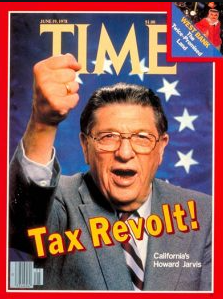

Although California turned a darker shade of blue on November 3, 2020, one victory for taxpayers came with the defeat of Proposition 15, a complicated, mundane, but ultimately very consequential measure on the California ballot.

Had Proposition 15 passed, it would have changed the way commercial properties are taxed, creating a “split-roll” tax by changing Proposition 13’s rules for assessing commercial and industrial properties while leaving intact the rules for assessing all residential properties and agricultural land. Proposition 13 is the landmark 1978 measure that capped property tax increases and has been a defining force in California fiscal policy ever since.

Liberal groups and public employee unions have been trying to roll back Proposition 13 protections for a couple of decades – unsuccessfully. If it had passed, the split-roll tax measure would produce $10 billion to 12 billion in new annual revenues for schools and community colleges, as well as for county, local and state governments.

Why Have Public Employee Unions Pushed so Hard for the Split-Roll Proposal?

In 2019 California Governor Gavin Newsom’s new administration in Sacramento negotiated pay raises with the state-worker public employee unions. Then the state was flush with revenues resulting from a booming economy and a former Governor (Jerry Brown) who had held the line on spending. Municipal governments followed the state’s lead and raised employee compensation across the board in many jurisdictions.

However, the COVID-induced recession has hit California especially hard in 2020. Newsom went from record state revenues and an $8 billion budget surplus to a $54 billion deficit in just three months. Local governments across California are facing billions in budget deficits as well. The COVID-19 pandemic has impacted every sector of the state’s economy and the Governor and Legislature hope for a federal bailout in order to avoid painful cuts.

But even before the recession, activists were making plans to put Proposition 15 on the ballot. Why the push for ever new taxes and revenues?

According to the California Department of Finance, the state has $256 billion in unfunded actuarial liabilities (UAL) and the gap is growing into a ticking time bomb. CalPERS also manages many municipal pensions that suffer from similar UALs. While most of the pay increases the Governor negotiated were in the three to five percent range, some classifications received as much as 25% in pay increases.

Most observers agree that the state needs to keep up with statewide compensation trends in order to attract and retain qualified workers. But continued failure to address unfunded actuarial liabilities (UAL) will cost taxpayers dearly in the end. As state and municipal worker salaries go up, so do future pension obligations.

The split-roll proposal was a politically safer way to go after higher taxes. Just two election cycles ago California levied the highest taxes in the country on the top one percent of taxpayers (13.3%). Going after the top one percent again has significant risks. The top one percent of taxpayers in this state contribute over 35% of the state general fund revenues, which totaled $146 billion before the recession. That means an extremely small sliver of people in this state, most of them in Santa Clara County (Silicon Valley) contribute over $51 billion of General Fund revenues.

California as a state is incredibly dependent on these uber wealthy – high tech – taxpayers whose income drops like a rock in a recession and stock market retrenchment. This is one reason why the split-roll proposal was on the ballot. While wealthy people can move, their commercial real estate holdings cannot. Commercial real estate assets are an easier target from which to extract funds.

Who Gets Impacted by Unfunded Pension Liabilities?

As the public employee pension UAL grows deeper and deeper, there are definite impacts on public services that taxpayers will increasingly feel. State employees face little risk that their pensions will not be paid in the future because the state’s promise to them not only is unconditional but also is senior in priority and secured by CalPERS’s assets. If CalPERS’s assets turn out to be insufficient—you guessed it—the California taxpayer is on the hook.

Furthermore, in the meantime, all of the consequences of rising pension costs fall on the budgets for programs such as higher education, health & human services, public safety, parks & recreation and environmental protection that are junior in funding priority and therefore have their budgets reduced whenever more money is needed to pay for pension costs. So, while taxpayers suffer from reduced public services and amenities, they will also have to fork over much more of their hard-earned money in the future to keep the state solvent.

What Can Be Done?

California lawmakers and the Governor cannot do anything about promises already made and pensions already earned. This means the state will be funding enormous liabilities for decades to come. Public employee unions and affiliated liberal allies will continue to seek higher tax revenues to fill the gap. We will see the split-roll proposal again at some point sooner rather than later.

There are alternatives to this bleak picture. California can hold the line on issuing unnecessary debt, it can increase annual contributions to the pension accounts, limit future salary increases, or refuse to issue pension obligation bonds. (The latter borrow long-term money to pay today’s obligations, temptingly providing short-term relief at the price of long-term fiscal malfeasance.)

California policymakers can also change pension fund governance in order to reflect taxpayer interests and to prohibit conflicts of interest like trying to achieve social change through pension investment policies like eliminating investments in oil and gas industries, guns or whatever the issue du jour is.

California needs to change pension rules and reduce the size of pension promises being made to new employees as well as compel them to contribute more of their own money in payroll deductions for retiree healthcare. None of these are politically easy; in fact, they will be incredibly difficult. California needs strong leadership particularly NOW while the economy is struggling with COVID recovery.

While the spirits of Howard Jarvis and Paul Gann (Proposition 13 authors) may be celebrating the failure of the split-roll assault on their beloved Proposition 13., let’s hope California gets a “V” shaped recovery and the fiscal hole is not as bad as it’s looking like it’s going to be. The next major shot across the bow comes in January when the Governor will unveil his 2021-22 budget and annual spending plan. While that proposal will likely be more of a placeholder until next May, it will give major signals as to how quickly we are likely to recover and what sort of revenues are expected to flow into state coffers.