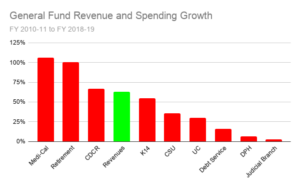

The California Department of Finance is in the process of preparing the May Revised Budget. A difficult process every year because of the state’s dependence on unpredictable capital gains taxes, this year DOF must also contend with a COVID-related revenue reduction. Absent reform, that bodes ill for discretionary programs that, even in good times, fare relatively poorly. See below for changes to expenditures over a recent period during which General Fund revenues grew at a healthy pace:

Now our state is faced with a decline in revenue that will pose extra risk to discretionary programs such as CSU, UC and the Judicial Branch. That’s because Medi-Cal is an entitlement, K-14 and Debt Service are constitutionally protected, Retirement Costs are contracts (though unlike normal contracts, pensions were raised retroactively in 1999 via legislation — retirement spending is up 700 percent since then), CDCR (Corrections) often operates under court order, and DPH (Public Health) will be favored this year. Just a 10 percent reduction in General Fund revenues could wipe out nearly 100 percent of funding for UC, CSU and the Judicial Branch, and while the state has a Rainy Day Fund, much of that money will likely be needed for increased spending on public health, Medi-Cal, and new health insurance subsidies enacted into law last year, plus school districts that were already laying off teachers before COVID are seeking relief from rising retirement costs.

Legislators will look for ways to protect discretionary spending but with 48 percent* of the General Fund constitutionally protected, entitlements like Medi-Cal (24 percent) hard to cut at any time and especially in a recession, and CDCR (10 percent) providing public safety services under court supervision, there isn’t much room. Retirement Costs (11 percent) provide no services, which sometimes leads officials facing budget pressures to employ dangerous tactics that pretend to reduce that spending (see e.g., Illinois) such as deferring retirement contributions, which is no different than borrowing money at a rate equal to the rate at which retirement obligations are discounted (7 percent in the case of California’s pensions), or issuing pension obligation bonds, which are nothing more than leveraged accounting maneuvers. The only legitimate way to reduce retirement spending is to reduce retirement obligations, which at $900 billion** in California are >10x larger than general obligation bond obligations that, unlike retirement obligations, were approved by voters. Legislators may also have an inclination to borrow, which if properly structured and transparently reported, can at times be reasonable.

Legislators will have tough choices to make.

*As of the last completed budget year (2018-19 fiscal year).

**Because retirement obligations are not legally defeased (i.e., offset) by retirement fund assets set aside to meet those obligations, it is erroneous to report (as many states do) only the “unfunded” obligations amount representing the difference between retirement obligations and assets set aside to meet those obligations. Employers are on the hook for the full amounts, which may be found in Comprehensive Annual Financial Reports.