In a March 26 article, The New York Times headlined: “Even before coronavirus, America’s population was growing at slowest rate since 1919.” Experts suggested that, with the coronavirus and falling immigration rates, the country could see a population decline next year.

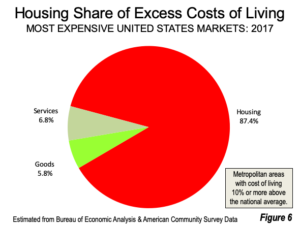

Lurking behind this overall assessment was even bigger news for Californians. Improbably, the much smaller Stockton, Fresno and Bakersfield metropolitan areas are now growing faster than the San Francisco and Los Angeles metropolitan areas, as well as the San Diego metropolitan area.

California’s five fastest growing metropolitan areas are all in the interior. Riverside-San Bernardino grew the fastest, adding 38,000 residents. This is equal to more than 75% of the state population growth total. Sacramento grew 22,000. Outside Riverside-San Bernardino and Sacramento, the state lost 9,000 residents. Some metropolitan areas gained population, but their gains were cancelled out by losses in other areas, especially Los Angeles.

Stockton, Fresno and Bakersfield were third, fourth and fifth in metropolitan area population growth. San Francisco was sixth fastest growing, adding fewer than 5,500 new residents. This is about one-seventh the growth of Riverside-San Bernardino and one-fourth that of Sacramento. San Francisco’s growth rate from 2018 to 2019 was only 0.12%, one-quarter of the anemic national rate (0.48%). On the other hand, Merced, recently added to the Bay Area combined statistical area, experienced the strongest metropolitan area growth, at 1.29%, nearly 11 times that of San Francisco (Figure 1).

Meanwhile, the Los Angeles metropolitan area remains in the growth doldrums. The population has declined for three years in a row. Net domestic out- migration continues to increase, up to 122,000 in 2018-2019. Over 100,000 came from Los Angeles County, which saw its net domestic migration loss double from 2013. The other Los Angeles metropolitan county, Orange, lost 21,000 net domestic migrants, compared to a gain of 2,000 in 2011.

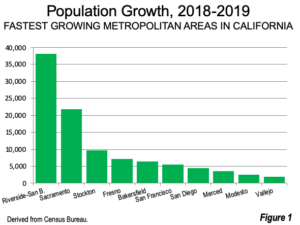

The annual population results are particularly sobering for the Bay Area. During the first half of the decade, the Bay Area experienced considerable population growth. However, in 2018-2019, the nine counties that abut the Pacific Ocean or San Francisco Bay (and which have long been considered to be the Bay Area) lost a combined 1,700 residents. By comparison, as commuters have been forced inland by exorbitant house prices, three counties have been added to the Bay Area combined statistical area. These counties, San Joaquin (Stockton), Stanislaus (Modesto) and Merced added almost 10 times as many new residents (15,700).

The contrast was even more stark in net domestic migration. The 9 counties that abut the coast or Bay lost 66,000 net domestic migrants, while the three added San Joaquin Valley counties gained 6,000 (Figure 2).

County Population Growth Analysis

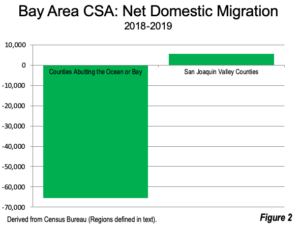

This analysis compares population data in the coastal metropolitan areas from Santa Rosa (in the Bay Area combined statistical area) to San Diego, with that of the interior counties, which are in the Sacramento combined statistical area, the San Joaquin Valley and interior Southern California (Riverside-San Bernardino and Imperial County). The balance of the state is the counties north of the Bay Area and Sacramento combined statistical areas and non-metropolitan area counties in the Sierra.

The combined population loss in the coastal metropolitan areas in 2018-2019 was 34,000. This compares to the interior metropolitan counties from Sacramento south, which experienced growth of 94,000 (Figure 3). The balance of the state lost 10,000 residents.

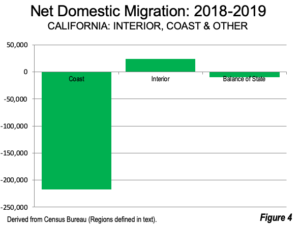

Not surprisingly, the interior dominated net domestic migration as it has since 2000. The interior gained 24,000 net domestic migrants. By comparison, the coastal metropolitan areas lost 218,000 net domestic migrants, in a single year (Figure 4). This means that for every 10 residents that leave move elsewhere in the United States from the coastal metropolitan areas, barely one in ten moves into the interior. This suggests a major problem for California as people are not opting as much as in the past to stay in the state.

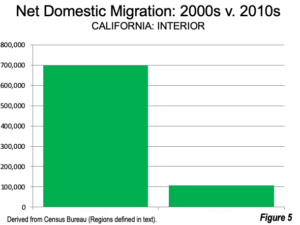

This can be seen by the fact that net domestic rate has plummeted, even in the interior, compared to previous generations. Between 2000 and 2009, the interior attracted 700,000 net domestic migrants. Between 2010 and 2019, the same area attracted only 106,000 net domestic migrants, a loss of 85% (Figure 5). Riverside-San Bernardino saw its net domestic migration gain from 2010 to 2019 (111,000) drop to less than one quarter than of the 2000 to 2009 gain (469,000).

California’s Success in Limiting Growth

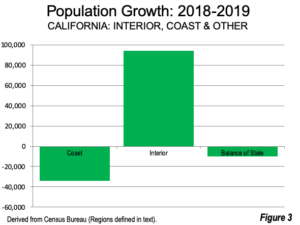

In recent decades, there has been considerable political support for limiting growth in California. As a result, overly restrictive land use regulations, especially urban containment regulation adopted in many areas and now imposed by state government. The resulting higher house prices have become a virtual “no-vacancy” sign in California, as most people who would like to move there cannot conceivably afford to.

And then, there is a ripple effect with respect to business relocations from elsewhere. The state is routinely rated as the worst in the nation for business by CEO Magazine, in large measure due to its unfriendly regulatory environment. California’s high cost of living, driven by its high housing costs. As Richard Florida has said, “differences in living costs are basically all about housing.” More than 85% of the difference in cost of living between metropolitan areas in the United States consists of housing costs (Figure 6). The high costs of living means that obtaining a competent work force presents an ever severe challenge for any company wishing to move to California. The latest Census Bureau estimates suggest that California will be stuck in a slow growth — perhaps even negative — mode unless the policy environment changes dramatically.