One little-recognized impact of this Great Recession is the hastening of California’s next retraining economy.

For years, even before the Recession, there was enormous movement, resembling Brownian motion, of California workers among jobs. In the 1990s and early 2000s when the economy was running well, and unemployment below 6%, the number of job turnovers, of hirings and separations, totaled over 40% of total employment per year in California, as elsewhere in the United States.

What has changed in the Recession is the shift from movement due to voluntary job changes (“quits” in Bureau of Labor Statistics terms) to movement due to job layoffs/discharges. Nationwide, the quit level, the measure of workers’ willingness to change jobs, was 1.8 million in September 2009, 43% lower than its peak in December 2006. At the same time, the discharge level for September 2009 was 2.1 million, 35% higher than its trough in January 2006.

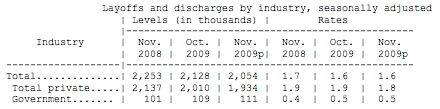

Below are the most recent layoffs/discharges data from the Bureau of Labor Statistics Job Openings and Labor Turnover Survey. Layoffs/discharges decreased from 2008 to 2009, but continued to be above voluntary quits (1.96 million in November 2009), a sharp reversal from most of the pre-Recession period.

The Recession has laid bare for California workers, as workers nationwide, the lack of security in most jobs and even most occupations. In doing, it has hastened a psychology of retraining, by which losing a job or occupation is regarded as part of the on-going economic change. Training is regarded as an enterprise to which workers come at several points in their work careers.

Further, the Recession has spurred the further development of a retraining structure in California. For some time, California has had a diverse retraining system, with the community colleges, California State University (CSU) system, adult education schools, community-based training agencies, and private proprietary schools. At little cost, especially through the community colleges, California workers could go back to school and learn new job skills, even new occupations.

And many did so. High school graduates took classes at night to improve skills and get advanced degrees. Laid off retail workers retrained as computer operators or registered nurses.

The Recession has meant cutbacks to the community colleges and especially to the CSUs. But it also has brought unprecedented funds to the public workforce system, at the center of which are the state Workforce Investment Board (WIB) and 50 local Workforce Investment Boards in California. The American Recovery and Reinvestment Act (ARRA) in 2009 brought $221.9 million in Dislocated Worker funds to California WIBs. This money was above the $212 million in Dislocated Worker funds that the WIBs were receiving in that year through the main federal workforce fund, the Workforce Investment Act.

Mr. Dennis Petrie (right) heads the Workforce Development branch at the state Employment Development Department (EDD), which oversees the Dislocated Worker funds coming to California.

Mr. Dennis Petrie (right) heads the Workforce Development branch at the state Employment Development Department (EDD), which oversees the Dislocated Worker funds coming to California.

Mr. Petrie notes that a good number of local WIBs in California have been slow in spending the Dislocated Worker surplus. This has not been due to any lack of training interest or capacity. Rather, it has been due to the lack of jobs to train for, in all quarters throughout the state. WIBs only want to train if specific job openings can be identified, or if job openings seem very likely in a particular sector. Today, and for the past year, the local WIBs, at best, have been able to identify the jobs in the tens in a particular sector in their region, not in the hundreds or thousands needed to keep up with all of the dislocated workers coming to them.

Mr. Petrie, though, is optimistic that once hiring begins to pick up in California, the retraining system will advance and even morph into a central part of the public workforce system. The retraining system started in the 1980s under the Job Training Partnership Act, the predecessor of WIA, was focused for many years on large-scale layoffs. The Dislocated Worker program of WIA continues to serve mass layoffs, but has developed to serving most workers laid-off in small-scale, even individual layoffs. The program is highly individualized, with the mix of placement services and training services tailored to the particular worker. The experience of the current Recession has pushed the WIBs to refine their retraining processes of skills and motivation evaluations and to identify the more effective training providers.

For some time, it has been recognized among California WIBs that in the future most workers not only will have multiple jobs in their worklives, but also multiple occupations and careers. The Recession is fast-forwardeding the psychology and structure of this future retraining economy.