Legalizing marijuana, California voters were told last year, would create a “safe, legal and comprehensive system” allowing adults to consume the drug while keeping it out of the hands of children. Marijuana would be sold in highly regulated stores, the Proposition 64 campaign promised, and California would gain new tax revenue by bringing the cannabis marketplace “out into the open.”

Voters overwhelmingly bought the message, with 57 percent approving Proposition 64. But as state regulators prepare to begin offering licenses to marijuana businesses on Jan. 1, it turns out that a huge portion of the state’s weed is likely to remain on the black market.

That’s because California grows a lot more pot than its residents consume, and Prop. 64 only makes marijuana legal within the state’s borders. It also didn’t give an automatic seal of approval to every cannabis grower. Those who want to sell legally must be licensed by the state and comply with detailed rules that require testing plants, labeling packages and tracking marijuana as it moves from farm to bong.

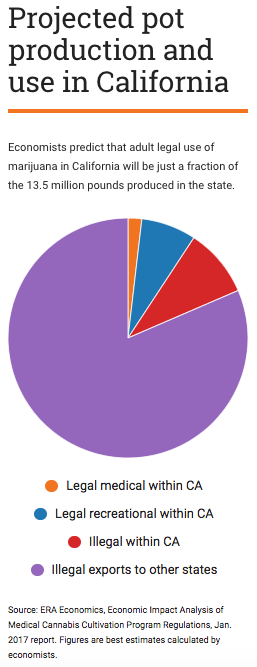

Exactly how much cannabis circulates in California is unknown because most marijuana grows—and purchases—have been illegal for so long. But economists hired by the state government estimate that California farms produce about 13.5 million pounds of cannabis each year, while state residents annually consume about 2.5 million pounds. That leaves 11 million pounds of pot that likely flows out of California illegally, according to the economic report commissioned by the California Department of Food and Agriculture, which regulates cannabis farmers. Other analyses have similarly found that roughly 80 percent of California-grown marijuana leaves the state.

Even the 2.5 million pounds of marijuana consumed within California won’t all be purchased through state-sanctioned shops when they open; the economists predict about half of it will probably be sold illegally.

“Those sales opportunities will still be there,” said Hezekiah Allen, executive director of the California Growers Association, which represents more than 1,000 marijuana businesses in the state.

Allen surveyed his members recently and found that 85 percent hope to get a license to sell marijuana legally under Prop. 64. But many fear they won’t be able to because some local governments will limit or ban pot businesses, or because prices could drop too low in the regulated market. And if they can’t sell weed legally, 40 percent of the respondents to Allen’s survey said they would continue operating the way they always have: on the black market.

Some long-time cannabis growers will likely go out of business, Allen said. But, “at the end of the day, a lot of businesses in general may stay outside of the regulated market.”

That means that despite the passage of Prop. 64, California cops will still have plenty of work going after illicit cannabis operations.

“You’re going to see robust enforcement efforts to prevent California from becoming the staging area for drug trafficking nationwide,” said John Lovell, a lobbyist for the California Narcotics Officers Association, which opposed the ballot measure.

A spokesman for the Prop. 64 campaign said the measure wasn’t intended to abolish all criminalization of marijuana but instead to allow opportunities for “operators who want to be responsible and compliant.”

“No one ever promised to completely eliminate the black market—that’s like promising security cameras will completely eliminate shoplifting—but it will be significantly reduced,” spokesman Jason Kinney said by email.

He added that the state’s estimates of marijuana supply and demand are unreliable because the legal marketplace created by Prop. 64 won’t begin to roll out until next year. And he pointed out that some of the tax dollars generated by legal marijuana sales will go toward cracking down on illicit operations.

State officials said they are encouraging marijuana businesses to follow the rules and become part of the regulated system, while also planning how to go after those that remain in the black market.

“We are developing a formal complaint system that will allow anyone to report illegal grows or other concerns, and then we will forward those potential issues to the appropriate (law enforcement) agencies,” said Rebecca Forée, a spokeswoman for the state’s cannabis cultivation licensing office within the Department of Food and Agriculture.

Lori Ajax, chief of the state’s Bureau of Cannabis Control, said her agency is trying to entice marijuana businesses to go legit by crafting rules that aren’t too difficult for them to live by.

“It’s making sure those people who want to be in the regulated market, that we have made a path for them, we’re not making our regulations so difficult and hard to comply with that you’re discouraging people,” Ajax said.

“First, we’ve got to get those folks in there and… then see what comes after that with enforcement.”