As I’ve written about several times and Governor Newsom has telegraphed on multiple occasions that the state budget world has taken a 180. Monday, Assembly Budget Committee, chaired by Phil Ting (D-San Francisco, echoed the governor with a memo that brought many hopes and dreams to a screeching halt.

May Revision

- expects the Governor’s May Revision to become a “workload” budget that reflects 2019-20, or current, service levels

- “almost all new January 2020 budget proposals” would not be heard by budget subcommittees if they were to meet today

- the likely only new requests to be considered are COVID-19 related costs, wildfire prevention, and homelessness

- reductions to existing state programs may need to be considered

- deliberation on special fund programs, like those receiving Greenhouse Gas Reduction Funds will likely be deferred until after June 15

“August Revision”

- because of the delay of the personal income tax deadline from April 15 until July 15, a complete picture of revenues will likely not be available until August

- this will lead to a “second round” of budget deliberations, which will likely include additional spending demands related to the COVID-19 crisis

- at this time, “sizable ongoing reductions” may be required

- at this time, subcommittees will “not likely be able to revisit proposals for new investments”

Overall

“[W]e are in better shape to address the expected recession compared to any other point in the State’s history…While we may face one or more difficult fiscal years ahead, the prudent decisions we made since the Great Recession will help us avoid the lingering structural budget problems that plagued the State before 2012. We may have some difficult choices in the coming months, but we will be able to return to the stability, optimism, and innovation that characterized the State budget over the last eight years if we remain responsible.”

Here is your Assembly Budget Committee summary from January 10 when legislators, advocates, and would-be beneficiaries had twinkles in their eyes. The Legislative Analyst’s Office provided an analysis where the $6 billion in new discretionary spending was destined. Here are the big pieces:

- $1.6 billion for the state’s discretionary reserve, the Special Fund for Economic Uncertainties

- $2.6 billion in one-time spending, including $500 million in infrastructure-related construction and maintenance

- $1.6 billion in new ongoing spending

- $50 million in new tax breaks for small businesses

- $250 million in a supplemental payment to CalPERS, the state’s primary retirement system

Poof!

Generally, the one-time spending is attributed to above-projected revenues in the current year (2019-20), which stood at $1.25 billion through February, before the state’s economy largely shut down. Of the $1.6 billion in one-time funds, $750 million was proposed for homelessness-related spending. Of course, that current year surplus is almost certainly gone. Of the $1.25 through February, all of it was from above-projection personal income tax revenues. I need not tell you that all of that is likely gone. We won’t know state employment numbers for the month of March for another couple of weeks, but with all of the furloughs, layoffs, and postponement of the April tax deadline to July (which is a different fiscal year), we almost certainly have reversed from a current year surplus to a current year deficit.

Ordinarily, we would be just count on the state’s discretionary reserve, the Special Fund for Economic Uncertainty (SFEU), which was projected at $3.1 billion in January. However, much of that has already been tapped. The Legislature approved and the governor signed up to $1.1 billion in SB 89 on March, which is being used to secure housing for high-risk and COVID-19+ homeless individuals. That was appropriated out of the General Fund, which comes out of the SFEU. On March 25, the Governor tapped the SFEU for an additional $1.3 billion for response to the pandemic.

From my abacus, even if the January revenues were to materialize, that would drop the SFEU reserve to $700 million assuming no other emergency appropriations were made. That’s the “buffer” for lower revenues in the current year. So, add that to the $1.25 billion of above-projected revenue through February and the “available” cash as of the last report would be $1.95 billion, or about 2.2% of projected General Fund revenues for the 2019-20 fiscal year.

The economic impact of COVID-19 on the revenue side of the equation likely started in early March. While the statewide “Stay at Home” order was issued March 19, the Bay Area counties preceded it, and the news of the outbreak was already widespread. The markets started responding significantly on February 24, which accelerated after the oil price/production war began between Russia and Saudi Arabia on March 8. The President’s statement of “When you have 15 people, and the 15 within a couple of days is going to be down to close to zero. That’s a pretty good job we’ve done” was on February 26, forty-one days ago.

We almost certainly facing a precipitous drop in personal income tax (68%) and sales tax (21%) revenue, with the percentages reflecting the share of the state’s General Fund in 2019-20. These drops will show up for one-third of the state’s fiscal year, March-June. Starting with the $1.95 billion, discussed two paragraphs ago, we’re likely in the red in the current year my multi-billion dollars. Because of the delay in personal income tax deadline and allowance for small businesses to delay sales tax payments for up to twelve months, we won’t know exactly how far we’ve fallen for several months.

Forecasting 2020-21 revenues is impossible because (1) we don’t know when the current crisis will end, how much it will cost the state, and how far revenues will drop and (2) whether, if COVID-19 subsides over the summer, the virus makes a resurgence in the fall. I don’t envy the forecasters as, like this coronavirus, the fiscal situation is novel.

That doesn’t mean the state’s in an immediate fiscal crisis, although in “Budget Year Plus One” as Capitol folk call it (2021-22), we could be looking at significant budget cuts and/or revenue increases. The Legislative Analyst’s Office released a report Sunday on the reserves of the state and school districts. The experts write:

As of February 2020, the state has $17.5 billion in reserves. This includes $16.5 billion in the BSA and $900 million in the Safety Net reserves. (This excludes the Prop. 98 reserve , which I’ll discuss below.)

…

State Can Access “Amount Needed to Cover Emergency.” In the case of a fiscal emergency, the Legislature may only withdraw the lesser of: (1) the amount needed to maintain General Fund spending at the highest level of the past three enacted budget acts, or (2) 50 percent of the BSA balance. Hypothetically, if resources available for 2019‑20 were expected to be lower than the enacted budget for 2019‑20 by $5 billion, then the Legislature could access that amount from the BSA. If the amount of the budget emergency in 2019‑20 exceeded half of the reserve balance (currently, $7.8 billion) then the Legislature could only access that lower amount. In this situation, however, the state also likely would face a budget emergency for 2020‑21. In that case, the state could—in one budget cycle—use up to half of the BSA balance to address the current-year budget problem and still have the option to use the remaining balance to address the budget problem for 2020‑21 as well.

In short, we could wipe out three-fourths of the Budget Stabilization Account built over several years in the next eighteen months.

Moving on to Proposition 98, the minimum funding guarantee for K-12 schools and community colleges, where I’ve spent most of my career. Pursuant to Proposition 2, one-time Prop. 98 money was set aside for the funding under the guarantee for a rainy day. I’m guessing I don’t need to tell you that it’s pouring, or maybe hailing like it was at Nooner Global HQ on Sunday.

The LAO writes:

Compared with the BSA, the rules regarding deposits into the school reserve are more restrictive. Whereas the state has accumulated a significant balance in the BSA over the past several years, the state did not make its first deposit into the school reserve until it enacted the 2019‑20 budget plan. That deposit was $377 million—representing less than 1 percent of state spending on schools in 2019‑20.

Well, crap. But, don’t they have money under their couch cushions like the $1.10 in change I found under mine the other day in one of those moments of “I the news today, oh, boy…”?

Sort of. LAO:

How Much in Reserves Do Schools Hold? At the end of the 2018‑19 fiscal year, districts held a total of $12.8 billion in unrestricted reserves. This level represents 17 percent of district spending in that year—enough to cover about two months of expenditures. The data indicate that $6.9 billion of this amount was earmarked for specific uses and $5.9 billion was not earmarked. Some, but not all, of this funding would be available for schools to maintain a higher expenditure level if revenues declined. Many school districts would need to retain a significant portion of the reserves held in cash, for example, to continue to properly manage cash flow. Moreover, drawing upon earmarked reserves could involve foregoing various future projects or activities that districts regard as high priorities.

But…

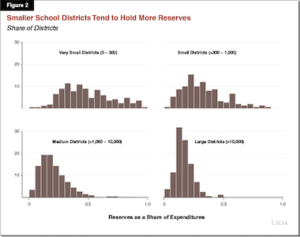

Reserve Levels Vary Widely by District. While district reserves average 17 percent of school spending statewide, significant variation exists at the district level. Figure 1 shows the variation in reserves as a share of expenditures. As the figure shows, the median district holds reserves equal to 22 percent of expenditures. At the lower end, about one-quarter of districts hold reserves equating to less than 14 percent of their expenditures. These districts likely would need to reduce spending quickly if their revenue were to decline. (Many districts, however, might find it difficult to reduce expenditures in a short time frame given their fixed costs and statutory requirements related to staff layoffs and the number of instructional days they must offer.) At the upper end, about one-quarter of districts hold reserves exceeding 35 percent of their expenditures. In these districts, the larger budget cushion could mitigate potential revenue reductions.

Note that unrestricted reserves do not necessarily include liabilities such as retiree health benefits or increases in pension contributions that may be forthcoming from CalSTRS and CalPERS if the funds’ investment returns lag over a sustained period of time.

And, it is the big school districts, some of which just went through strikes and otherwise contentious labor negotiations (incl. Sac City) that have the smallest margins:

Okay…deep breath.

Here are the LAO’s “key takeaways”:

- State Reserves at Historic Level, but Likely Lower Than Discussed in January.

Given economic decline due to the COVID-19 emergency, state revenues will be lower than estimated in January. Moreover, economic and budget conditions have evolved rapidly in recent weeks and are likely to continue to do so. Consequently, at this point, the most useful reference point for the state’s reserve level is the amount the state currently is holding in its reserve accounts—$17.5 billion. Compared to prior recessions, the state enters this period of economic uncertainty with significant reserves. That said, in the past, we have found that a budget problem associated with a typical recession could significantly exceed this sum. As such, the Legislature will want to consider carefully how to deploy these resources once more is known about the state revenue effects of this emergency.

- Local School District Reserves Could Provide Short-Term Buffer, but State-Level School Reserve Minimal.

Local school district reserves could provide many school districts with time to prepare for declines in revenues. Districts with larger reserves likely will have time to adjust their spending gradually, whereas districts with smaller reserves are likely to face difficult decisions more quickly. Regardless of their exact reserve level, however, few districts have enough to maintain current service levels for an extended period if revenues were to decline significantly. Moreover, the balance in the state-level school reserve is very small compared with the revenue declines schools might face. All of these factors suggest that state and school leaders should be very cautious as they prepare for the upcoming year.

Many of us have been here before and I’ve been through several rounds of budget cuts. Some readers including some of my former legislator friends and readers remember it all too well. However, we haven’t been more prepared in my 25 years here. Even after Prop. 13 in 1978, the state was flush with cash (one of the propelling factors of the ballot measure) and had to step up to save locals.

The bigger issue for legislators and Governor Newsom over the next couple of years than belt-tightening and cutting in Sacramento will likely be the solvency of many local governments and school districts. That’s a lot more complicated than coming up with inter-fund borrowing, deferrals, delayed pay, and other gimmicks of balancing the state budget that we did in the 1990s and through the first decade of the 2000s.