Recession and the start of the current business cycle. Even 2007 would be more informative, since measuring economic growth from this point would capture the Great Recession and indicate the resilience of the states to economic downturns.

The conclusions change substantially when using more appropriate starting points. Averaging annual growth rates of real GDP from 2010 to 2018 shows California with an average growth rate of 3.3 percent. While this exceeds the U.S. average growth rate of 2.3 percent, it falls below Texas’s average growth rate of 3.4 percent. When using 2007 as the starting point, California’s average growth rate drops to 2.3 percent. This compares to 1.6 percent for the United States and, shockingly, 3.0 percent for Texas.

To put this in perspective, Texas’s average GDP growth rate since 2007 is 30 percent larger than California’s. That’s 30 percent! Eat your heart out California?

There could be a number of reasons why Texas’s economy appears to be the stronger going back to the Great Recession. Perhaps it is due to a lower cost of living and a lower cost of doing business. Perhaps the Texas economy is more diverse. Perhaps the state has a stronger middle class. Whatever the reasons – and this piece is not intended to be an analysis of the underlying causes of Texas’s growth – Texas’s GDP has clearly outperformed California’s when using objective yard-posts.

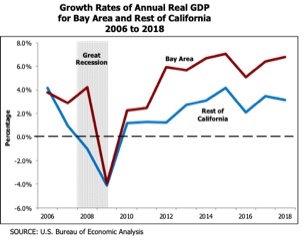

But the GDP data do suggest what is likely behind California’s economic growth numbers: Silicon Valley.

The chart below shows the growth rates of real annual GDP for California’s nine-county Bay Area region compared to the rest of the state. From 2012 to 2017 when statewide GDP growth averaged 3.8 percent, the Bay Area averaged an eye-popping 6.1 percent GDP growth while the rest of the state averaged only 2.8 percent. Since 2007 and 2010, the Bay Area GDP growth averaged 4.3 percent and 5.4 percent, respectively, exceeding the 1.5 percent and 2.5 percent growth rates for the rest of the state.

This divergence should not be entirely surprising. Anyone who was worked in or visited the Bay Area the past few years can attest that the regional economy is on fire. However, what is surprising is that absent the Bay Area, California’s economic performance actually resembles that of the United States as a whole. In other words, most of the state’s economy is solidly average.

California might still be the envy of the world, but it would be misleading to attribute this to California’s economic growth dominating that of its rivals. Texas shows that this just is not so. It would also be misguided to use California’s economic growth in and of itself as justification for imposing additional costly policies and tax hikes on the state. The Bay Area might have been able to handle the impacts relatively well – all bets are off until we learn more over the coming months about the magnitude of the economic dislocations caused by the coronavirus – but the Bay Area is not representative of the state.

It would seem instead that a bit of humility and caution from Sacramento might be in order when it comes to touting economic growth. After all, for all the bitchin’ and complaining, businesses might actually have a legitimate point.