A federal judge, who earlier ruled CalPERS pension contracts can be overturned in bankruptcy, yesterday outlined the difficulty of cutting pensions while approving Stockton’s plan to exit bankruptcy with pensions intact.

U.S. Bankruptcy Judge Christopher Klein issued a ruling on Oct.1 that CalPERS pensions, despite attempted safeguards in state law, can be cut in a municipal bankruptcy much like any other debt.

“Nobody should think that Chapter 9 (municipal bankruptcy) is an easy or inexpensive process,” Klein said yesterday, one of several remarks aimed at any thought that bankruptcy might be a painless way out of financial problems.

Judge Klein said some press reports of his earlier ruling did not pick up the “triangular arrangement” of the Stockton pension contracts, which was described in briefs submitted by the retiree committee and other parties.

“We have a triangle of bilateral relations in the law,” he said.

The contract between the city and its employees for pay and pensions is “the basic pension contract.” A second contract is between the city and CalPERS, which is the one the judge ruled can be rejected.

Another leg of the triangle is the relationship between CalPERS and the city employees, who are “third-party beneficiaries” under the law with rights enforceable as contracts.

To cut pensions, said the judge, the city would have to reject its contract with CalPERS and “more importantly” its contract with employees. Pensions are part of total pay, and while in bankruptcy Stockton negotiated contracts with unions.

Klein said employees agreed to pay cuts during the negotiations with the understanding that pensions would not be cut. He said all of the concessions were “made on the direct income side not the pension side.”

So to cut pensions, the city would have to reject a collective bargaining agreement. A U.S. Supreme Court decision (Bildisco 1984) set a higher standard for rejecting a collective bargaining agreement.

The judge said Congress responded by setting a higher standard than Bildisco for rejecting a collective bargaining agreement in business bankruptcies (Chapter 11), which so far is not applicable to municipal bankruptcies.

He said rejecting a “garden variety” contract is a low-level hurdle, rejecting a collective bargaining agreement under Bildisco is a higher hurdle, and rejecting a bargaining agreement in a business bankruptcy is an even higher hurdle.

“So it would be no simple task to go back and redo the pensions,” said Klein. In the case of Stockton, the package of pay concessions would have to be reopened, which “as a practical matter would be difficult to do.”

The judge did not directly discuss an issue he has mentioned in the past: Whether the Stockton restructuring and debt-cutting plan will keep the city out of the red and avoid a second bankruptcy.

A credit-rating agency, Moody’s, said last February that Stockton and San Bernardino, another bankrupt city, are at risk of returning to insolvency if they do not get relief from rising pension costs.

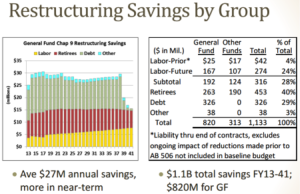

Some points of the Stockton plan mentioned by the judge: Voter approval of a ¾-cent sales tax, pay cuts that result in lower pensions, the elimination of retiree health care and removing debt payments from the deficit-ridden general fund.

“This plan, I am persuaded, is the best that can be done in terms of the restructuring and adjustment of debts of the city of Stockton,” Klein said.

Agreements with creditors approved by Stockton City Council last April

Agreements with creditors approved by Stockton City Council last April

Stockton does not want to cut pensions, arguing they are needed to be competitive in the job market, particularly for police. City officials warned that a pension cut would cause a “mass exodus” of employees.

But a lone holdout creditor, two Franklin bond funds owed $36 million, raised the pension issue by arguing that the Stockton exit plan gave Franklin a penny on the dollar while making no cut in the city’s largest debt, pensions.

A federal judge in the Detroit bankruptcy ruled last fall that pensions can be cut in bankruptcy. CalPERS joined in an appeal of the ruling, arguing among other things that it operates as an “arm of the state” and is protected in municipal bankruptcies.

Klein said his Oct. 1 ruling “undermines what heretofore had been assumed to be an important assurance of pensions.” The ruling is not a binding precedent, but it will be read by other judges and, some think, may give cities bargaining leverage with unions.

Klein ruled that two CalPERS-sponsored state laws are invalid in a federal bankruptcy. One prevents a city from rejecting a CalPERS contract in bankruptcy. The other places a CalPERS lien on all assets, except wages, when a city declares insolvency.

When a city contract with CalPERS is terminated, the big retirement system imposes a fee, based on a low earnings forecast, that is large enough to cover all of the future pension obligations.

The termination fee for Stockton is $1.6 billion, large enough to make leaving CalPERS financially difficult if not impossible. Klein suggested that the termination fee could be adjusted in bankruptcy, much like any other debt.

Although some have said CalPERS is Stockton’s largest creditor, the judge said CalPERS is only owed the cost of administering the pensions. The pension debt is owed to employees and retirees.

“They are, as I have said on several occasions, the real victims of any (debt) adjustments,” he said.

The CalPERS general counsel, Matthew Jacobs, told reporters the approval of Stockton’s plan that leaves pensions intact makes the earlier ruling “less significant.” He said CalPERS is looking at its options, including the possibility of an appeal.

Klein said the city’s debt-cutting “plan of adjustment,” approved yesterday, pays 12 percent of the Franklin debt, not a penny on the dollar. He said the plan pays Franklin $4 million for its collateral, two golf courses and a park.

Franklin objected to being placed in the same class of creditors as retirees, who voted to accept a $5 million lump sum for a long-term retiree health care debt of $545 million. The big retiree vote approved a similar debt cut for all creditors in the class.

“Obviously, we are disappointed by your ruling,” James Johnston, a Franklin attorney, told the judge after the Stockton plan was confirmed. “We will evaluate our next steps.”

Johnston said Franklin does not think the city has met the requirement for fully disclosing bankruptcy fees. Last June the city reported $13.9 million in fees, including $10.4 million to the law firm of Orrick, Herrington and Sutcliffe.

Marc Levinson, an Orrick attorney for Stockton, told reporters the city hopes to be out of bankruptcy by the end of the year. Stockton filed for bankruptcy on June 28, 2012.

Cross-posted at Calpensions.